A Supreme Court gladiator, a firebrand punk feminist, and an Old Hollywood megalomanic all feature among the creme of the review crop this week.

In her Atlantic piece on Jane Sherron De Hart’s Ruth Bader Ginsburg: A Life, Dahlia Lithwick considers the enduring appeal of everyone’s favorite octogenarian lawmaker, writing that Supreme Court Justice Ginsburg “is less a radical feminist ninja than a meticulous law tactician—and she has become what we dream of for our toddler daughters.”

Over at The New Republic, Joanna Scutts calls Seduction—Hollywood historian Karina Longworth’s account of the women who lived under Howard Hughes’ tyrannical influence— “an insistent, clear-eyed reminder of the fact that history does not get buried or forgotten by accident, but by design, in order to burnish and elevate the reputations of powerful men, and to cut women down to size.”

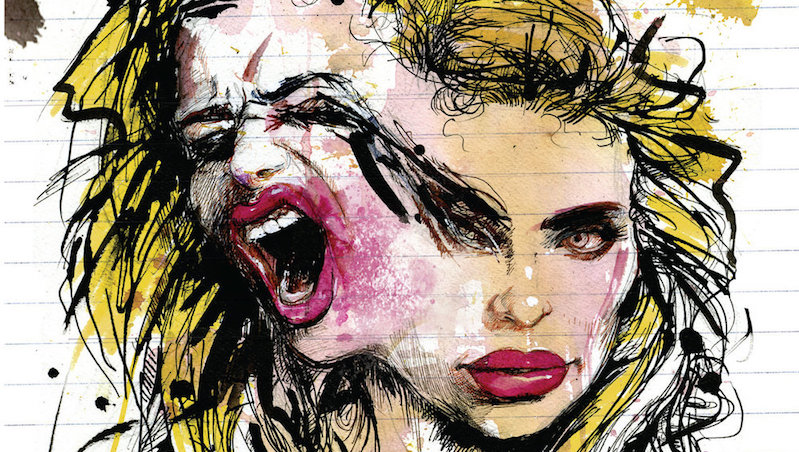

Lauren Oyler, in her Bookforum essay on the radical voice of cult French author Virginie Despentes, describes Despentes’ brand of feminism as the rare kind “that insists on the value of individual agency even as it acknowledges and criticizes a net of systemic pressures that seem to render that agency very difficult to exercise.”

We’ve also take a closer look at Lisa Brennan-Jobs’s New York Times review of The Day That Went Missing—Richard Beard’s attempt to rebuild the life of the brother he lost to drowning—and Katy Waldman’s New Yorker take on James Geary’s Wit’s End—an ebullient exploration of every facet of wit.

*

“The women of the Trump resistance are livid. Books about women and fury fill the tables in every bookstore. And yet, above all, Ginsburg models the fine arts of civility and diligent case citation. She is less a radical feminist ninja than a meticulous law tactician—and she has become what we dream of for our toddler daughters … In a revealing new biography, 15 years in the making, Jane Sherron De Hart helps untangle the mystery of the decorous Ginsburg as feminist gladiator…She traces Ginsburg’s path from precocious Brooklyn schoolgirl to the most formidable women’s legal advocate in modern history, and no bras are burned, no political arrests are made, no Saint Crispin’s Day speeches are delivered along the way. Instead, De Hart scrupulously renders a rule-abiding, institutionalist, cautious lawyer and then judge who has managed to remake constitutional history precisely because of those qualities, not despite them … Ginsburg’s enduring feminist secret seems to be that, even in a time of reality-show presidential rule and shifting narratives, she remains unwaveringly who she has always been—as controlled, at the core, today as she was in the now-vanished world of postwar Brooklyn. I’m not sure that Ruth Bader Ginsburg has ‘caught up’ to modern feminism, or that it has caught up to her.”

