This week’s five alarm five of fabulous reviews includes Tommy Orange on Gabriel Bump’s Everywhere You Don’t Belong, Dwight Garner on Jenny Offill’s Weather, Michael Dirda on Claude McKay’s Romance in Marseille, Lee Thomas on Lidia Yuknavitch’s Verge, and Peter Biskind on Sam Wasson’s The Big Goodbye.

“It’s the rare book that can achieve an appropriate balance between heaviness and levity, and it’s my favorite kind of novel. In his debut, Everywhere You Don’t Belong, Gabriel Bump pulls this off not just generously but seemingly without effort … Just when the prose teeters on the edge of sentimentality, though, he pulls it back with humor … If I had any problem with the book, it was logistical, related to certain plot points inserted seemingly for convenience, but without organic explanation, or even a simple acknowledgment from our narrator. This kind of quibble is both big and small … Despite this narrative not-so-sleight of hand, Bump’s ending still manages to be unexpected and unromantic, while containing so much love and hope … Most funny things are funny because they’re real, this book included. I mean real, here, as something distinct from realism; his characters feel true to their environment in ways only an author who has known people like this, has lived a life at least adjacent to this one, could write … I also believe we as readers have a responsibility to not only call out problematic examples, but also to honor those doing it right, those of any color who are writing about underrepresented or misrepresented communities, and doing the best of what fiction can do at the same time. Gabriel Bump is doing that, has done that.”

–Tommy Orange on Gabriel Bump’s Everywhere You Don’t Belong (The New York Times Book Review)

“In Weather, Offill is interested in the things we can save and the things we cannot … As with Offill’s last novel, Dept. of Speculation, Weather is written not so much in consecutive paragraphs of narration but in often square blocks of text, each set off by white space, as if they were stanzas. They’re the work of a curator who likes a spare hang. Each paragraph is a little lonely, like a figure in an Edward Hopper painting. These parcels of feeling and intellect drop out one at a time, like packs from a cigarette machine. All the others descend down a slot, awaiting their turn. The effect of this style is to put a pause after every paragraph, to hold it up for a little extra light and a little extra examination, to allow it to linger in the mind … Offill has genuine gifts as a comic novelist. Weather is her most soulful book, as well. Lizzie’s relationship with her brother delivers heartbreak after heartbreak. She’s pretty funny about him, too. ‘”Where did all these hipsters come from?” says my brother in his fleece-lined trucker’s jacket.’ Offill’s humor is saving humor; it’s as if she’s splashing vinegar to deglaze a pan.”

–Dwight Garner on Jenny Offill’s Weather (The New York Times)

“…the book McKay was working on in the early 1930s but abandoned because his friends and advisers deemed it too daring to see print. Today Romance in Marseille seems less shocking than strikingly woke, given that its themes include disability, the full spectrum of sexual preference, radical politics and the subtleties of racial identity … To me, though, Romance in Marseille reflects the 1930s discovery and celebration of outcasts, rogues and criminals, all of them regarded as more vital and passionate than the upright citizens of etiolated bourgeois society. Had McKay’s novel been published when it was first written, it would now look right at home in the proletarian company of William Faulkner’s Sanctuary (1931), Erskine Caldwell’s Tobacco Road (1932), James M. Cain’s noir classic The Postman Always Rings Twice (1934) and even, from certain angles, Nathanael West’s bleak comedy Miss Lonelyhearts (1933).”

–Michael Dirda on Claude McKay’s Romance in Marseille (The Washington Post)

“…it is her realism that shocks the senses … Her stories startle and repulse even as they provoke the reader’s gaze … Yuknavitch writes with realism’s gimlet eye and horror’s racing heart … Yuknavitch grounds her existential questions in the flesh. Her attention to the physical—in particular the human body—defines her aesthetic … Yuknavitch revels in subtext and shows just how much of the world exists in the imagination, the grinding of those powerful, terrible wheels … A writer must invent a new language to throw her reader off-balance; you can see Yuknavitch trying fresh approaches as she goes along … Verge reminds the reader constantly of the fact that even while reading we cannot escape the self, not fully. Yuknavitch expects collaboration. What type of book does this anxious age require? Verge offers an opening gambit, first, see … Verge contains a succession of mirrors, stories that reflect one way, then another. It’s a kind of antidote to the binary of the present moment, when anxiety drives a hunger for either/or. Yuknavitch delivers no answers, but a series of portraits, moments rendered in vivid detail.”

–Lee Thomas on Lidia Yuknavitch’s Verge (The Los Angeles Review of Books)

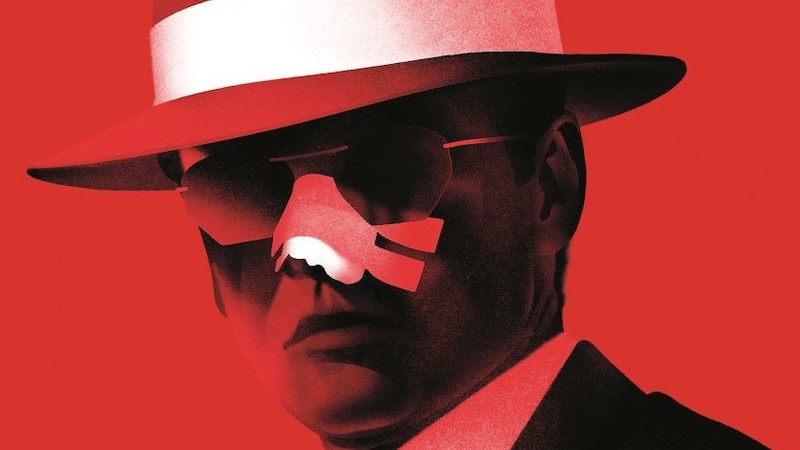

“… fascinating and page-turning … more than a mere biography of a landmark movie; it aims to flesh out the wild and woolly era that incubated it, roughly the late 1960s to the late 1970s, and in this it mostly succeeds … Despite the well-trod terrain, Wasson has flushed so many fresh sources out of the woodwork, and dived so deeply into the voluminous existing interview material, that we barely notice the absence of Towne and Nicholson. Wasson proves himself an indefatigable researcher, plundering every imaginable scrap of relevant material from court record … Wasson’s intensive research has allowed him to create a tapestry so dense with detail that the characters spring to life on the page. Occasionally, however, he forgets the meaning of ‘enough,’ conflating information with trivia and drowning us in more facts than we could possibly want … If this book has a flaw, it is Wasson’s intoxication with his subjects … Nevertheless, in Chinatown, Wasson has found the perfect vehicle for convincingly demonstrating how personal filmmaking in a commercial context, albeit fueled by drugs and worse, enabled the New Hollywood to break the studio mold and reinvent the art of the feature film.”

–Peter Biskind on Sam Wasson’s The Big Goodbye (The Los Angeles Times)