It’s fear that makes us lose our conscience. It’s also what transforms us into cowards.

*

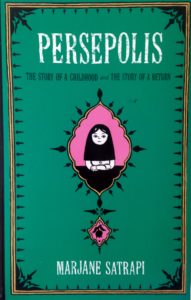

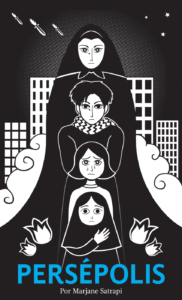

“The two volumes of Persepolis, the implacably witty and fearless ‘graphic memoir’ of the Iranian illustrator Marjane Satrapi, relate through an inseparable fusion of cartoon images and verbal narrative the story of a privileged young girl’s childhood experience of Iran’s revolution of 1979, its eight-year war with Iraq, her exile to Austria during her high school years, and her subsequent experience as a university student, young artist, and wife in Tehran after her return to Iran from Europe in 1998. That Persepolis 1, a book in which it is almost impossible to find an image distinguished enough to consider an independent piece of visual art, and equally difficult to find a sentence which in itself surpasses the serviceable, emerges as a work so fresh, absorbing, and memorable is an extraordinary achievement.

In the cartoon world she creates, pictures function less as illustration than as records of action, a kind of visual journalism. On the other hand, dialogue and description, changing unpredictably in visual style and placement on the page within its balloons, advance frame by frame like the verbal equivalent of a movie. Either element would be quite useless without the other; like a pair of dancing partners, Satrapi’s text and images comment on each other, enhance each other, challenge, question, and reveal each other. It is not too fanciful to say that Satrapi, reading from right to left in her native Farsi, and from left to right in French, the language of her education, in which she wrote Persepolis, has found the precise medium to explore her double cultural heritage.

“Satrapi herself has said in an interview, ‘There were many things I didn’t do because I couldn’t do them. But I was clever enough to take my lack and make a style of it.’ It is precisely this quality of inventive limitation, the visible struggle with the accidents of restriction, of fruitful disillusionment, that makes Persepolis such a winning, rueful, and effective autobiography, the story of the creation of a person, of a way of being in the world, partly shaped by heritage, partly at odds with it.

Persepolis renders human actions, ideas, and feelings as having the vitality, quality of apprenticeship, and crudity of cartoons. As cartoons, we see the world in what we do not recognize is our own style, confined in frames we are unaware of; gods, rulers, and lovers appear to us, at least in part, as our own creations. Persepolis, with its narrow range of styl-ized cartoon gestures and expressions, obliquely makes the orthodoxies Satrapi encounters—the ‘divinely chosen’ monarchy of the Shah, as Iranian schoolbooks of the period declared, the Islamic theocracy that replaces him, the smugly xenophobic Catholicism she confronts in her Austrian school years—seem presumptuous. How can creatures pretend to know God with such detail and confidence when they are still in search of their own characters, when they can know so little of themselves?

“It is not toward the idea of God that Satrapi is irreverent; it is toward a too credulous approach to the ambiguities of human motives and the temptations of moral aspiration. She sees how religious faith may serve as an exemption or protection from the discipline of self-knowledge, can function as a way of freeing a person from the work of moral inquiry, and create an environment in which a person’s will and desires are so identified with the divine that he feels anything is permitted to him. Satrapi is the moral equivalent of an insomniac; she allows herself no moral repose. In a powerful and funny moment, after a conversation with her mother about the need to forgive people who had done harm in the service of the previous regime, Satrapi draws herself making speeches about forgiveness to a mirror, rapt in the image of her own invincible goodness. Satrapi may very well be a believer in God; it is above all toward herself that she is an agnostic.

…

“In Satrapi’s work, there are equalities so powerful that they transcend the proscriptions of social convention, age, sex, nationality, the will of law and theology itself. One of these is the shared capacity for cruelty. Another is human vulnerability, brought home to the young Marjane when two of her parents’ friends, released from the Shah’s prisons, in the unguarded joy of their reunion describe the tortures the prisoners suffered, including being burned by heated irons.

“Her style in Volume 1 is faintly reminiscent of Bemelmans’ in his Madeline books, though the figure of benevolent nun Miss Clavel is transformed into grimly authoritarian chador-wearing schoolteachers and morals patrol squads. Bemelmans’ little Parisian girls are dressed in uniforms because they are being well brought up and protected, while the costumes of the little girls in Persepolis have become a matter of life and death. Both Satrapi and Bemelmans draw the world as toylike, with a deliberate, stylized childish charm; their figures, both adults and children, are doll-like, though in each, the figures of children are more poignant and alive, because they are drawn like toys come to life, their miniature bodies animated by passionate gestures and postures, by a full-scale emotional life they are as yet safely powerless to live. In Bemelmans, and in many other children’s book illustrators, this style promises that wishes are granted, that experience is a form of play, that the characters will not come to any real harm, whatever their adventures. Satrapi uses this style, which offers a benevolent, trustworthy world, like a fresco in a nursery, and matter-of-factly breaks our hearts with it, creating a confrontation between what is drawn as adorable with a world that does not requite its claims to protection, hope, or love.

“In Satrapi’s Iran, one is forbidden to be truly and fully Iranian. Eventually, ‘not having been able to build anything in my own country,’ she emigrates permanently to France. That sense of failure constitutes the only falsehood in a resolutely honest pair of books. Satrapi has surely built something both inside and outside her country with Persepolis. She communicates both the richness and self-destructiveness of Iranian culture. The double life Iran has forced on her has made her neither a cynic nor an idealist, neither an atheist nor a fanatic. No Molly Bloom, she says both no to the world and yes, with the shifting proportions of dissent and assent of a genuine artist.”

–Patricia Storace, The New York Review of Books, April 7, 2005