Our bounty of brilliant reviews this week includes Hua Hsu on Anthony Veasna So’s Afterparties, Alan Cumming on James Lapine’s Putting it Together, Jo Livingstone on The Letters of Shirley Jackson, Raina Lipsitz on Ross Barkan’s The Prince, and Katy Waldman on Katie Kitamura’s Intimacies.

“[A] remarkable début collection … The history of Asian American literature is one driven by a hunger for language. Classics of immigrant storytelling can often feel sparse and solemn, as characters grasp for phrases and expressions to capture the paradoxes that define their lives. So seems conscious that his work will be slotted into this broader tradition…even if Cambodians are often marginalized as ‘the off-brand Asians with dark skin’ … So is hardly given to stoic silences. The young people in Afterparties spill forth with language … Immigrant stories often traffic in themes of sacrifice and intergenerational strife, where the past is meaningful only as an obligation, or a set of traumas, to be silently shouldered. But the children of Afterparties seek something different … It feels transgressive that Afterparties is so funny, so irreverent, concerning the previous generation’s tragedy … His sentences are brusque and punchy, and there’s an outrageous, slapstick quality to his scenes. But the stories often end on a haunting note, resonating with the broader consequences of leaving or staying.”

–Hua Hsu on Anthony Veasna So’s Afterparties (The New Yorker)

“…not so much a book at all, but a post-mortem, a forensic investigation into what surely must be one of the most unlikely and chaotic journeys to a Pulitzer Prize and a place in the highest echelons of the American musical theater canon. There are some interjections and explanations by the author, but its majority content is transcribed testimony from a vast array of the people who were part of its faltering progress toward a Broadway opening, and who reveal with increasing frankness just what a dark and troubled path it was … I must admit to having slight dread that this was going to be the literary equivalent of the many masturbatory galas honoring Sondheim I have attended—and occasionally performed in—over the years. Yes, he’s a genius, yes there’s no one like him, yes we aren’t worthy. I can’t imagine how bored he must be of that form of blind adulation, especially when his work seems to promote its antithesis, with many of his characters seeming to squirm and shrivel when they are feted, and look inward, or to bigger ideals than self-glory. But soon things gallop apace … But despite these and many other hilarious musical theater geeky gems, this is not a collection of gossip. It is actually a story of artistic steadfastness, revealing as much about the ultimate work as the experience the participants endured while making it.”

–Alan Cumming on James Lapine’s Putting it Together: How Stephen Sondheim and I Created Sunday in the Park With George (The New York Times Book Review)

“… the letters are startlingly vivacious and emphasize her gift for invention, which she used to transform ordinary people and events into magic … Hyman comes across as petty and cruel, a man who couldn’t remain faithful and also couldn’t seem to forgive the fact it made Jackson unhappy … Yet Jackson’s descriptions of his antics in her own letters to friends are cutting. She’s so funny that the misery he causes seems to burn off like mist on a hot lawn … Jackson’s letters are stuffed with wisecracks and little sketches of Hyman looking stupid … While she makes light of her obnoxious husband, the letters also show her talent for imbuing the innocuous with malign or mysterious intentions. She seems to have been drawn to the macabre throughout her life, but it was as an adult, ensconced in domesticity, that her feel for the gothic intensified and grew more inventive … The Letters of Shirley Jackson is a glimpse into one of literature’s most contested personal lives and the bargains she struck in order to live it.”

–Jo Livingstone on The Letters of Shirley Jackson (The New Republic)

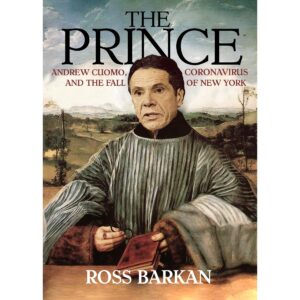

“A man considered a national savior by many less than a year ago, Andrew Cuomo is now hanging on to his political career by his fingernails … Over the years, Cuomo has obsessively cultivated an image as a pragmatic progressive who gets things done. Barkan demonstrates that the governor, never a committed ideologue, has been far more pragmatic about building his brand than executing a progressive agenda … Though more willing to embrace a practical expediency, the younger Cuomo lacked his father’s charm and ostensible commitment to principle. Whereas Mario was loved as a statesman and orator, Andrew was grudgingly respected for his ruthlessness and bullying … Although his inability to inspire genuine warmth has to some extent checked Cuomo’s ambitions, he has compensated with brute force and cold cunning. Unlike his father, Barkan suggests, he seems to have decided it is better to gain the world, regardless of the potential cost to his soul … The Prince is a swift and devastating read. Barkan writes fluently, marshals facts persuasively, and foregrounds the power-obsessed Cuomo’s contempt for the powerless: poor people, incarcerated people, those without the means to write a check or advance a career.”

–Raina Lipsitz on Ross Barkan’s The Prince: Andrew Cuomo, Coronavirus, and the Fall of New York (The Nation)

“There is something decidedly unintimate about calling a novel Intimacies. The refusal to specify (what, whose) feels like a hedge. And yet Intimacies, by the author Katie Kitamura, achieves a kind of truth in advertising. Kitamura pursues various definitions of the word: knowledge of, closeness with, closeness to … The result is a rich, novelistic portrait of an abstraction … The woman’s affect is also the novel’s: haunted, unstable, and intermittently hopeful … Intimacies is not a shallow novel, but it is, finally, a deep and layered novel about superficiality … But the implications of the moment run deeper: in exposing the pneumatics of charm, Kitamura insists that there are motivations behind it.”

–Katy Waldman on Katie Kitamura’s Intimacies (The New Yorker)