This week’s five alarm fire of fantastic reviews includes Sigrid Nunez on Garth Greenwell’s Cleanness, Parul Sehgal on Machado de Assis’ The Posthumous Memoirs of Brás Cubas, Colm Tóibín on Edoardo Albinati’s The Catholic School, Adam Gopnik on David G. Marwell’s Mengele, and Heller McAlpin on Audur Ava Ólafsdóttir’s Miss Iceland.

“All the same preoccupations found in What Belongs to You—love, desire, abandonment, humiliation, betrayal, self-disgust, disease, shame—reappear in Cleanness, which, if not exactly a sequel, is, Greenwell has acknowledged, part of the same literary project. Some of the stories have been published before, and I have to say that the ones I read at the time they appeared left me somewhat disappointed to see how similar the new work was to the old (according to what I’ve read about the book, I am not the only one to have had such a response). But reading the collection—or lieder cycle—as a whole offers a much different and deeper experience and has dispelled what qualms I might have had, even if I did not find Cleanness as a novel quite the equal of What Belongs to You … the reader is treated to his unfailingly intelligent observations, his acute ability to describe what he sees and thinks and feels. At the heart of these stories lies a desire for radical, even ruthless self-disclosure … For Greenwell, the kinds of sexual encounters he writes about, in which sadomasochism plays an essential part, offer strong possibilities for self-discovery and self-understanding, for liberation and even salvation … None of this would work so well were Greenwell not entirely sincere…There is no irony in Greenwell’s writing, and—for me, regrettably—no comic touch. But one of the things I most admire is the quality of intense earnestness that marks every page. Laying himself bare, putting himself so mercilessly on the line, subjects the protagonist to the risk of appearing self-absorbed, shameful, exhibitionistic, and, of course, ridiculous. But that risk is surely part of the point: it is what makes writing like this worth doing.”

–Sigrid Nunez on Garth Greenwell’s Cleanness (The New York Review of Books)

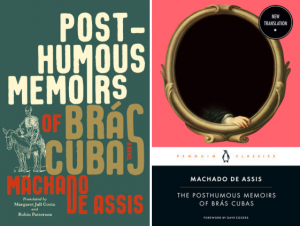

“Is it possible that the most modern, most startlingly avant-garde novel to appear this year was originally published in 1881? This month sees the arrival of two new translations of The Posthumous Memoirs of Brás Cubas, the Brazilian novelist Joaquim Maria Machado de Assis’ masterpiece, a metafictional, metaphysical tale narrated by a man struck dead by pneumonia. Too grim? I neglected to mention that he’s being carried into the afterlife on the back of a voluble and enormous hippopotamus … These two new translations bring another opportunity to enshrine the singular talent and mischief of this writer, whose late novels are insurrections against the novel itself, against its tendencies toward banal realism and earnest piety … He is a writer besotted with the license afforded by fiction. Why not narrate a chapter solely in dialogue stripped of everything but punctuation—provided you can do it well? Why not render one section in ellipses or skip the climax altogether? Read Machado, and much contemporary fiction can suddenly appear painfully corseted and conservative … For a writer with a bottomless bag of tricks, his core achievement is, finally, more humble and infinitely more dazzling than any special effect. It’s not exploring what the novel might be, but looking at people—purely and pitilessly—exactly as they are.”

–Parul Sehgal on Machado de Assis’ The Posthumous Memoirs of Brás Cubas (The New York Times)

“The Catholic School, all 1,268 pages of it, is an effort to explore why boys from such a privileged and settled background would commit such a crime. It pays little attention to the crime itself; we learn hardly anything about the victims other than that they are from a lower class than the perpetrators. Instead, most of the book muses on the meaning of masculinity, on the family and the middle class, on rape, violence, the penis, sadism and masochism, not to speak of morals and manners among Italians of a certain income bracket … Albinati’s book, made up of many short sections, is long and long-winded. It lacks what we might call the literary tone, showing no signs of irony, inwardness, self-consciousness, or ambiguity. Most of the time it is simply garrulous. Reading it is like being buttonholed by a man in a bar who wishes to speak at length about sex and men and rape … What is fascinating about The Catholic School is that it enacts, in the most extreme way, the very sounds some men might have made before they were invited to become more mannerly, more intelligent, more alert, more sensitive, and less stupid. The book was finished in a time when men were often asked to shut up completely and let someone else talk. The Catholic School is, sometimes, a good example of what it was like before this had any real effect. At other times, however, it is a good example of nothing at all, other than the author’s boorishness.”

–Colm Tóibín on Edoardo Albinati’s The Catholic School (The New York Review of Books)

“Marwell’s life has much new to tell us, both about Mengele himself and, more significant, about the social and scientific milieu that allowed him to flourish. There is nothing surprising in educated people doing evil, but it is still amazing to see how fully they construct a rationale to let them do it, piling plausible reason on self-justification, until, like Mengele, they are able to look themselves in the mirror every morning with bright-eyed self-congratulation … The Nazi intelligentsia really believed. An obsessive anatomy and a specialized language of racial difference created an essential intellectual armor, a shield from scrutiny. An alternative intellectual universe was constructed, with its own sciences and academic establishment, to insure that everyone involved would see himself as normal, as a scientist doing science. It was this self-sealing intellectual wholeness that distinguished the Nazis from the commerce-minded conservatives with whom they often allied, and eventually consumed. Mengele’s career is a reminder that Nazism was not, as the left long insisted, capitalism with the gloves off. It was craziness with a white coat on—a faith driven, as most big historical movements are, by passionate ideas, not parsable interests … Crimes committed by the entirety of the Auschwitz staff were ascribed to him. He appears to have been singled out because of the sinister calm and scrupulous care with which he approached the task of sorting out the soon-to-die from the (briefly) saved, a sangfroid that he maintained, as one less confident colleague suggested, because he alone accepted that all of the Jews were already ‘dead upon arrival.’ He was sorting out ghosts, not people.”

–Adam Gopnik on David G. Marwell’s Mengele: Unmasking the “Angel of Death” (The New Yorker)

“I have been on the lookout for books that will transport readers to another time and place. Icelandic novelist and playwright Audur Ava Ólafsdóttir’s atmospheric sixth novel, Miss Iceland, is just the ticket. But be forewarned that another time and place doesn’t necessarily mean a rosier time and place. Set mostly in 1963 in the author’s native Reykjavík—where the weather is cold, windy, and overcast most of the year—this is a subdued but powerful portrait of rampant sexism and homophobia in a society that had yet to open up to women and gays. … Hekla’s visits, bearing library books, boxes of canapés, toys, and adult conversation, are a lifeline for Ísey, just as these mutually supportive friendships are a ray of light in Ólafsdóttir’s novel. But so, too, is Hekla’s unusual voice—reticent but firm, straightforward but wry, melancholic with an undercurrent of irony … [a] quietly mesmerizing, unsettling tale about attempting to rise from the chasms of difficult circumstances by harnessing the power of friendship and creative drive.”

–Heller McAlpin on Audur Ava Ólafsdóttir’s Miss Iceland (NPR)