I first found Jeanette Winterson in college, at a time when I thought writing about love was starting to feel trite and juvenile. But Jeanette Winterson does it differently. She calls on the Old Book and oral tradition, tangles in myths and historical events, and tells them again in the service of her story.

She is the perfect author to get obsessive about/with because she, too, obsesses: over love, over motherhood, over the construct of time, over having a body, over language. In each of her novels, you can watch her attack the same subjects in a different story, with a new cast in a new world. Jeanette Winterson has taken her readers from the shores of Mary Shelley’s Lake Geneva to the Venetian canals of the early nineteenth century to the labyrinth of cyberspace.

I have this theory that Jeanette Winterson books come into your life exactly when you need them. It’s why I only read her backlist titles when I’m browsing through some used bookstore and they find me. But now, here, I’m handing these titles to you. Do with them what you will.

*

Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit (1985)

I can put these accounts together and I will not have a seamless wonder but a sandwich laced with mustard of my own.

You must start here. Considered required reading in a lot of contemporary fiction classes and a classic of LGBTQ literature, Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit is her first novel. This powerful debut, which won the Whitbread Prize for Best First Fiction back in 1985, loosely follows the actual events of her life but is very much a work of fiction. (The memoir comes later.) Meet Jeanette: adopted into a very conservative and religious English Pentecostal family. When she’s a teenager, she falls in love with a woman and runs away. The brilliant and clever and very Jeanette Winterson thing about it, though, is that she structures the book like the Bible. The first bit is called Genesis. Deuteronomy is a key chapter that, in a way, teaches you how to read the book (how to eat this sandwich laced with mustard of her own!). In framing her story like this, she becomes her own God.

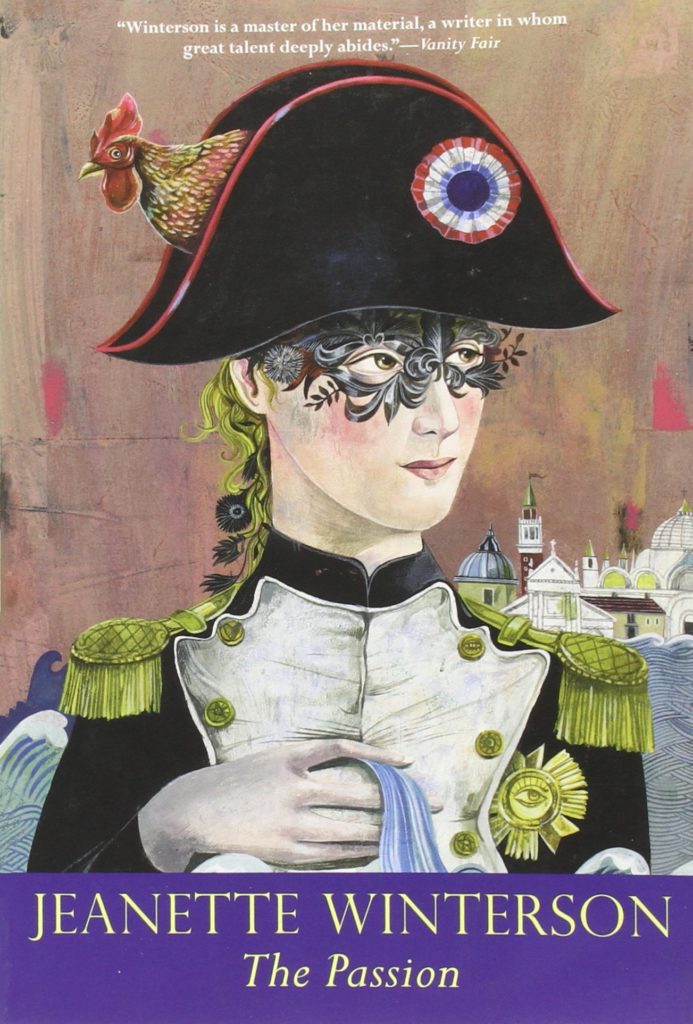

The Passion (1987)

I’m telling you stories. Trust me.

