Our quintet of quality reviews this week includes Kaveh Akbar on Michael Clune’s Pan, Katie Kitamura on Yuko Tsushima’s Wildcat Dome, Pratinav Anil on Thomas Chatterton Williams’ Summer of Our Discontent, Andrew Martin on John Gregory Dunne’s Vegas, and Margaret Talbot on Sarah Gold McBride’s Whiskerology.

“This is the rhythm of Michael Clune’s first novel, Pan—a steady oscillation between deliciously observed, ferociously strange fragments of consciousness and the social kabuki of the tragicomic teenage bildungsroman.

…

“Nicholas’s stoner-savant voice (‘Bach is like math class for feelings’) sometimes swerves into a register well beyond any teenager’s (‘As the days passed, my consciousness developed a queer economy’). This can be jarring, especially since Clune has so elegantly set up a narrative playground where we can reasonably believe Nicholas is stumbling into Bach, Baudelaire, Camus and Wilde. Reading his experience of these raptures is invigorating and often hilarious. It’s not all high art either; Nicholas and Sarah love Boston’s ‘More Than a Feeling’ with an effervescent lack of irony.

There are a handful of instances, however, when readers may feel the snag of Wait a minute, that’s not Nicholas talking—that’s Michael Clune. I was reminded of Robert Hayden’s poem ‘Those Winter Sundays,’ in which we feel the presence of a fully mature author in a scene taking place in his youth. The tacit temporal delta allows the author an idiom (‘love’s austere and lonely offices’) that he wouldn’t have had at such a young age.

…

“Clune understands that at any given stage of our lives, we are yoked to unprecedented subjectivities. Nicholas can’t experience suffering outside his own any more than I can experience the pain of childbirth right now. This means compassion is a function of imagination, and watching Nicholas’s empathy come robustly alive and calibrate itself against his panic and his parents’ divorce, against art and friendship and sex, is thrilling.”

–Kaveh Akbar on Michael Clune’s Pan (The New York Times Book Review)

“…an ambitious, at times magisterial, epic. Maximalist in tone and structure, it traverses whole swaths of twentieth-century history, from Japanese imperialism and wartime defeat to contemporary ecological disaster. But where much historical fiction is concerned with placing individual characters within the frame of a larger social context, Wildcat Dome does something different: it moves beyond the linearity of history; beyond psychological interiority; beyond even the realm of the human.

…

“Where the apartment’s open window in Territory of Light draws attention to the narrator’s interiority…Wildcat Dome steps through that window—or indeed, the damaged door—and into the world. But it hovers near the threshold between the “rather trivial, personal event” (however violent or traumatic) and events of historical significance. On the one hand, it encompasses many decades of history and sends its characters around the globe—from Japan to America, Europe, and elsewhere in Asia. On the other, it is an intimate story about a trio of social outcasts who witness a crime, the shadow of which they are unable to outrun.

What makes the novel both vivid and idiosyncratic is the way that Tsushima refuses to bridge this gap through the conventional tools of historical fiction, through the rendering of a holistic narrative arc and world. Instead, Wildcat Dome remains distinctly unruly in form. The novel skips through time, employing reminiscence and flashback, the intercutting of timelines, layering and simultaneity as the characters are drawn back into the past, to the question of what they saw, and what they did—and did not—do.

…

“omewhat surprisingly, the novel I thought of as I read Wildcat Dome was Salman Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children. Rushdie’s novel, with its audacious, genre-defining magical realism, might seem an unlikely reference. But Wildcat Dome is a novel that teems with ghosts and phantom voices, and also uses its highly symbolic characters to navigate a critical period in the history of a nation. The distinction between the two is that Tsushima deploys the more fantastical elements of her story not in order to negotiate historical chronology, but to undo it.”

–Katie Kitamura on Yuko Tsushima’s Wildcat Dome (Harper’s)

“Williams’s grand subject being himself, now we have a third memoir. Summer of Our Discontent takes a caustic look at Black Lives Matter from the lofty vantage point of his Parisian garret. At the outset, he tells us that the self-preening, race-mad identity politics of left-leaning liberals has fostered atomisation and precluded solidarity. As a consequence, the illiberal, unhinged right, now united behind Trump, has stolen a march on them. But from this not unreasonable edifice, Williams throws up a enormous scaffolding of enemies, which comes to encompass anyone and everyone engaging in some form or another of collective action. Ultimately, by the end, it appears that Williams’s beef is not so much with Trump as with his leftwing critics.

This is a strange, muddled book. On the one hand, Williams emphasises the primacy of class over race in the US. George Floyd, he says, was not your average African American: he was poor, unemployed, and had a criminal record. Horrific as his killing by a white policeman was, it was unduly racialised by BLM. Fewer than 25 unarmed black civilians are killed by police annually. Most black people will never find themselves in Floyd’s shoes, Williams contends.

