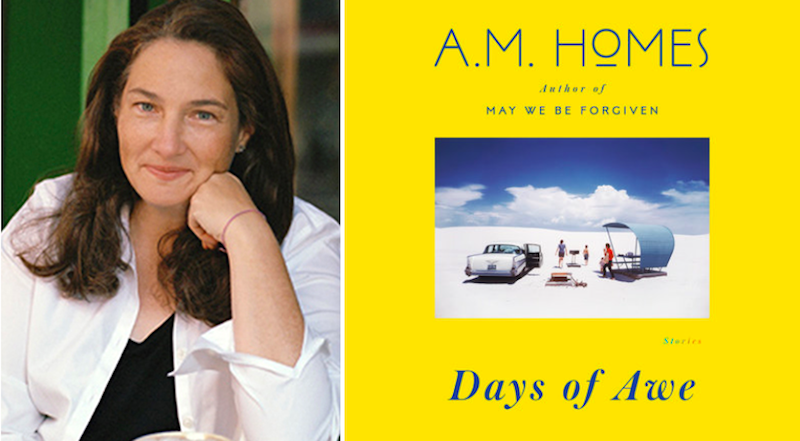

A.M. Homes’ new short story collection, Days of Awe, is published this month. We asked her about five collections that have shaped her writing life.

*

Raymond Carver, What We Talk About When We Talk About Love

Jane Ciabattari: What’s the first story collection that made you want to write stories?

A.M. Homes: Raymond Carver’s What We Talk About When We Talk About Love, and Harold Brodkey First Love and Other Sorrows and Richard Yates’ 11 Kinds of Loneliness. I would say these three were my “formative” triad.

JC: Why did you put Carver first?

AMH: Carver does something very unusual; he uses regular words in the regular order and yet somehow when he writes, the words create a vapor—a kind of mystical cloud, somewhere between invisible and candy floss. The cloud has shape and definition, but when you put your hand through it—nothing.

I imagine rolling up a shirt sleeve and, like a scientist, putting my arm into this cloud that hovers above the words and then extracting it only to find a kind of magical dew on the hairs of my arm.

Part of what fascinated me about Carver early on was reading two versions of one short story. I didn’t know it then but there was “The Bath,” as edited by Gordon Lish and “A Small Good Thing,” apparently Carver’s preferred version. Both are the story of a boy who on his birthday is hit by a car on his way home from school (something which did happen to a friend of mine’s son and so made it all the more palpable). In one version (“The Bath”), the baker who baked the uncollected birthday cake calls the parents harassing them about paying for the cake, and in the other the baker apologizes and feeds the parents rolls and coffee and cares for them. So one version is rather brutal and the other much more sentimental/human. The idea that a story could have two such different versions—two very different effects—stunned me. Only as I learned more about the art of revision and working with an editor did this make sense. First knowing and then having experienced being edited by Gordon Lish, who was Carver’s editor and who once edited a story of mine so rigorously that it was unrecognizable, I now have a deeper understanding of how transformative editing can be—but as a young writer it felt disconcerting. I still remember what Gordon Lish wrote to my agent when accepting my short story for his magazine, The Quarterly. “Is this the same A.M. Homes who was a student of mine? If so, my oh my, what a good teacher am I.”

JC: And what is it that impressed you about Brodkey and Yates?

AMH: There is a tenderness and vulnerability to both Brodkey and Yates that is mixed with a kind of intensity, an anger or resentment towards the lives of others, which they perceived as more successful or easier. I also loved Brodkey because he articulated the splits in his identity—as an adopted child, as someone whose sexuality shifted.

John Cheever, Collected Stories

JC: Which story collection do you reread the most?

AMH: John Cheever, Collected Stories. I own multiple copies—at this point I think I re-read it to somehow check myself, like getting an annual physical. I can tell how I am by revisiting Cheever.

JC: Is there a particular story that means the most to you? (I find myself returning to “The Enormous Radio,” and marveling at how Cheever was so far ahead of his time.)

AMH: “O Youth And Beauty,” published August 22, 1953 in The New Yorker. For me this is classic Cheever: a man obsessed by his virility, by his power, and in an attempt to recreate a hurdle race over the furniture, he’s accidentally shot dead when his wife, who knows nothing about guns, fires off the starting shot, catching him-mid air. (It may not actually be mid-air, but that’s how I like to remember it.)

