Our carnival of commendable criticism this week includes Yiyun Li on Elizabeth McCracken’s The Hero of This Book, Catherine Lacey on Gwendoline Riley’s My Phantoms and First Love, Megan O’Grady on Yiyun Li’s The Book of Goose, Laura Miller on Elizabeth Strout’s Lucy by the Sea, and Ryan Ruby on Ian McEwan’s Lessons.

“I wonder if this is the first time that St. Paul’s has been compared to an elk. Some writers describe human habitats eloquently; others write about nature with wisdom. McCracken sees the elk in the middle of London, an image that perfectly encapsulates the essence of her fiction: seemingly nonsensical and yet making perfect sense. The world, strange in the first place, is often made stranger by our minds. McCracken captures the twilight zone between consciousness and subconsciousness, where intuitions are not yet filed away, impulses not yet stifled … I could easily see McCracken’s new book saddled with one of those systems: this is a novel about loss and grief; a novel about resilience and renewal; a novel about a mother-daughter relationship; a novel aboutwriting. These descriptions depict the book the way I was taught to draw a bird in kindergarten: a circle for the head, an oval for the body, two triangles for the wings. But McCracken is one of those fleet-footed writers who will never be trapped, or even reliably tracked, by aboutness … Like Elizabeth Bowen and Penelope Fitzgerald before her, McCracken is good at capturing those shadowy impressions and fleeting thoughts at the corner of the mind’s eye, leaving the reader with a sensation of reliving something, though whether it’s the past or the future one cannot be certain. Has her work brought us back to long-buried memories, or to anticipations and imaginations that we have yet to articulate? … The secret of McCracken’s writing, one may venture to say, is her relationship with her characters. She knows and loves them: body and soul.”

–Yiyun Li on Elizabeth McCracken’s The Hero of This Book (Harper’s)

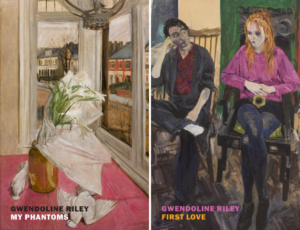

“In the world of Gwendoline Riley’s novels, a parent’s love is not to be trusted. What should come innately here seems skewed and conditional. A reader gets the clear sense that nothing—not even this supposedly pure emotion—comes without a cost … There are so many similarities between these two novels that a chapter from one could be inserted into the other with little disruption. In this way, My Phantoms and First Love function almost as a diptych, shining light upon and reflecting each other’s concerns and questions. In both, we see a youngish woman trying to love and be loved. In both, a self-centered mother is rendered in exacting, withering detail. In both, an estranged father is dead … Anyone who has been in an emotionally toxic relationship will startle with recognition, and anyone curious about what it’s like could well start here … Both books burst with these sorts of aching dialogues, punctuated with endings that come out of nowhere—a knife stabbing a proclamation to a wall … These episodes of domestic dislocation reminded me, at certain moments, of Raymond Carver’s lost, love-hungry men and women. Like Carver’s, Riley’s characters lunge at one another again and again, trying to get a moment of pure human connection and coming away instead with bruises.”

–Catherine Lacey on Gwendoline Riley’s My Phantoms and First Love (The Atlantic)