…

“He concludes by suggesting that the left and right are just as odious as one another. The storming of the Capitol in 2021, he says, had a mimetic quality, the populist right ‘aping’ the ‘flamboyant reflex’ of the unruly left. With such invidious comparisons, and with such a dim view of collective action, Williams is unable to make the case as to how precisely his homeland is to move towards a post-racial utopia. Excelling in sending up bien-pensant opinion, he has no answers. Fixated on slagging off the left, he has marooned himself on an island of vacuity. So when he articulates a positive vision of the future, all he offers are new age nostrums such as ‘reinvestment in lived community’ and ‘truth, excellence, plain-old unqualified justice.'”

–Pratinav Anil on Thomas Chatterton Williams’ Summer of Our Discontent (The Guardian)

“Despite the overlap in life experience and subject matter, Dunne’s voice on the page is worlds away from Didion’s—gregarious where she is laconic, coarse where she is prim, insecure where she is miles above worrying about the opinions of other humans. Compare her legendary response to an aggrieved letter to the editor—’Oh, wow’— to Dunne’s many-thousand-word essay ‘Critical,’ recounting various slights in print against him and Didion.

…

In her perceptive introduction to a new edition of Dunne’s 1974 book Vegas: A Memoir of a Dark Season, Stephanie Danler begins a sentence about his career with the devastating clause ‘Though largely unread today …’ While true, one imagines this would have particularly stung a writer who depicted himself wondering, early in this account, whether his death would merit a write-up in Time magazine. (Speaking of largely unread today …) Dunne is at his best when overriding his hangups and explaining how things work, whether it be the teeth-grinding process of drafting a Hollywood screenplay, in his book Monster, or his pieces on sports, Los Angeles, politics and much else for The New York Review of Books.

…

“To a contemporary reader, Dunne’s lack of a hook—an angle, as the Vegas denizens he encounters might call it—is more striking than the genre agnosticism signaled by having ‘memoir’ in the subtitle. (A helpful designation for a book that is ‘both real and imagined’: fiction.) To an impressive degree, Dunne fails to find much in the way of the salvation he’s looking for, or even drama, even when he finds himself set up for a sexual encounter with a 19-year-old named Teddi and decides to call his wife for advice. ‘It’s research,’ Didion tells him. ‘You’re missing the story if you don’t meet her.’ He meets her, but thanks to his condescension (‘You ever read Gatsby?’) doesn’t get much of a story.

Vegas is all drift and repetition, a chronicle of killing time in an ugly, infernally hot place full of desperate liars. Dunne encounters terrible taste of every conceivable variety, from wall-to-wall homophobia and racism—mostly reported, but striking in the volume of what the author deems worthy of passing on—to lousy food, drinks, clothes and people. ‘I needed to feed on some fantasies of my own,’ Dunne writes in a typical passage, ‘anything to erase the grotesqueries of the evening.’ It’s the best vaccination against 1970s nostalgia I’ve ever received. Compared with this, Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas reads as a colorful salute to a great American city.”

–Andrew Martin on John Gregory Dunne’s Vegas: A Memoir of a Dark Season (The New York Times Book Review)

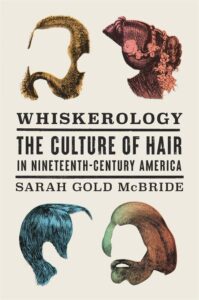

“Despite its whimsical title, Whiskerology is a serious academic book with many points to make about race and gender and their entanglement with coiffure in the United States. But McBride doesn’t shy from delightful anecdotes for those who like to magpie through history’s weirdnesses alongside its grave themes.

…

“McBride traces hair’s cultural meaning through history. In medieval Europe through to the eighteenth century, people saw it as separate from the body—a substance extruded like, regrettably, excrement. By the eighteenth century, this theory was replaced by a view of hair as an ornament that signaled both aesthetics and social position…In the nineteenth century, the period that McBride focusses on, hair was framed as an intrinsic biological feature that revealed fundamental truths. Even a single strand could supposedly expose someone’s race or criminality.

…

“You might think the beard boom made up for hair’s retreat from the head. Maybe it did, in part. But McBride gives other reasons why, after a century of clean-shavenness, nineteenth-century men embraced whiskers. Beards emerged as legible emblems of male virility and authority just as women began demanding the vote. The beard vogue of the late nineteenth century, McBride notes, was unusual in that it inspired celebratory writing about the whiskers themselves. Pro-beard propaganda included the daft theory, floated by the widely published slavery apologist and physician John Van Evrie, that the ‘Caucasian is really the only bearded race, and this is the most striking mark of its supremacy.’ (Frederick Douglass, splendidly bearded, remarked that Van Evrie must have grown ‘weary of his unprofitable twaddle about the negro’s brain’ to resort to ‘disquisitions upon the beard.’) It’s no coincidence, McBride argues, that the bearded lady became a sideshow staple during this era of male whiskers and women’s-rights activism. The ‘enfreakment’ of women with facial hair, she suggests, helped reinforce the idea that beards—and power—belonged to men. That might be a stretch. Did men really need beards to remind anyone that they were in charge?”

–Margaret Talbot on Sarah Gold McBride’s Whiskerology (The New Yorker)