Published just two years after her wildly successful debut, The Passion continues to pick at familiar themes: religion, or the people we worship, and the things we risk for love. (At a casino, a heart is gambled away.) It’s set against the backdrop of the Napoleonic Wars. Napoleon himself is a character. The opening line reads: “It was Napoleon who had such a passion for chicken that he kept his chefs working around the clock.” To take a historical figure and start at an absurd, intimate detail like this! She does it with such confidence. The thing about Jeanette Winterson is that she doesn’t so much ask where she would fit into the myth or the history as she does spin the known-stories around her own narrative. In The Passion, we follow Henri (one of Napoleon’s most faithful soldiers) and Villanelle (the daughter of a gondolier). The whole thing sort of reads like a fever dream, and what better place for their stories to intertwine than the unreal, sinking city of Venice? At the mercy of Jeanette Winterson’s winding, lustful language, it all feels so doomed and fated. Even though the facts of the story feel far away, the way she tells it makes it feel urgent. (Much like love.) She breaks the fourth wall a lot in this novel, breathes right in your face when she repeats lines like, “I’m telling you stories. Trust me,” and “You don’t believe me? Go and see for yourself.” She dares you to step in.

Written on the Body (1992)

Written on the body is a secret code only visible in certain lights: the accumulations of a lifetime gather there.

Some people consider this a departure from Jeanette Winterson’s earlier work (this is her fourth novel), and sure, it’s not quite as fantastical, but it remains my personal favorite. She really doesn’t shy away from sentimentality. It’s not everyone’s cup of tea, but I can’t stop thinking about these lines from the very first page: “‘I love you’ is always a quotation. You did not say it first and neither did I, yet when you say it and when I say it we speak like savages who have found three words and worship them.” Written on the Body focuses on an affair between the narrator (given neither name nor gender) and a married woman. The cloaked identity of the narrator that makes it a guessing game, at first, and then the importance of knowing these things falls away in the face of their love. It’s different than when the key players are Jeanette or Napoleon. There’s something about the ambiguity of the situation that feels as though you could be in it. At its core, I think Written on the Body does what Jeanette Winterson does best. It invites you in, it guts you, but it’s playful. It also plainly states her interest in looking at the body as a physical manifestation of your personal story, which is a nice segue into the next…

Frankissstein (2019)

My mind idled around the difference between desire for life without end and desire for more than one life, that is, more than one life, but lived simultaneously.

This may be Jeanette Winterson’s newest novel (released in the US just yesterday), but it moves through a huge chasm of time. She brings us back to 1816, where we begin with Mary Shelley and her artsy cohort on holiday at Lake Geneva. Only this writer would think to take us from there to Brexit Britain, to a world of artificial intelligence and sex robots (and the possibilities of combining the two). The amazing thing about reading Jeanette Winterson through the decades is her stories absorb whatever technological advances surface. (Case in point: The PowerBook, which she published in 2000, focuses on a woman named Ali who will email anyone a story upon request. She promises “freedom just for one night” but with the caveat that what they find might change them. The PowerBook blurs imagination and reality while cutting right to the heart in a way we’ve seen her do before… but with email!) But to her, the concept of a post-human future made possible through technology isn’t necessarily introducing something new. To Jeanette Winterson, it’s always all connected. Having a body, wanting another—that’s the same thing as writing yourself into a new story. She does this all the time. (Deep Dive: Jeanette Winterson talking about the future of humanity in a tech-dominated world over on Lit Hub.)

Why Be Happy When You Could Be Normal? (2013)

If the sun is shining, stand in it—yes, yes, yes.

Once you’re finally, absolutely, over-the-moon obsessed with Jeanette Winterson, it is time to pick up her memoir. But only when you’ve read and fallen in love with the rest of her oeuvre! Why Be Happy When You Could Be Normal? is extremely self-referential and, I feel, written for the super fans who have been on this journey with her. If this applies to you, you know the outer lines already. Throughout, she throws in echoes of the central, haunting questions from each of her books. (Why is the measure of love loss?) As promised, you’ll recognize bits from her first foray, Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit. But the telling takes a different shape this time around. The story hits harder because it comes from a writer who has spent so long grappling with grandiose myths but whose own family mythology has loomed over her all the while. Here, she addresses it head-on, inviting us to join her in her search for her biological mother. And, yes, in memoir she’s still a luscious and lyrical storyteller, but there are notable moments when the writer-Jeanette facade cracks and we see through to a person and a story she’s been throwing herself at all along.