Our basket of brilliant reviews this week includes Ron Charles on Lauren Groff’s Matrix, Dwight Garner on Colm Tóibín’s The Magician, Laura Miller on Stephen Graham Jones’ My Heart is a Chainsaw, Lara Feigel on Frances Wilson’s Burning Man, and Joanna Scutts on Amy Argetsinger’s There She Was.

“Now that we’ve endured almost two years of quarantine and social distancing, [Groff’s] new novel about a 12th-century nunnery feels downright timely … We need a trusted guide, someone who can dramatize this remote period while making it somehow relevant to our own lives. Groff is that guide largely because she knows what to leave out. Indeed, it’s breathtaking how little ink she spills on filling in historical context…though it covers more than 50 tumultuous years, this entire novel wraps up in the space it would take Ken Follett to warm a cauldron of gruel … Though Matrix is radically different from Groff’s masterpiece, Fates and Furies, it is, once again, the story of a woman redefining both the possibilities of her life and the bounds of her realm … Although there are no clunky contemporary allusions in Matrix, it seems clear that Groff is using this ancient story as a way of reflecting on how women might survive and thrive in a culture increasingly violent and irrational. The costs and sacrifices are high, but on a planet grown ‘too hot to bear humanity,’ who isn’t tempted to have faith in the possibilities of a small society of like-minded believers walled off from the flames?”

–Ron Charles on Lauren Groff’s Matrix (The Washington Post)

“Most who attempt it focus on a small sliver of a writer’s life, the way Jay Parini did with Tolstoy’s final year in The Last Station (1990), or Michael Cunningham did in his pointillistic The Hours (1998), about Virginia Woolf and two other women over the course of a single day. In The Magician, Toibin seeks to grasp the entirety of Mann’s life and times, the way a biographer might, and he does so quite neatly. Maximalist in scope but intimate in feeling, The Magician never feels dutiful. Like its subject, it’s somber, yet it’s also prickly and strange, sometimes all at once … Toibin is a writer of pinging dialogue, a novelistic Tom Stoppard, and he gives Katia many of the best lines … Toibin, who is himself gay, has always extended historical sympathy to sexual outsiders. As he’s written elsewhere, ‘There are no 19th-century ballads about being gay.’ The pained sublimation of homosexuality in Mann’s work, especially in The Magic Mountain, set in a tuberculosis sanitarium, could make it resemble an illness. Toibin’s fiction is animated by the ever-alert attention he pays to sexual subcurrents … The great theme of Toibin’s novel, as in much of Mann’s fiction, is decline—of manners and morals, of families, of countries and institutions. Thomas and Katia were increasingly remnants from an older world, a fact of which they were poignantly aware.”

–Dwight Garner on Colm Tóibín’s The Magician (The New York Times)

“My own horror fandom doesn’t typically extend to slashers, which have always seemed overly predictable and rigid to me, fueled by an inchoate teenage rage too far back in my own past to feel immediate. But Jones makes the case for the slasher as the sestina of adolescent fury; the very inflexibility of the form at once both weirdly comforting and a daunting challenge to anyone seeking to do anything original with it … Literary novels—which is what My Heart Is a Chainsaw, for all its reveling in trashy pop culture, really is—care as much about character as plot, so the mystery here is equal parts ‘Who is the slasher?’ and ‘Why is Jade so angry and sad?’ Over and over again, just when I thought I knew what Jones was up to, he ingeniously anticipated and shot down my suspicions. Meanwhile, the novel stretches the boundaries of the horror genre, its whole first half a slow burn that tricks the reader into investing deeply in Jade herself … If My Heart Is a Chainsaw has a weakness, it’s that Jones peels off so many layers of assumption and cliché that by the time the bloody bill of the slasher plot comes due, as it must, the climax feels a bit rushed … Jones brings the novel to a close with a reveal that knits his themes together beautifully, but perhaps he underestimates how much readers will have invested in Jade and the people he’s surrounded her with, as well as how deeply the slasher’s blows cut when they finally come.”

–Laura Miller on Stephen Graham Jones’ My Heart is a Chainsaw (Slate)

“D.H. Lawrence understood early on that his calling was to divide readers and friends. He hated to be silenced but loved to be hated … Wilson is fully alive to his faults. This is a writer, she argues, who didn’t ask us to agree with him. He asked us to be stimulated, delighted, and outraged by turns … He knew as he was writing Lady Chatterley’s Lover that it couldn’t be published. The anathemas added to his allure and became part of his own powerful vision of himself, captivating and enraging readers … This is a bold, fervent contribution to Lawrence studies, full of spirit and insight and enviably agile prose. It’s a fitting response to Lawrence’s embattledness, which arguably necessitates extreme investment and speculative volatility. It’s impossible to do him justice, so it’s better to go for a high-energy caper instead. One result of this is that Wilson propels herself into some loopy judgments … Her book is an enthralling and eccentric friend of a book (it’s appropriate that Lawrence’s friendships were as out of control as they were energizing), much more fun as a read than traditional biographies with more measured judgments. Compared with so many other versions of Lawrence, Wilson’s book offers rich ambivalence toward its subject, in place of a stark binary.”

–Lara Feigel on Frances Wilson’s Burning Man: The Trials of D. H. Lawrence (The New Republic)

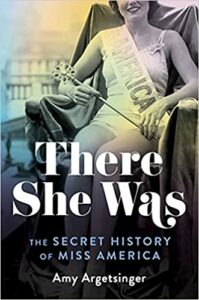

“The story of Miss America is in fact two stories: one about a cultural behemoth that for decades seemed to actually represent something about womanhood and America, and the other about a weird, passionate subculture defiantly clinging to its tarnished crown … Argetsinger conjures the shallow, spangled drama of state pageants—You’ll never believe what happened next!—without judging or sneering. But a certain sadness and strangeness still cling like hairspray to the whole process … The more the pageant’s glitzy, cheesy heart is dissected, it seems, the harder the whole thing is to hold together. (A cynic might wonder if a better way for America to support young women would be to simply fund their education, instead of tossing out scholarships based on their skill at belting out Barbra Streisand numbers.) As Miss America struts, or stumbles, to its centennial, in September, the pageant’s declining audience has prompted big questions about its meaning, relevance, and future. Argetsinger’s upbeat approach skirts the existential hand-wringing to focus instead on the stories of the contestants. Her sympathetic ear brings forth candid, conflicted testimony from an array of former and almost Miss Americas, and she emphasizes the sisterhood and support that many of the women found—often years later—among other winners. Other books have grappled more deeply with the power structures and cultural impact of the pageant, but few have done such a lively, clear-eyed job at evoking its pleasures.”

–Joanna Scutts on Amy Argetsinger’s There She Was: The Secret History of Miss America (AirMail)