The brutality with which Negroes are treated in this country simply cannot be overstated, however unwilling white men may be to hear it.

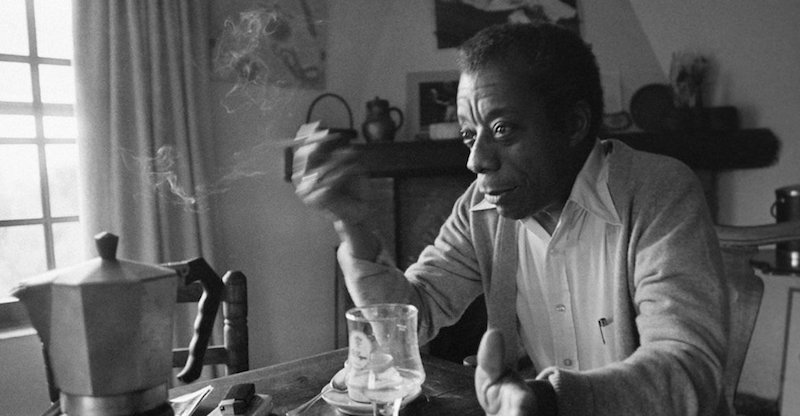

“‘You must put yourself in the skin of a black man. . .’ writes James Baldwin as he seeks to translate what it means to be a Negro in white America so that a white man can understand it.

Despite the inherent difficulties of such a task, his translation in his latest book, The Fire Next Time, is masterful. No matter the skill of the writer, and Mr. Baldwin is skillful, one can never really know the corrosion of hate, the taste of fear or the misery of humiliation unless one has lived it. Only James Meredith knows what it really means to be James Meredith. But if the actuality cannot be known, it can be related.

On one level it can be related so the listener becomes more or less curious, mildly interested and intellectually aware of what he is hearing.

On another and higher level, it can be related so the listener becomes virtually part of the experience, intensely feels the hurt and pain and despair, and yes, even the hope. The listener can be transformed, as far as words will take him, into the skin or the teller. Out of his own pain and despair and hope, Mr. Baldwin has fashioned such a transformation.

He has pictured white America as seen through the eyes of a Negro.

What he has drawn will not sit well with even some whites who count themselves as friends of the Negro. But he has not written this book of two essays to please.

‘The brutality with which Negroes are treated in this country simply cannot be overstated, however unwilling white men may be to hear it,’ he writes.

Thus he has written from a heart which has felt a unique kind of hurt and a brain which has desperately sought hope in face of what often seems to be the merciless logic of despair. He has fashioned his plea to America out of the past he has know, from the ferment of the present and the possibilities of the future.

“Mr. Baldwin pleads: ‘If we—and I mean the relatively conscious whites and the relatively conscious black, who must, like lovers, insist on, or create, the consciousness of others—do not falter in our duty now, we may be able, handful that we are, to end the racial nightmare, and achieve our country, and change the history of the world.’

Otherwise, the next time fire.

He opens the longer essay with the story of his experiences as a youth in Harlem when he ‘fled into the church’ out of the despair of his existence. His heart guides his pen. His experience tells the tale in staccato clarity.

He wonders why God ‘if His love was so great, and if He loved all His children, why were we, the blacks cast down so far?’

He says, switching from visceral to intellectual inspiration, that Christianity has operated with ‘unmitigated arrogance and cruelty.’ He writes of the ‘remarkable arrogance that assumed that the ways and morals of others were inferior to those of the Christians. . .’

But if the facts he adduces are damning, his transcendent hope remains. He says we must not ask whether it is possible for a human being to come truly moral.

‘I think we must believe it is possible,’ he writes.

Mr. Baldwin is proud of his race, of those who have been able to ‘produce children of kindergarten age who can walk through mobs to get to school.’ He says the ‘Negro boys and girls who are facing mobs today come out of a long line improbable aristocrats—the only genuine aristocrats this country has produced.’

And again, torn between reality and hope, he pleads for Americans to reject the delusion of the value placed in the color of skin. He admits what ‘I am asking is impossible,’ but adds that human history, and American Negro history in particular, testifies to the perpetual achievement of the impossible.

He has sounded a warning and a hope. Men of good will must hope his hope is well founded.”

–Sheldon Binn, The New York Times, January 31, 1963