Our trove of tasty reviews this week includes Jennifer Wilson on Alexandra Kleeman’s Something New Under the Sun, Rosa Boshier on Anthony Veasna So’s Afterparties, James Lasdun on Stephen King’s Billy Summers, Patricia Lockwood on Marian Engel’s Bear, and Danzy Senna on Robin DiAngelo’s Nice Racism and Courtney E. Martin’s Learning in Public.

“Kleeman takes the water wars of Roman Polanski’s Chinatown and updates them for our era of severe droughts and unending wildfires, giving us a slick neo-noir where the central crime is neither murder nor blackmail but climate change … As global warming makes a mockery of our timescales for dystopia, this novel is a reminder that, pretty soon, we will not have a choice between real things and whatever approximations of them will exist on a ruined planet. While Kleeman’s dark humor makes this pill a little easier to swallow, you are still left wondering: What was that I just drank? … Few writers are more committed to exposing the ridiculousness of everyday consumption … As the secrets surrounding the liquid start to unravel, the mystery element of the novel begins to feel a bit … damp. In the end, the story behind the conspiracy is surprisingly mundane, especially given the book’s hyperreality and intricate imagery. This mundanity also seems to be Kleeman’s point. Is there really such a thing as a shocking twist under capitalism?”

–Jennifer Wilson on Alexandra Kleeman’s Something New Under the Sun (Vulture)

“A deceptively simple narrative structure scaffolded by social commentary and humor. Equal parts absurd and empathetic, Afterparties probes the complex lives of California Cambodian Americans in a style So once described as ‘post-khmer genocide queer stoner fiction’ … So’s writing insists that ancestral haunting and millennial snark can exist simultaneously. Parts of Afterpartiesread like critical race theory … Others, like a text chain between friends … Wise to the familiar 21st century tropes of technological skepticism and potential, it is hard not to label So a voice of his generation. His humor feels straight out of millennial media darlings like Broad City, Insecure or Atlanta, but his themes are decidedly deep, such as the impact of inherited trauma, how it gets lodged into the corners of how we love and work. And his subjects are often overlooked … Unlike authors of most contemporary cultural trauma narratives, So doesn’t linger in a diasporic longing, the need to excavate one’s family’s past, mining it for meaning in the present. Instead, he blends this second-generation need-to-know with insight and, as So’s former agent Rob McQuilkin put it, ‘survivor’s wit’ … It is this ability to make pain shape-shift into the hopeful and the hilarious that makes So’s work so compelling … So’s stories allow the past to well up into the present without force or preciousness. Afterparties insists on a prismatic understanding of Cambodian American diaspora through stories that burst with as much compassion as comedy, making us laugh just when we’re on the verge of crying.”

–Rosa Boshier on Anthony Veasna So’s Afterparties (The Washington Post)

“… clearly the work of a writer in retrospective mood: taking stock, paying his dues … A lot of writerly angst seems encoded in all this; lingering pique, perhaps, from ancient debates about the literary merits of King’s hugely popular fiction…It certainly makes for an interestingly complicated subtext, which is soon matched by the text itself as Billy starts planning his own counterscheme for getting out alive (and getting paid) … there’s something at once prudish and prurient about the ensuing relationship that’s hard to take. Post #MeToo, the conventional sexual dynamics of the pairing obviously wouldn’t work, and King tries hard to square them with those of our own moment, keeping things chaste while also keeping sex very much to the fore. The result is a weird sort of latter-day Hays Code effect, all separate bedrooms and nobly resisted temptation, offset by graphic anatomy shots and regular moments of accidental intimacy … That these significant flaws don’t totally derail the book is a testament to its author’s undimmed energy and confidence. His eye for detail, especially at the dreckier end of roadside culture, is sharp enough to keep the long car rides that crisscross the novel lively and vivid, and he remains in possession of a seemingly effortless verbal flow that surges on over bumps and banalities in the story line (must the bad guy always turn out to be a pedophile?) without letting up. But next to classics of the One Last Job novel and its close variants…it seems driven more by formula, in the end, than the real reckoning with fate and mortality that the genre, at its best, affords.”

–James Lasdun on Stephen King’s Billy Summers (The New York Times Book Review)

“Who hasn’t let a bear go down on her off some crazed librarian’s high? A numerical system cannot be imposed on the bear, but the compass can: she swings him south … The risk in sex, or what your body feels to be the risk, is that you will die in someone – more possible with a bear than a person. The body must feel it as a risk because it must also feel caught at the end of its fall. But here this exchange is made actual: he lays her open and he could go further, he could make her a long jet of blood that would fall forever without a net. But she puts her hand up against the ultimate, she will not let him take her all the way … The book has the shape of a fable, but the soul of a real encounter: friction and fire, drunkenness and peanut butter, the clash of two solitudes which cannot be made one. Yet the essential gift of the fairy tale is retained. Lou leaves the island equipped with what she needs, the breath of kind beasts upon her … People like Engel write books not to shock society but to free themselves, to violate some inner constraint that makes the agreed on forms of living unbearable … Bear was her book of freedom. As a writer, you are lucky to manage one novel that strips away your obstructive tendencies, that sets you out in the sun and makes a long lean jerky of you.”

–Patricia Lockwood on Marian Engel’s Bear (London Review of Books)

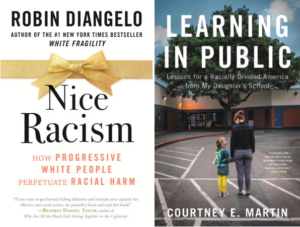

“DiAngelo diagnosed what has never not been obvious to Black people (to be Black in America is to hold a Ph.D. in whiteness, whether you want to or not): that white people, when their ‘expectations for racial comfort’ get violated, go into a defensive crouch, and vent some blend of guilt, anger, and denial. White privilege turns out to be a kind of addiction, and when you take it away from people, even a little bit, they respond just like any other addict coming off a drug. The upper-middle-class thin-skinned liberals among them are also very willing to pay for treatment, of which DiAngelo offers a booster dose in a new book, Nice Racism: How Progressive White People Perpetuate Racial Harm, aware that the moment is ripe … The word brave gets used a lot in [Courtney E.] Martin’s book, and the idea of bravery gets performed a lot in DiAngelo’s book, as she time and again steps in as savior to her Black friends, who apparently need a bold white person to take over the wearisome task of educating unselfaware, well-meaning white people. In a curated space and for an ample fee, she heroically takes on a job that Black people have been doing for free in workplaces and at schools and in relationships over the centuries … How we have wished that white people would leave us out of their self-preoccupied, ham-fisted, kindergarten-level discussions of race. But be careful what you wish for. To anyone who has been conscious of race for a lifetime, these books can’t help feeling less brave than curiously backward … Martin’s impulse to idealize Black people as fonts of needed wisdom has a counterpoint: She can’t seem to help pathologizing Black people as victims awaiting rescue…Martin just can’t shake her patronizing belief that Black people need her to save them … The world these writers evoke is one in which white people remain the center of the story and Black people are at the margins, poor, stiff, and dignified, with little better to do than open their homes and hearts to white women on journeys to racial self-awareness.”

–Danzy Senna on Robin DiAngelo’s Nice Racism and Courtney E. Martin’s Learning in Public (The Atlantic)