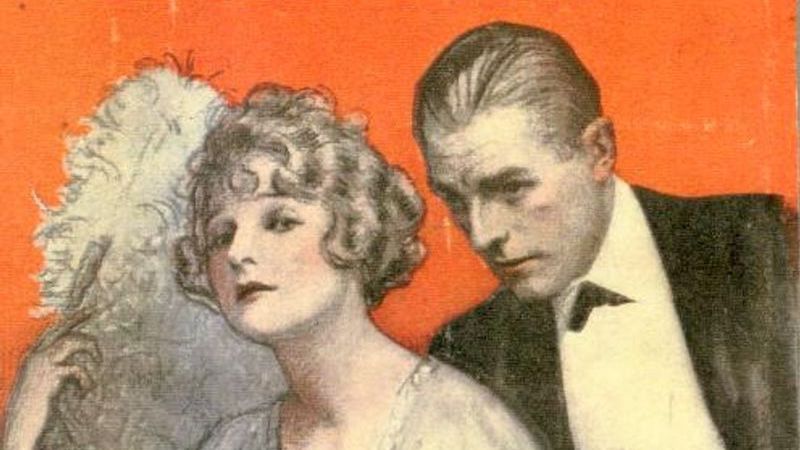

This Side of Paradise—the then-23-year-old F. Scott Fitzgerald’s star-making autobiographical debut, a tale of narcissism, greed, and warped love, which famously helped F. Scott secure Zelda’s hand in marriage—is a century old this year. Where does the time go, eh?

To mark this literary centennial, here’s one of the earliest reviews of the novel, published in the New York Times just a month after the two were wed.

I don’t want to repeat my innocence. I want the pleasure of losing it again

*

“The glorious spirit of abounding youth glows throughout this fascinating tale. Amory, the romantic egotist, is essentially American, and as we follow him through his career at Princeton, with its riotous gayety, its superficial vices, and its punctilious sense of honor which will tolerate nothing less than the standard set up by itself, we know that he is doing just what hundreds of thousands of young men are doing in colleges all over the country. As a picture of the daily existence of what we call loosely ‘college men,’ this book is as nearly perfect as such a work could be.

“The philosophy of Amory, which finds expression in ponderous observations, lightened occasionally by verse that one thinks could have been evolved only in the cloistered atmosphere of his age-old alma mater, is that of any other youth in his teens in whom intellectual ambition is ever seeking an outlet. Amory’s love affairs, too, are racy of the soil, while the girls, whose ideas of the modern development of their sex seem to embrace a rather frequent use of the word ‘Damn,’ and of being kissed by young men whom they have no thought of marrying, quite obviously belong to Amory’s world. Through it all there is the spirit of innocence in so far as actual wrongdoing is implied, and one cannot but feel that the sexes are well matched according to the author’s presentment.

“Amory Blaine has a well-to-do father and a mother who lives the somewhat idle, luxurious life of a matron who has never known the pinch of even economy, much less of poverty, and the boy is the creature of his environment. One knows always that he will be safe at the end. So he is, for he does his bit in the war, finds afterwards that his money has all gone and goes to work writing advertisements for an agency. Also, he has his supreme love affair, with Rosalind Connage, which is broken off because the nervous temperaments of both would not permit happiness. At least, so the girl thinks. So Amory goes on the biggest spree noted in the book-a spree which is colorfully described as taking in everything in the alcoholic line from the Knickerbocker ‘Old King Cole’ bar to an out-of-the-way drinking den where Amory is ‘beaten up’ artistically and thoroughly. The whole story is disconnected, more or less, but loses none of its charm on that account. It could have been written only by an artist who knows how to balance his values, plus a delightful literary style.”

–The New York Times, May 9, 1920

If you buy books linked on our site, Lit Hub may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.