Our bevy of brilliant reviews this week includes Susan Choi on Austin Kelley’s The Fact Checker, Hamilton Cain on Susan Fraser’s Murderland, Dayna Tortorici on Sophie Gilbert’s Girl on Girl, Fiona Maazel on Torrey Peters’ Stag Dance, and Dwight Garner on Thomas Mallon’s The Very Heart of It.

“These adventures do not, perhaps, make for the most accurate portrayal of the job, but they make for a very enjoyable novel. The Fact Checker is a workplace comedy, a trivia-rich love letter to New York, and, to top it all off, nicely written, which is more of a rare treat these days than it should be. I tore through its lean, witty, plot-heavy pages in just a few hours, on a sun-splashed Sunday afternoon, on my favorite sofa, backgrounded by the Tammy Wynette playlist my ironic teen had programmed in an uncharacteristic attack of sincerity—a foolproof recipe for happiness. So why did I find it so sad—even painful—to read?

…

“Although the inciting incident of The Fact Checker is something suspicious going down at the Greenmarket, the novel is less a mystery than a fleet picaresque. The fact-checker himself, a nice if helplessly pedantic grad-school dropout who’s been single a little too long and drinks a little too much, is less the subject of the story than its tour guide, and what he’s showing us isn’t really The New Yorker or even fact-checking, but New York City before the smartphone. Kelley’s decision to set The Fact Checker in 2004 is his single most impactful novelistic decision. It allows him to make omissions from the story world that, while anachronistic, are unlikely to be noticed by any but a fact-checker: the words Google and internet never appear once in the novel’s 243 pages. Both existed in 2004 and were frequently used by fact-checkers, no less than colored pencils and deskbound landlines. But Kelley’s fudging of this is of a piece with his emphasis on the fact-checker’s extramural adventures.

…

“…so perhaps what I most ached for while reading Kelley’s book wasn’t a simpler world than the one we live in now but a simpler feeling, which Kelley captures exactly: the simple feeling of liking to learn new things, and liking to meet new people who might teach you new things. The simple feeling that ‘known unknowns’ are the right place to start but far from the end of the story.”

–Susan Choi on Austin Kelley’s The Fact Checker (The Yale Review)

“The book’s a meld of true crime, memoir and social commentary, but with a mission: to shock readers into a deeper understanding of the American Nightmare, ecological devastation entwined with senseless sadism. Murderland is not for the faint of heart, yet we can’t look away: Fraser’s writing is that vivid and dynamic.

…

“In Tacoma, 35 miles to the south, Ted Bundy grew up near the American Smelting and Refining Co., which disgorged obscene levels of lead and arsenic into the air while netting millions for the Guggenheim dynasty before its 1986 closure. Bundy is the book’s charismatic centerpiece, a handsome, well-dressed sociopath in shiny patent-leather shoes, flitting from college to college, job to job, corpse to corpse.

…

“While rooted in the New Journalism of Joan Didion and John McPhee, Murderland deploys a mocking tone to draw us in, scattering deadpan jokes among chapters: ‘In 1974 there are at least a half a dozen serial killers operating in Washington. Nobody can see the forest for the trees.’ Fraser delivers a brimstone sermon worthy of a Baptist preacher at a tent revival, raging at plutocrats who ravage those with less (or nothing at all). Her fury blazes beyond balance sheets and into curated spaces of elites. She singles out Roger W. Straus Jr., tony Manhattan publisher, patron of the arts and grandson of Daniel Guggenheim, whose Tacoma smelter may have scrambled Bundy’s brain.

…

“Those beautiful Cézannes and Picassos in the Guggenheim Museum can’t paper over the atrocities; the gilded myths of American optimism, our upward mobility and welcoming shores won’t mask the demons. ‘The furniture of the past is permanent,’ she notes. ‘The cuckoo clock, the Dutch door, the daylight basement—humble horsemen of the domestic Apocalypse. The VWs, parked in the driveway.’ Murderland is a superb and disturbing vivisection of our darkest urges, this summer’s premier nonfiction read.”