Joyce Carol Oates, Where Are You Going, Where Have You Been?

JC: Which collection still stays with you years after first reading?

AMH: Joyce Carol Oates’ Where Are You Going, Where Have You Been? She is inescapably terrifying—J.C.O. talks about what we fear the most, in a deeply human, plainspoken way that you might not realize you’ve been bonked on the head with a hammer until a day, a year, or years later. She is entirely unafraid of the full range of human behavior—especially the most grotesque parts.

JC: She drew the title story from a real-life serial murderer in Tucson. Is that what inspired you to dip into the news for inspiration for your novels and stories? (Including, in your new collection, Omega Point, a fabulist tale that draws upon real-life characters Lue Gim Gong, the Citrus Wizard; Pierre Teilhard de Chardin and Vermonter Walter Grange, discoverers of the bones of Peking Man?)

AMH: I love the way Joyce has often taken real life as a starting point—but I think for me that combination also comes from the work of Don DeLillo, Joan Didion and then also Norman Mailer. I avoided reading Mailer for many years, having grown up aware of him less as a writer and more as a strong personality who battled with Grace Paley and Susan Sontag. So only recently have I begun to read his work and find myself pleasantly surprised. But it’s really DeLillo and Didion whose work with history has inspired me. In White Noise, DeLillo’s character Jack Galadney is a professor of Hitler Studies in North America—between that and the Toxic Event, and of course Libra and Underworld, DeLillo gave me the creative freedom to write Harold Silver, a Nixon Scholar, and then also to dip into the blend of philosophy, world history and “local” history that created “Omega Point Or Happy Birthday Baby” (as it was originally called—we shortened the title for the collection). (Point Omega is also the title of a DeLillo book—so the story also is a play on that.)

Joyce Carol Oates, High Lonesome: Selected Stories, 1966-2006

AMH: Another J.C.O. I imagine her as someone who can look at road kill and tell us exactly what happened—what kind of car, who was driving, what their mood was and how taken by surprise they were by what jumped out of the dark. She is like a detective of the soul.

JC: Do you have favorites in this collection—especially from her most recent stories? How would you say her work has shifted over time?

AMH: In terms of Joyce’s work, I would say that while it has remained consistent in her willingness to go unblinkingly into the dark, it’s also gotten more intimate, more personal over the years. As much as I like her fiction, I also love her memoir(s). Basically I’m so in awe of her both as a writer and a person that I want to learn more about how her mind works. She was among my colleagues at Princeton and when we had faculty meetings I was always amazed by how well, how deeply she remembered every student. Years after they’d been in her class, she could recall what they wrote about, how willing they were to take suggestions. It was remarkable. She is also very generous, with her time, with her willingness to participate in the larger life of the community.

Jayne Anne Philips, Black Tickets

JC: Which collection opened doors to your own future as a writer?

AMH: Black Tickets was published in 1979, the year I graduated high school. A Seymour Lawrence Book—that was something special. Lawrence was also Richard Yates’ editor. The work was dark, mysterious, sexy, dangerous stuff by a woman writer just a few years older than me, from West Virginia, a place not so far from Washington, D.C., where my family lived. I spent time in West Virginia with my grandparents, I knew the depth of the history, the elusive emotional swamp bog of place. Her writing was exciting, somewhere between theatre and poetry, and it meant that something was possible.

JC: In an early review, John Irving called Black Tickets “a sweetheart of a book,” and praised sentences like this one, from the title story: “The morning before I never saw you again, I opened my eyes and your shorn hair was all over my naked front. You had cut it to a jagged bowl around dawn, standing over me with scissors and scattering the pieces.” What was your favorite line/story?

AMH: The opening line of the title story, “Black Tickets”: “Jamica Delila, how I want you; your clean yeast smell, a high white yogurt of the soul.” That story to me is so stunning, filled with roughness and sexuality; a girl coming into her own, an abusive man. Philips writes fiction with the language of poetry, there are gaps and skips and the kinds of things that an English teacher would shake her head, no, no, no to. But that no, no, no sounds to me, not like a rebuke, but like a rhythm section and I say, yes, yes, yes, like a sizzling cymbal.

If you buy books linked on our site, Lit Hub may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.