This week marks the 76th anniversary of the disappearance of French writer, journalist, and aviator Antoine de Saint-Exupéry. On July 31, 1944, Saint-Exupéry took off in an unarmed P-38 on his ninth reconnaissance mission for the Free French Air Force from an airbase on Corsica, and never returned.

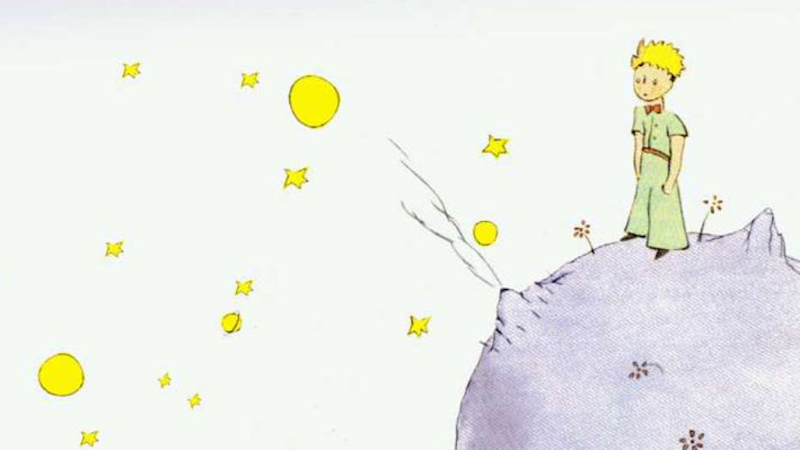

His most famous work, The Little Prince, tells the story of an aviator, downed in the desert and facing long odds of survival (inspired by the author’s own experience crash landing in the Libyan desert in 1935), who encounters a strange young prince, fallen to earth from a tiny asteroid where he lived alone with a single rose. The rose has made him so miserable that, in torment, he has taken advantage of a flock of birds to convey him to other planets.

As Barry James in The New York Times wrote: “A children’s fable for adults, The Little Prince was in fact an allegory of Saint-Exupéry’s own life—his search for childhood certainties and interior peace, his mysticism, his belief in human courage and brotherhood, and his deep love for his wife Consuelo but also an allusion to the tortured nature of their relationship.”

We take a look back at some of the earliest reviews of Katherine Woods’ 1943 English language translation of this beloved and deceptively profound novella.

*

And now here is my secret, a very simple secret:

It is only with the heart that one can see rightly; what is essential is invisible to the eye.

*

“There is a verse in the New Testament which is often quoted but never taken seriously. Had it been we would not today be tearing the planet and its civilization to bits. That verse in the 18th Chapter of Matthew tells us that except we become as children we cannot enter the Kingdom. And I hope I give no offense in this connection if I say that the text may be applied to literature. For I think that much of the wisest literature is that which seems written for children—stories of Aesop and Hans Christian Andersen, for example. And please consider those sentences my review of a beautiful book written and illustrated by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, The Little Prince (Reynal & Hitchcock: $2). For here is a sweetly and simply told tale of a little boy from a very little asteroid, so big with meaning that even important people will find wisdom in it; so simply told that even critics and college professors ought to understand its beauty and meaning; a thin little book filled with rich substance; something easy to read and remember and hard to forget.”

–Paul Jordan-Smith, The Los Angeles Times, 1943

*

“The door’s wide open on my guess as to how this will sell. It may get a break, it may be read by the right people, those rare adults who can go over the border of the Never Never Land without a backward look, who can sense intuitively that intangible outer fringe of unreality that is wholly real to children. Let’s say that those who loved the fey quality in Barrie—in Robert Nathan—who read their Alice for sheer escape rather than self conscious nostalgia, they will touch the gossamer beauty of The Little Prince, and chuckle over it, and take it as simply and unaffectedly as ‘St Ex’ himself. Perhaps belief in ‘the little prince’ is the forerunner of belief in the gremlins; who knows? This is a fairy tale for grown ups; later the children will claim it, I am sure. It is the tale of the tiny creature who came to Saint-Exupery when he was stranded in the Sahara, who told him the saga of his exotic travels in search of truth, when he left his own tiny asteroid, and visited others, until he reached the earth. It was the fox who wanted to be tamed who taught him that he must return to his own and find there the happiness and the meaning of life he had left.”

*

“…children are like sponges. They soak into their pores the essence of any book they read, whether they understand it or not … The Little Prince will shine upon children with a sidewise gleam. It will strike them in some place that is not the mind and glow there until the time comes for them to comprehend it.”

–P.L. Travers (author of Mary Poppins), The New York Herald Tribune, 1943

***

Further Reading:

How a Beloved Children’s Book Was Born of Despair