“I don’t know myself, what to do, where to go … I lie in the crack of a book for my comfort.”

*

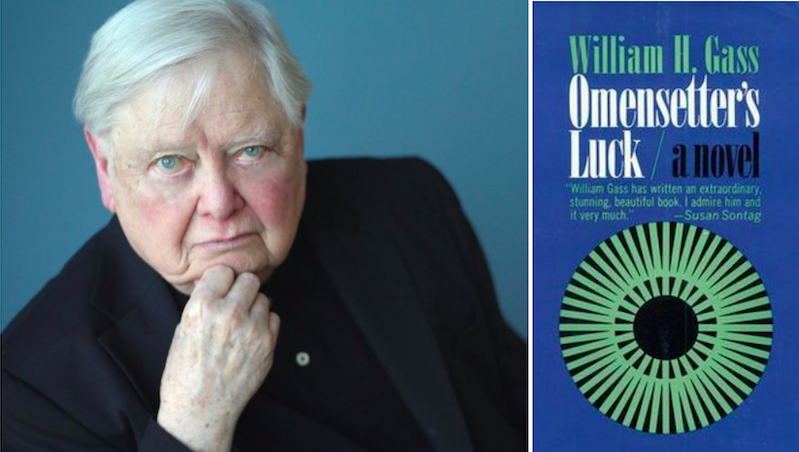

“For his first novel William H. Gass couldn’t have chosen a less fashionable setting. And he couldn’t have been more oddly successful because—not in spite—of it. Omensetter’s Luck takes place in Gilean, a backwater town on the Ohio in the backwater period of the 1890’s. Gilean is ‘Amurrica’ at its squarest, drowsing in church suppers, gossipping on chaw-tobaccy-stained porches, clippety-clopping along a Main Street whose dullness would have appalled Dr. Kennicott. And out of just this stale territory the author has managed to carve relevant and urgent metaphors of mortality and salvation.

Only talent has such nerve. The world with which Mr. Gass works here has long been exhausted, you would think, not only by Sinclair Lewis but by the likes of Sherwood Anderson and Edgar Lee Masters. Certainly all the hip little novelists nowadays have abandoned it for the chic regions of drug addiction and alcoholic trauma, jet-set sodomy and the dropout’s novel of ideas. Mr. Gass, though he leads us into many a terrifying vision, does not resort to a single routine apocalypse. And yet, while the costumes of the book may be historical, its impact is compellingly modern.

“The surface movements of the story can be summed up in two paragraphs. Brackett Omensetter drives into Gilean one day with his wife and two daughters. It quickly becomes apparent that as other people have green thumbs, he has a green soul. The cosmos and he live in mysterious congruity. When Omensetter neglects to cover his wagon, the clouds melt away; when he applies a quack poultice to a lockjaw wound, the patient lives; and when Omensetter meets a stranger, neither shyness nor vanity constrains his tongue. A preternatural rightness flows from his presence. His luck is that he has not yet come upon the tree of knowledge.

Such impervious blitheness inflames the Rev. Jethro Furber, his great counter-pole in Gilean; it disturbs many others, most of all Henry Pimber, Omensetter’s landlord. A sort of envy of his tenant drives Pimber weirdly but inexorably into the woods, into a queer death resonant with symbols. The event shakes the town. It takes Eden away from Omensetter. As his luck departs him, he leaves Gilean, and the town once more resumes its gossip and its torpor and the daily dusty entanglements of ulterior motives.

“A small plot, then, but constantly fecund with tiny twists and sudden juxtapositions that flash into significance. Gass’s stagecraft is cunning. The book opens in the 20th century to the noises of an auction selling off items in the Pimber house. An old man, listening,muses back to Henry Pimber’s death and thus to Omensetter’s arrival. Pimber comes alive, in a brief section, as a narrow but straining soul, a soul at once kindled and victimized by the charisma of the newcomer. And then, for the three quarters of the novel that remain, the glittering jeremiad of Furber begins, directed against himself.”

–Frederic Morton, The New York Times, April 17, 1966