Our quintet of quality reviews this week includes Alexandra Jacobs on Catherine Lacey’s The Möbius Book, Katy Waldman on James Frey’s Next to Heaven, Lily Meyer on Deborah Baker’s Charlottesville, Dwight Garner one Joe Westmoreland’s Tramps Like Us, and Robin Kaiser-Schatzlein on Bridget Read’s Little Bosses Everywhere.

“There was a time when such narratives were lightning bolts cast down on the world of letters, causing considerable shock waves. (I’m thinking of Catherine Texier’s 1998 Breakup, about the dissolution of her marriage to Joel Rose, and even Rachel Cusk’s 2012 divorce memoir Aftermath.) But Lacey isn’t scorching earth—she’s sifting it, flinging fistfuls of dirt and thought at us.

…

“Lacey runs the same list of acknowledgments and credits at the end of both novella and memoir. There are similar themes, but also an element of ‘Hey, you got your chocolate in my peanut butter!’ in their juxtaposition. The fiction is shorter, noirish and elliptical. Was yoking it to the fiction an organic, creative act—whatever that is, we’re maybe meant to consider—or a clever packaging solution for two not-quite stand-alones?

…

“The Möbius Book invites the reader to consider the overlaps between its two parts, an exercise both frustrating—all that turning back, forth and upside down—and exhilarating, because Lacey is imaginative and whimsical when considering reality, and sees truth in make-believe. The curving strip is like Lewis Carroll’s looking glass. Both halves share a broken teacup. Twins! A violent man. Bursts of sarcastic laughter. A dying dog (God?) with important spiritual wisdom to share. Depending on how you twist, this book—defying the linear story, homage to the messy middle—is either delightfully neo-Dada or utterly maddening. Or, as Lacey puts it: ‘Symbolism is both hollow and solid, a crutch, yes, but what’s so wrong with needing help to get around?'”

–Alexandra Jacobs on Catherine Lacey’s The Möbius Book (The New York Times)

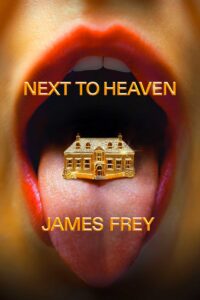

“Is Next to Heaven autofiction? No, it’s a straightforwardly plotted thriller about a group of stratospherically wealthy finance types and their wives behaving badly in the fictional town of New Bethlehem, ‘as beautiful and safe and perfect a town as exists anywhere in the world.’ Is it, for lack of a better term, cancelled-guy fiction, animated by resentment at being misunderstood? That’s a tougher call. Frey wasn’t cancelled for abusing women or being a sex pest—just for embellishing his life—but he appears to identify with the #MeToo discontents and to have adopted the gender politics and postures of that tribe. So the book is provocative in a familiar way.

…

“I have wrestled with a Frey-like dread through the writing of this review—I’m afraid that I’ll describe his book and no one will believe me. The two main characters, Devon and her husband, Billy, are a swarm of status signifiers stuffed ungrammatically into a Burberry trench coat … It’s tempting to imagine that the author’s caressing treatment of so much wealth and hotness and success is, in fact, a slap. Maybe Frey is mocking materialism? But if lines like ‘They got married at the Dallas Country Club in front of eight hundred guests in what Texas magazine called the Wedding of the Decade’ are meant critically, it’s hard to know what, exactly, they’re criticizing. Does Frey intend to take aim at the emptiness of money and status as metrics for the good life, for human flourishing? If that’s the case, the book’s obsession with niche signifiers is so extreme that he seems to be targeting no one but himself. Likewise, the intensely retrograde gender politics—and the text’s out-of-control, onanistic eroticism—seem fairly personal and specific. As satire, Next to Heaven is unintelligible, as though someone is universalizing their own hangups and then skewering them for clout.

Writers of autofiction have been accused of trying to preëmpt criticism by couching their work in self-awareness. That’s not the play here. What preëmpts criticism of Next to Heaven is simply how bad the book is…On the other hand, a goal of autofiction, which often attends closely to small details, is to cultivate exquisite awareness in the reader. And it’s true that, while reading Next to Heaven, I sometimes thought I could feel individual cells in my body trying to die.”

–Katy Waldman on James Frey’s Next to Heaven (The New Yorker)

“The biographer and essayist Deborah Baker’s Charlottesville: An American Story is both an account of those two horrifying days and an intellectual history of the far right in the United States. It mixes investigative rigor—Baker must have listened to hundreds, if not thousands, of hours of archived Charlottesville City Council meetings, as well as far-right podcasts and YouTube videos—with emotional intensity and wide-ranging cultural critique. Baker reaches from Virginia’s slaveholding history to the poet Ezra Pound’s deluded post–World War II fascism to the misogynistic trolls of Gamergate in her quest to understand Unite the Right. The result is not merely smart but shattering. It joins the ranks of some of the best American nonfiction in recent years—Patrick Radden Keefe’s Say Nothing; Sarah Schulman’s Let the Record Show—as testimony to events we’d be unwise to forget.

