Our stable of superlative reviews this week includes Jia Tolentino on Elizabeth Gilbert’s All the Way to the River, Megan Nolan on Eimear McBride’s The City Changes Its Face, Beejay Silcox on R.F. Kuang’s Katabasis, Joshua Hammer on Phoebe Greenwood’s Vulture, and Dan Piepenbring on Kate Zambreno’s Animal Stories.

“In time, Gilbert becomes a twisted bedside nurse, tying off the arms of a ‘venomous junkie’ who has already lived nine months longer than the doctors thought she would. And yet this off-kilter enabler remains Elizabeth Gilbert, a woman who could, in under thirty seconds, locate transcendent human insight in a nuclear-waste dump. She tells herself, ‘Rayya is my most beautiful story.’ Then, losing the faith, she decides to murder Rayya, literally, by switching her morphine pills with sleeping pills and covering her in fentanyl patches—a plot that fails only because Rayya somewhat demonically cottons on to the plan and thwarts it. Gilbert realizes that she has hit rock bottom, that she is a sex-and-love addict—an addict all around, actually. This becomes the organizing principle and revelation of the book: Gilbert’s journey with Rayya is merely an extreme version of a dynamic that ‘all of us’ can relate to, Gilbert tells her readers, because, like addicts, we have all grasped desperately at ‘relief from the sting of life.’

I’m not sure that’s true. I’m also not sure that it needs to be. Those who follow Gilbert on social media will know the broad outlines of the Rayya story, but the most dire moments in the memoir were not previously public, and those moments make the book’s self-help framework seem both unnecessary—who could possibly stop reading this?—and wildly mismatched. Gilbert is funnier and more self-aware than the public image of her, a fate not unusual for women writers. But the funniest line in the book is one that was not meant to get laughs: ‘Even if your wheels have never fully come off, I suspect, at some level, that I might be you, and that you might be me, and that all of us might be Rayya.’ The Eat, Pray, Love paradigm always rested on the premise that Gilbert, a woman who is profoundly and obviously exceptional, could function as a blueprint for the ordinary woman. This notion may have finally reached its end point.

…

“Gilbert has always made hay from her own blind spots and ludicrous proclivities. Much of her writing ends on a note of hope that she might have run her most tempestuous tendencies ragged, and can perhaps start anew. All the Way to the River ends with her narrowly avoiding another sexual and romantic relapse—but, this time, Gilbert doesn’t gesture toward the idea of moving on, or of being changed. Not exactly. She is, she writes, always walking on the precipice. It’s the language of recovery, an approach of total humility, the recognition of a fundamental fallibility which does allow so many people to finally, actually live.”

–Jia Tolentino on Elizabeth Gilbert’s All the Way to the River (The New Yorker)

“Responses to Eimear McBride’s work—whether rapturous or puzzled—often begin by considering her formal innovations. The story of her success is a heartening one. An odd, seemingly unsellable book, A Girl Is a Half-Formed Thing, for which McBride took nine years to find a publisher, jolted to remarkable literary heights in 2013 thanks to several prizes and sparkling reviews. Her daring prose style was part of what made her success so cheering: evidence that the reading public is still eager for a novel that not only comforts or entertains but challenges and uproots expectations. Hers is prose in which sentences judder and disintegrate and run over each other.

…

“What is perhaps most surprising about The City Changes Its Face is how little its unconventional style intrudes on its narrative. Often, such unorthodox registers continually announce themselves, the reader always conscious of their alien presence. Here, though, McBride’s genius is to create a work whose innovation allows the reader to experience the sensation of feeling and thinking, instead of observing thoughts and feelings described. The sentences do not show themselves off, are not self-conscious of their strangeness.

…

“There is nobody alive writing sex like this. McBride is able to capture the often indistinguishable line between agony and pleasure, the way one can be known totally and known not at all from one moment to the next. I read this book in the flayed aftermath of a break-up, still in that state where it seems unlikely that I’ll ever touch anyone again. The execution of these scenes was so powerful that it felt as if they were recalling painful memories of my own, instead of those belonging to fictional characters. What a glorious achievement, to make life instead of merely describing it.”

–Megan Nolan on Eimear McBride’s The City Changes Its Face (The New Statesman)

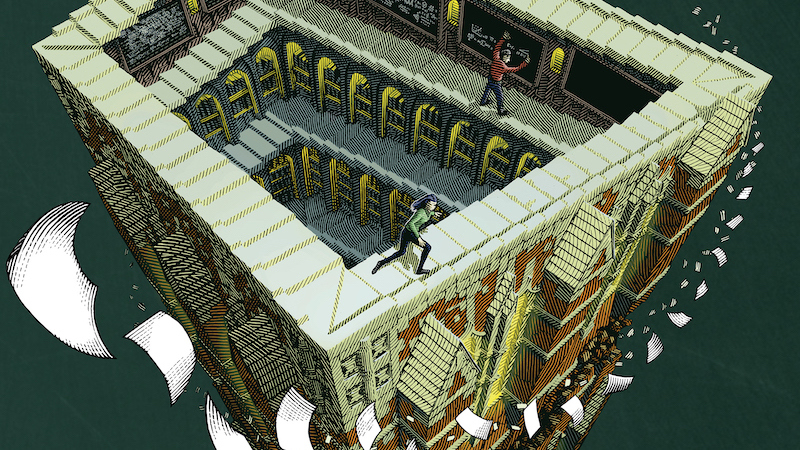

“The more academia has broken your heart, the more you’ll love RF Kuang’s new novel. Katabasis knows the slow grind of postgrad precarity: the endless grant grubbing and essay marking; the thesis chapters drafted, redrafted and quietly ignored by a supervisor who can’t be bothered to read—let alone reply to—an email. Living semester to semester, pay shrinking, workload metastasising, cannon fodder in a departmental forever war. Katabasis knows how it feels to spend your best thinking years doing grunt work to further someone else’s ideas, clinging to the bottom rung of a ladder you will never be allowed to climb: less an ivory tower than a pyramid scheme. Academia is a hellscape; Katabasis just makes it literal.