“Li, of course, has never been the kind of writer who tells you what you want to hear, and this is surely part of why she has become, while still in her 40s, one of our finest living authors: Her elegant metaphysics never elide the blood and maggots. Agnès and Fabienne succeed in creating a thrillingly illicit world of their own making, one that acknowledges their pain, but Li doesn’t flinch from the girls’ emotional fascism. The indifferent cruelty of the village is re-enacted both in the fictional realm they’ve built and in the way they manipulate, with grave consequences, their real-world elders. Aspects of their hothouse friendship may initially invite comparison to Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan novels, but as the novel progresses and Agnès lands, at the behest of a P.R.-savvy headmistress, in a British finishing school, I was reminded of the cooler registers of Fleur Jaeggy and Muriel Spark. Their relationship becomes an epistolary one—Fabienne sends Agnès letters under both her own name and that of an invented suitor—and the rules of the game, of their friendship, and indeed, of the novel itself, become increasingly ambiguous … All fiction is a kind of hoax in that it spins a delusion, inciting genuine feelings with invented characters and situations. The most propulsively entertaining of Li’s novels, The Book of Goose is an existential fable that illuminates the tangle of motives behind our writing of stories: to apprehend and avenge the truth of our own being, to make people know what it feels like to be us, to memorialize the people we keep alive in the provincial villages of our hearts. But it’s the motives behind our impulse to read fiction, and why we enter this delusion so eagerly, that occupied me through Li’s novel: the desire to suspend life in order to return to it more specifically and more vividly known to ourselves—and perhaps in order to believe, despite all evidence to the contrary, in our own consequence.”

–Megan O’Grady on Yiyun Li’s The Book of Goose (The New York Times Book Review)

“Like all of Strout’s novels, Lucy by the Sea has an anecdotal surface that belies a firm underlying structure. It is meant to feel like life—random, surprising, occasionally lit with flashes of larger meaning—but it is art. The Shaker plainness of Strout’s prose stretches to accommodate Lucy’s bewilderment as she goes about her life’s great project: attempting to understand the people around her … Strout builds her fiction out of moments like these, little slights and kindnesses that make up the architecture of human relationships. Readers of the series will recognize that Lucy’s labile emotions must be a bit exhausting…She is an utterly believable mixture of solipsism and sympathy, just as William is both an indifferent confidant and a stalwart protector … The intimacy of Strout’s fiction doesn’t lend itself particularly well to topicality, and as the novel careers through recent catastrophes, from the covid death count in New York to the murder of George Floyd and the January 6th insurrection, its voice occasionally becomes stilted. The appeal of Lucy Barton lies in the immediacy with which she experiences the people and the events around her, but here, like so many Americans during the pandemic, she engages with the world primarily through screens, reading the obituary of a friend on a Web site and watching the Black Lives Matter protests on TV. Lucy’s responses to all this feel generic and a bit on the nose … There is a naïve purity to Lucy that has made her precious to countless readers of Strout’s work, and a little of that is lost when she second-guesses her short story and sets it aside. In a novel full of losses—for Lucy and William are of an age when losses come frequently—this is a small one, but it stings all the same.”

–Laura Miller on Elizabeth Strout’s Lucy by the Sea (The New Yorker)

“Fame has been kind to Ian McEwan, but not to his writing…As befits a regular of the international festival circuit with the occasional byline in the Guardian opinion page, his treatment of issues such as the Iraq War, climate change, euthanasia, artificial intelligence and Brexit could be described as narrativized punditry. For this, McEwan has been rewarded with increasing extra-literary prominence … Everything in Lessons, whose story concludes within a year and a half of its publication date, gives the impression of having been written in extreme haste … Within the first fifty or so pages, Roland experiences no fewer than three portentous epiphanies, none of which turn out to have any bearing on the subsequent four hundred, as though they were narrative coupons McEwan cut out but forgot to cash in. McEwan’s novel is not so much an epic as it is three novellas in a trench coat … If this all sounds pat, it has less to do with the necessary evil that is plot summary in book reviewing, than to the didacticism with which McEwan imparts these and other praecepta in the novel itself … The historical events appear to serve two narrative functions: as substitutes for the kinds of concrete details other novelists use to convey the quiddity of a character’s experience of the world and as markers for the passage of time … Just as people living behind the Iron Curtain had no shortage of reading material as mediocre as Lessons, the market is currently condemning far better books than it to smaller print runs than a samizdat. A bestselling, Booker Prize-winning Commander of the British Empire, McEwan is not obscure, nor is he powerless…Lessons was written in perfect freedom. What did he need it for?”

–Ryan Ruby on Ian McEwan’s Lessons (New Left Review)

If you buy books linked on our site, Lit Hub may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.