…

“Charlottesville is not a book of the here and now. It’s too wide-ranging for that. In all its movement through time, through archives and forums and the intellectual history of America’s ugliest movements, it seeks to locate ‘the germ of the present in the past’—a mission of which Baker declares herself skeptical; maybe, she writes, it’s ‘just something writers tell themselves to exert control over events that are effectively beyond their control. But it was what I knew.’ It’s also a way of looking into the future.

…

“Charlottesville tells us how the country got here: by kowtowing to guns, by refusing to accept responsibility for racism close to home, by too many people ignoring what they don’t want to see and not taking seriously what they don’t want to hear. All those decisions—even, or especially, the ones that don’t feel like decisions at all—create room for fascism to flourish, just as Charlottesville’s white supremacists took the town’s foot-dragging on removing the Lee statue as an opening to wave guns and Confederate flags in public parks.”

–Lily Meyer on Deborah Baker’s Charlottesville: An American Story (The New Republic)

“Despite its title, lifted from Bruce Springsteen’s ‘Born to Run’…Tramps Like Us isn’t primarily a music novel. Here’s what it is instead: an epic, moving and ebullient gay road-trip novel, set in the 1970s and early ’80s, that doesn’t have a pretentious bone in its body. It reads like an avid, feverishly detailed letter that the author wrote and mailed directly to readers…

…

“Its reissue is one of this summer’s earliest literary tent poles. A book this perceptive but amiably unpolished, that pops as if in Kodachrome colors, that deals out tablespoons of American simplicity and horniness and delight, might seem like a small thing to look for, but it’s a big thing to find. It made me feel I had my left hand on the wheel of a car, and the right on the radio dial.

…

“Westmoreland kisses one scene off another as if he were shooting pool. But Tramps has a darker edge, provided by its characters’ heavy and sometimes debilitating interest in heroin. When AIDS appears on the scene, it’s an emotional landslide. Nearly everyone we’ve come to know is forced to stare it down.

Tramps Like Us is a young person’s novel, a beautiful one that took me back to a time in my life when I read to learn about the world, before the internet and great television took over much of that job, and I was drawn to rambling souls because I too wanted to (and did) haul out maps and flee my hometown with one uncertain thumb in the air.

It’s an approachable minor classic, one that packs in vastly more life than many more serious novels do. You end up wishing that it existed as a mass-market paperback, so that you could sneak-read it under a desk at school or try to carry it in your back pocket. (You would fail; the book is thick.) It is a novel that tastes life at first hand; it’s a palate cleanser for jaded appetites.”

–Dwight Garner one Joe Westmoreland’s Tramps Like Us (The New York Times)

“…are they massive scams or legitimate endeavors? Bridget Read’s thorough history of the industry, Little Bosses Everywhere: How the Pyramid Scheme Shaped America, bolsters the critics’ position. MLMs, she writes, ‘may constitute one of the most devastating, long-running scams in modern history.’ Her contribution lies in explaining how they’ve been able to do it: through the all-American business traditions of weaseling out of regulation, buying political influence, and exploiting the culture’s belief that every individual is a capitalist success story just waiting to happen.

…

“MLMs, like other religions, underpin their ideology with aggressive legal departments. Beyond their battles with the FTC, Read says, companies like Amway have sued bloggers and online critics (often former MLM participants) into nonexistence and imposed mandatory private arbitration agreements on participants that keep complaints out of public courts and the public eye. But the internet has opened avenues for disgruntled distributors to connect and complain. Anti-MLM threads provide access to what was once a completely atomized group of people (who, furthermore, were told explicitly not to talk to other distributors outside their downlines). But aside from a few self-published books, there was little critical media coverage of MLMs in the 1990s and 2000s. The dam has broken in recent years, if gradually: John Oliver did a thorough segment on MLMs in 2016, and in 2019 there was a fantastic investigative podcast, The Dream, hosted by Jane Marie and Dann Gallucci (followed up by Marie’s 2024 book, Selling the Dream: The Billion Dollar Industry Bankrupting Americans). Each was impressively researched and devastating, and yet they didn’t cause a sea change in public perception. Read’s book is a huge addition to the mix, expertly and carefully walking readers through the history of MLMs and revealing them for what they really are: maybe not so much scams as predatory businesses in the vein of payday lenders, for-profit colleges, and international labor brokers. MLMs have too long operated in the dark, but, for all the light it sheds, Read’s book makes you wonder if the industry has simply grown too large and too powerful to regulate or reform.”

–Robin Kaiser-Schatzlein on Bridget Read’s Little Bosses Everywhere: How the Pyramid Scheme Shaped America (The New Republic)

If you buy books linked on our site, Lit Hub may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.