…

“Kuang isn’t subtle. She doesn’t allude; she indicts. Some structures are so intractable, she argues—so insidiously self-replicating—they can only be disrupted with blunt force. But she also knows that a joke can deliver the same hard clarity as rage; sometimes more. She doesn’t pull her punches, or her punchlines.

…

“Scathing about the institution, faithful to the ideal: Kuang is a campus novelist to the core. Katabasis is a celebration of ‘the acrobatics of thought.’ A tale of poets and storytellers, thinkers and theorists, art-makers and cultural sorcerers. It jostles with in-jokes, from the Nash equilibrium to Escher’s impossible staircase; Lacan to Lembas bread. This is a novel that believes in ideas—just not the cages we build for them.”

–Beejay Silcox on R.F. Kuang’s Katabasis (The Guardian)

“In the early 2000s, the go-to destination for the Western media in Gaza was the Al Deira Hotel, opened during the brief period of optimism that followed the Oslo Accords. An Ottoman-style palace by the sea, the establishment offered a five-star refuge from the missile and drone strikes just outside its walls. During one reporting trip to Gaza in April 2004, I shuttled from the scene of a targeted assassination—mangled car, remains of a Hamas leader—to Al Deira’s beachfront restaurant, where I dined on hummus and fresh shrimp as the sun set over the Mediterranean.

Phoebe Greenwood’s novel, Vulture, conjures up this world with mordant humor and breathtaking immediacy. A Jerusalem-based stringer for British newspapers between 2010 and 2013, and later an editor and correspondent for The Guardian, Greenwood sets much of her story at a Gaza City hotel called the Beach, an unmistakable stand-in for Al Deira.

…

“Greenwood deftly portrays Byrne’s downward spiral, though some of her touches don’t quite work. Little Jihad, the creepy son of the one-eyed room cleaner, lurks in the hotel shadows, spying on Byrne; when she finally gets him to speak, he delivers soliloquies in perfect English about Charles Dickens and The Bold and the Beautiful. And frequent appearances by a pigeon that perches on her windowsill like a Greek chorus, mocking her self-abasement and growing detachment from reality, seem a tad heavy-handed.

The devastating consequences of Byrne’s recklessness foreshadow the apocalypse unfolding in contemporary Gaza. One resident offers a stinging rebuke to the journalists who stake their careers on tragedy. ‘You come, you watch us die, you watch us grieve, take our stories, go home,’ she tells Byrne. ‘Do you help? No. My husband cleans your sheets. You kill his family.’ Today, international journalists are largely barred from Gaza, and their luxurious refuge from the dying and grieving has disappeared. Early last year, I.D.F. bombs struck Al Deira, leaving the hotel, like almost all of Gaza, a mound of rubble.”

–Joshua Hammer on Phoebe Greenwood’s Vulture (The New York Times Book Review)

“Nabokov was stirred to action by suffering. Sometime in 1939 or 1940, he came across ‘a newspaper story about an ape in the Jardin des Plantes,’ he wrote, ‘who, after months of coaxing by a scientist, produced the first drawing ever charcoaled by an animal: this sketch showed the bars of the poor creature’s cage.’ Scholars have never found that newspaper, but Nabokov says it led him to begin writing Lolita. Where some give to PETA, others invent Humbert Humbert.

Kate Zambreno’s Animal Stories, the newest installment in the publisher’s Undelivered Lectures series, relates Nabokov’s anecdote as part of a searching, charmingly discursive meditation on zoos. For Zambreno, these are sites of yearning, boredom, and despair, which is not to say they lack wonder. They’re places where parents, watching their children watch the animals, try to reach through the bars and touch their own childhoods, which scamper away.

…

“Zambreno’s reveries flit between criticism, history, and memoir—an approach well-suited to the diffuse melancholy of the zoo. (The second half of Animal Stories,an essay about Kafka’s ‘identification with the nonhuman,’ lacks the immediacy of the zoo piece, though it includes a memorable episode in which Zambreno teaches The Metamorphosis over Zoom, the unstable internet connection reproducing the conditions of Gregor Samsa’s alienation.) Reading about Jumbo the elephant, who once shattered his tusks in rage and whose night terrors could only be assuaged by whiskey, made me remember the time I watched circus elephants march across 34th Street in the dead of night—something they used to do every year en route to Madison Square Garden—one elephant’s trunk gripping another’s tail, as if they were afraid of getting lost. I thought of how ridiculous it is that LBJ called his penis ‘Jumbo,’ and that he once exposed himself to a group of reporters who’d asked why the United States was in Vietnam: ‘This is why!'”

–Dan Piepenbring on Kate Zambreno’s Animal Stories (Harper’s)