Our smorgasbord of sumptuous reviews this week includes Rebecca Makkai on Dinaw Mengestu’s Someone Like Us, David Klion on John Ganz’s When the Clock Broke, Ursula Lindsey on Isabella Hammad’s Enter Ghost, John Wray on Bret Anthony Johnston’s We Burn Daylight, and Heller McAlpin on Jessica Anthony’s The Most.

“Secrets are the enduring motors that make fiction run: what you aren’t telling me, what I’m keeping from you, what the neighbors know about the love affair. Dinaw Mengestu’s novels are powered by something different but akin: an urge toward privacy that keeps his mercurial characters elusive, even to themselves, but not opaque … As a driver of plot, personal and emotional slipperiness is a trickier endeavor than old-fashioned secrecy; we can’t rely on the well-timed reveal, the moment when all is made clear, nor enjoy knowing more than the characters while waiting for them to catch up. To appreciate Mengestu’s work, you have to be ready to live in uncertainty, to find any truths obliquely, if at all. If you can accomplish that, the journey is well worth the discomfort … That’s the narrative trick of this entire novel, in fact; you’re going to catch the real only out of the corner of your eye. Don’t bother trying to look at things directly because all you’ll see are the cover stories and lies … This might not be the novel that earns him broad popular acclaim…but it’s the book that ought to cement Mengestu’s reputation as a major literary force.”

–Rebecca Makkai on Dinaw Mengestu’s Someone Like Us (The New York Times Book Review)

“These uncertainties about a liberal future sit at the center of John Ganz’s accomplished debut, When the Clock Broke: Con Men, Conspiracists, and How America Cracked Up in the Early 1990s. While many Americans in 1989 ‘believed they were witnessing the ultimate victory of liberal democracy,’ Ganz notes, ‘others thought they were observing its death throes.’ A whirlwind tour of the myriad right-wing insurgencies that punctuated the George H.W. Bush years, When the Clock Broke presents the post–Cold War United States not as a victorious empire but an ailing nation plagued by deindustrialization, racist militias, millenarian sects, extremist demagoguery, urban unrest, conspiracy theories, and generalized despair. If that sounds a lot like the Trump era, well, that’s precisely Ganz’s point. Trump’s election in 2016, he writes in his introduction, ‘represented the crystallization of elements that were still inchoate in the period of this book.’ The supposedly ascendant United States at the end of history, in other words, already demonstrated all the symptoms of its present maladies … Ganz tends to use an immersive approach to writing about the past: When the Clock Broke not only recounts but seeks to approximate the experience of living through 1989 to 1993 … Ganz’s subjects, to paraphrase Kamala Harris, didn’t just fall out of a coconut tree—they exist in the context of all that came before them (an essentially Marxist insight). If, like Ganz, you are an older millennial, you might experience When the Clock Broke as I did—as an informed adult’s reconsideration of what our parents were muttering about at the dinner table back when we were learning how to add and subtract. It’s to Ganz’s great credit that he is able to write about both wider historical trends and idiosyncratic biographical details while also keeping his story lively and amusing.”

–David Klion on John Ganz’s When the Clock Broke: Con Men, Conspiracists, and How America Cracked Up in the Early 1990s (The Nation)

“Hammad’s novel depicts a strikingly rich and complicated spectrum of Palestinian identity and experience. It draws out the differences and frictions among Palestinians who live in a difficult city like Hebron, in daily confrontation with Israeli settlers, and those who reside in the more protected ‘Ramallah bubble’ under Palestinian administrative control; among those who have the relative privilege of Israeli citizenship, those who grew up in refugee camps, and those who live abroad and feel guilty or defensive about it. Hammad draws out the divides and silences between generations—when Sonia questions her father about his youthful militancy, he tells her, ‘Forget about it, my love. Palestine is gone. We lost her a long time ago.’ She also pays attention to the way the occupation affects men and women differently … the idea of Palestinians as ghosts—haunting history, the land, Israelis themselves—runs through Hammad’s novel…But Hammad’s story complicates and enriches the ghost metaphor in unexpected ways…Being a ghost is a way not of being erased but of escaping and enduring, of staying in the story, of returning (to that supposedly empty stage) as the plot’s very catalyst. The ghost, after all, enters.”

–Ursula Lindsey on Isabella Hammad’s Enter Ghost (The New York Review of Books)

“What is it about cults? We can’t seem to get enough of them…We love these stories, I’d argue, for the same reasons people are drawn to cults themselves: the promise of a radical alternative, of emancipation from ourselves, of ideological cover for bad behavior, of simple (if theologically arcane) answers to life’s complex, intractable problems. Religious extremists beguile us just slightly more than they frighten us, which is enough to keep them in business … Johnston invests his characters—both the justifiably suspicious Waco townsfolk and the slightly cuckoo members of the sect, whose doomsday prophet has taken to calling himself ‘the Lamb’—with intelligence, idiosyncrasy and wit … The Lamb himself (who, various disclaimers are at pains to make clear, is not David Koresh, of the infamous Branch Davidians) is one of the novel’s most gratifying creations: a charming bumbler, a self-aware true believer, a gullible, fallible angel of death. You fear what the Lamb will set in motion, no question, but somehow you don’t fear the Lamb. By the novel’s inevitable fire-and-brimstone conclusion, you may find that you’ve grown fond of him in some perverse, complicit way, and even miss him a little when it’s over … Ultimately, what keeps us reading a novel is the promise of revelation, and it’s in the smallest and most seemingly off-handed of its surprises that We Burn Daylight is most alluring. The ending may be tied up in slightly too tidy a bow for my taste, but it seems somehow petty—prideful, as the Lamb might say—to complain. By then, after all, we’ve already been taken on a darkly dazzling pilgrimage of violent delights, and violent ends.”

–John Wray on Bret Anthony Johnston’s We Burn Daylight (The New York Times Book Review)

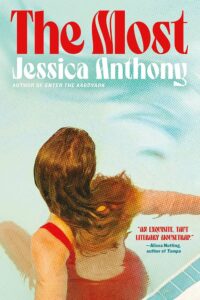

“Jessica Anthony’s new novel, The Most, blindsided me with its power, much like the cunning tennis strategy from which it gets its title. I don’t say this often, but this superb short novel, about a marriage at its breakpoint, deserves to become a classic … With its echoes of John Cheever’s ‘The Swimmer’ and its midcentury details, we’re expecting a new take on 20th century suburban malaise. But what we get—along with the green wall-to-wall carpet, the ominous launch of Russia’s Sputnik 2 carrying a doomed ‘Muttnik’ named Laika into space, the ’57 Buick Bluebird provided by Virgil’s new employer, Equitable Life, against future sales that have not yet materialized—is a story about tradeoffs in marriage and life … Kathleen, adrift in the pool, intends to blow things up, to detonate the status quo. Her deployment of this stratagem is at once a trap—to force Virgil’s hand—and a passage, so they can move on together. With The Most, Anthony has served an ace.”

–Heller McAlpin on Jessica Anthony’s The Most (NPR)