The cradle rocks above an abyss, and common sense tells us that our existence is but a brief crack of light between two eternities of darkness.

*

“Vladimir Nabokov, the bilingual writer, has at one time or another been compared to Joseph Conrad. He objects to the comparison, noting (among other things) that Conrad never wrote in Polish. He himself, of course, has become something of an acrobat, supplely curling himself between his native language, Russian, and his first literate language, English. In a now-characteristic foreword (bibliography, 18th thoughts, rabbit punches for dunderheaded critics), he elucidates the genesis of this ‘present, final edition’ of Speak, Memory, ‘a systematically correlated assemblage of personal recollections ranging geographically from St. Petersburg to St. Nazaire, and covering 37 years, from August, 1903 [when the author was 3 years old] to May, 1940 [when he migrated to America], with only a few sallies into later space-time.’ As a matter of fact, the initial essay of the series was written in French and published in Paris in 1936; the rest were in English and written in America, in an order ‘established in 1936, at the placing of the cornerstone which had already held in its hidden hollow various maps, timetables, a collection of matchboxes, a chip of ruby glass, and even, as I now realize, the view from my balcony of Geneva lake, of its ripples and glades of light, black-dotted today at teatime, with coots and tufted ducks.’ The first assemblage of these recollections was published here in 1951 as Conclusive Evidence (‘conclusive evidence of my having existed’). The English edition was retitled Speak, Memory, which sounded less like a mystery story and was on acceptable modification of Nabokov’s first choice of title, Speak, Mnemosyne, which his publishers persuaded him was commercially debilitating.

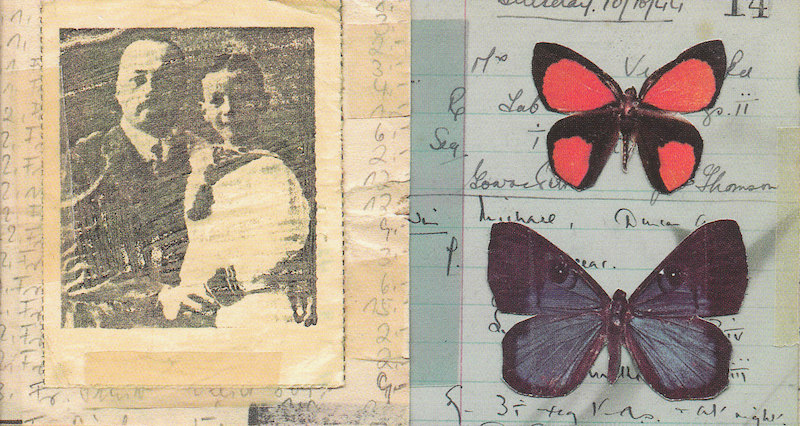

” ‘In the summer of 1953,’ he writes, ‘at a ranch near Portal, Arizona, at a rented house in Ashland, Oregon, and at various motels in the West and Midwest, I managed between butterfly-hunting and writing Lolita and Pnin, to translate Speak, Memory, with the help of my wife, into Russian. . . . For the present, final edition of Speak, Memory I have not only introduced basic changes and copious additions [most identifiably, a much amplified biography of his adored father] into the initial English text, but have availed myself of the corrections I made while turning it into Russian. This re-Englishing of a Russian re-version of what had been an English re-telling of Russian memories in the first place, proved a diabolical task, but some consolation was given me by the thought that such multiple metamorphoses, familiar to butterflies, had not been tried by any human before.’ So much for Conrad. These bibliographical data, seemingly so peripheral, are in fact central to much of Nabokov’s work, and especially to this memoir. For he is concerned first of all, and to the point of obsession, with process.

“The book is ‘about’ his extraordinary, cultured, aristocratic family and upbringing in imperial Russia, ‘the harmonious world of a perfect childhood,’ as he puts it, ad the years of exile between 1919 and 1940 in Cambridge, England, Berlin and Paris. But what primarily involves him, and makes the book a work of art, is the process of recollection, how the chip of ruby glass retrieves forgotten feelings and past events from dark corners of the prison of time in which both it and he are still and always entrapped; how what he calls the ‘spiral unwinding of things’ can be stopped and penetrated at certain points by the senses, detectives and conjurers after clues; and how this evidence reasserts itself and can be reordered, re-energized and expressed, at once transformed and re-created into memory and art. A Proustian exercise, also Joycean, also Nabokovian; and with Nabokov, the translation, reordering and extension of his own previous writing is not merely helpful to the estate but essential to his way of art, and has much to do with his early mathematical wizardry, his fascination with chess, his butterfly collecting, his (as Page Stegner notes in his recent study of Nabokov’s English novels, ‘Escape Into Aesthetics’) ‘deliberate strategy’ of blending, as if for sanity’s sake, appearance and reality in imitation of nature’s intricate deceptions and endless metamorphoses.

“It remains to be said here that Speak, Memory unmasks and evokes much that is factually fascinating. It is full of marvelous stories and fragments and portraits, especially of his liberal publisher-politician father, who was once jailed by the czar, took part in the uprising of March, 1917, and in the Lvov provisional government, fled the Bolsheviks (the author left behind a $2-million inheritance) and was assassinated by monarchists in Berlin in 1922. The Nabokov residences, a town house in St. Petersburg, a country villa with ‘a permanent staff of about 50 servants and no questions asked’ nearby, and the various wealthy watering-holes of Europe are all wonderfully described. At the end, there is still the process, a source of art as well as of the meld of attitude it constantly, continuingly and cunningly takes on, a cross of farce and anguish. One is reminded throughout of a television interview done with Nabokov a year or so ago at his present home in Montreux, Switzerland. At the fadeout, the screen showed the view from Nabokov’s terrace, while the author’s voice could be heard in the background testing various pronunciations of his name, as if to see what each might now trick away from time, unmask, unlock, evoke. ‘Nabokov,’ you could hear, ‘NAbokov, NabOkov, Nabookov. . . .’ ”

– Eliot Fremont-Smith, The New York Times, January 9, 1967