–Dahlia Lithwick on Ruth Bader Ginsburg: A Life (The Atlantic)

*

“Seduction offers an insistent, clear-eyed reminder of the fact that history does not get buried or forgotten by accident, but by design, in order to burnish and elevate the reputations of powerful men, and to cut women down to size … Instead of focusing on Hughes as the hero (or anti-hero), as most Hollywood histories have tended to, she instead seeks out the stories of the women who lived and worked in the riptide of his influence. By unearthing unpublished material from the archives of Hughes and his contemporaries, and, more often, by astutely reading between the lines of official histories, Longworth shows how valuable and revealing it is to tell the story of a playboy from the perspective of his toys … It is tempting to shuffle possible, posthumous diagnoses of Hughes, whether they’re cultural or medical: head trauma from one too many plane crashes; undiagnosed epilepsy (perhaps the cause of all those crashes); secret syphilis; that hypochondriac mother. But as Longworth makes clear, a focus on ‘what went wrong’ in his later years requires that we see the younger Hughes as basically decent and healthy—and it’s only possible to do that if we think it’s really no big deal to scout young women as though the entire world is a catalog, and then, essentially, to purchase and imprison them. In other words, if we celebrate megalomania and gilded male privilege run amok as quintessential American values.”

–Joanna Scutts on Karina Longworth’s Seduction: Sex, Lies, and Stardom in Howard Hughes’ Hollywood (The New Republic)

*

“The thing about childhood is that you don’t understand how strange it is until you look back as an adult. While you’re inside it, it’s all you know. But Beard notices that Nicky is eerily absent from the family story; he doesn’t even know the date of his brother’s death. Nicky is not kept on a pedestal, as we might imagine, but remembered as less remarkable, less talented and less promising than he was, even by his mother … The reader is carried along on the twists and turns of the inquest, from the basics (the date, the beach, the rental house) to Beard’s ineffectual research (he loses his map, interrupts during interviews) to the profound (the discovery of a lost story), so that the book is not only a memoir but a chronicle of how lost memories can be recovered. It is a memoir that reveals the mechanism of the form itself … This is a story of a man trying to feel and succeeding, we hope, in the end. If the beginning is dense with theory and fact gathering, the later part of the book swells with meaning and revelation. Beard cops to his own guilt and sadness and the memories themselves, after much research and focus, become lush and full. But when he finally visits the exact beach at the exact time of the event that happened so many years before, he does not jump in. He only wades up to his knees.”

–Lisa Brennan-Jobs on Richard Beard’s The Day That Went Missing (The New York Times Book Review)

*

“Rarely a purely theoretical writer, Despentes draws on her experience in low-wage jobs and stints as a prostitute, stripper, and porn reviewer to fully depict the entanglements of class and gender. Her subjects range from the near inescapability of traditional standards of beauty to the marriage contract as a form of prostitution much more degrading to women than sex work itself (which is, in Despentes’s view, a way to claim agency) to the puritanical pressures women face from both sexes … This was no utopia, yet there’s something appealing about it: a glimmer of possibility that freedom for women wouldn’t require the forfeiture of individual will to either institutions or ideology. What happened? Despentes’s work is both an answer to that question and an attempt to find an alternative … This duality—the radical voice in the hot body, the matter-of-fact wisdom espoused by the punk—informs all of Despentes’s work. While her characters are often queer and gender-bending, Despentes understands that stereotypical differences between men and women, born of patriarchal pressure but often exacerbated by bad personalities, aren’t necessarily inaccurate, either … Despentes’s is a rare feminism that insists on the value of individual agency even as it acknowledges and criticizes a net of systemic pressures that seem to render that agency very difficult to exercise.”

–Lauren Oyler on the punk feminism of Virginie Despentes (Bookforum)

*

“That there is a trickster beauty to reality’s mechanics is the unlikely takeaway of Wit’s End…Wit—that eerie quick flair, an almost clairvoyant fitted-to-circumstance-ness—sees ambiguity and mines it; it becomes a strategy for negotiating doubleness with grace. Wit, equal parts Darwinian and deconstructionist, promises elasticity and attunement in the garbage world of 2018, where meanings don’t stay still … [Geary] designates the lowly pun as the kernel from which all other forms of wit grow—puns, he proposes, are ‘compressed detective stories,’ yoking strange associates together. One ‘solves’ them as one might lay bare a conspiracy—what do gorges and gorgeous have in common? (Per a municipal motto, Ithaca is both.) Wit’s End sometimes treats these devices the way Freud treated dream images: as supercharged particles, burls that mark the convergence of multiple trains of thought … For the most part, the formal shifts playfully enact the notion of wit as ‘improvisational intelligence that allows us to think, say, or do the right thing at the right time in the right place.’ Yet something about this subject matter remains elusive. What makes a comment witty?”

–Katy Waldman on James Geary’s Wit’s End: What Wit Is, How It Works, and Why We Need It (The New Yorker)