–Hamilton Cain on Susan Fraser’s Murderland (The Los Angeles Times)

“Gilbert’s assessment of the era is damning, and likely to resonate with readers of her generation. I came of age in the two-thousands, a few years behind Gilbert, and though I cannot speak for all in my cohort, I can say that certain behaviors were not uncommon. It was not uncommon for girls to starve themselves to be thin, or to wield images of emaciated celebrities as a tool of dietary self-discipline. It was not uncommon to slut-shame other women, to fat-shame other women, to feel the shame of being fat or slutty yourself, or to resort to self-harm to cope with that shame. It was not uncommon to want to be ‘one of the guys,’ but also insanely, impossibly hot, so that all the guys also wanted to sleep with you. (Why settle for one form of male approval when you can have two?) It was not uncommon to laugh at men’s cruel jokes to win their affection, and it was not uncommon to redirect that cruelty toward other women to avoid becoming the target. It was not uncommon to consent to sex you didn’t really want to have, to prioritize a male partner’s sexual experience far above your own, or to pretend to be straight or straighter than you were. And it was not uncommon to do all these things at the expense of literally any other more life-affirming or world-expanding pursuit.

But Gilbert is oddly silent on this pitiful bouquet of pick-me behaviors in Girl on Girl. Though the book is laced with suggestive personal asides and hypothetical questions that gesture at the ill effects of pop culture on young women, it doesn’t include an account of how women actually responded to the material it so assiduously documents.

…

“The removal of the protagonist from this story—the viewer who perceives and acts in response—gives the book an elusive, lopsided quality. On the one hand, it is an exhaustive account, a formidably thorough excavation of pop-cultural artifacts whose disdain toward women is often stunningly blunt. (Terry Richardson’s advice to aspiring models: ‘It’s not who you know, it’s who you blow. I don’t have a hole in my jeans for nothing.’) On the other hand, it is a strangely untethered document, evidence marshalled for an unknown case: a long list of causes in search of a presumed effect. Reading Girl on Girl as a member of its target audience is a conflicting experience, alternately tedious and engrossing, unpleasant and therapeutic. It’s refreshing to be reminded that one does not know history just because one lived through it.

…

“…no amount of sifting through the cultural artifacts of the two-thousands can explain the retrenchment of the Trump era. The story of how Roe v. Wade was overturned is not a story of ideology disseminated from pop culture, let alone of hardcore pornography infecting the mind of the populace; it’s a story about dark money, legal strategy, and the slow, incremental way the anti-abortion movement made the procedure harder and harder to access until conservatives finally hijacked the Supreme Court. In other words, it’s a story about politics.”

–Dayna Tortorici on Sophie Gilbert’s Girl on Girl: How Pop Culture Turned a Generation of Women Against Themselves (The New Yorker)

“It’s never been a good time to be anything other than a white cis male in this country. From there, we might debate which identities and preferences are the most persecuted but can probably agree that now is an especially terrible time for anything that’s not the muscled, racist, and American brand of, say, Joe Rogan. Our self-described ‘king’ of a president (read: the repulsive tyrant half of us voters elected) has made it a priority to oust trans soldiers from the military at a time when recruitment is at an all-time low. Similarly, he has banned trans women from competing in female sports (this sentence alone is enough of an oxymoron to ridicule the order). No doubt these efforts to purge the culture of its humanness are just the beginning.

So it’s a pretty rage-inducing time to be reading and thinking about Torrey Peters’s new book, Stag Dance,which is about trans women in particular and male sexuality in general—the confused and tortured feelings some men have about their birth bodies and ‘masculinity.’ Stag Dance is good in some ways and downright spectacular in others. It’s a collection of three short stories and a novella, and if the effort here is uneven, no matter: the novella alone is such a beautiful, ridiculous, and painful thing, it more than steals the show.

…

“The plot changes, but in many ways, Peters’s interests remain the same. There’s rage and violence, self-loathing and self-sabotage. A leitmotif for this collection is the painful extent to which men in their various stages of denial or transition despise themselves and their feelings and their trans counterparts who feel similarly. In this collection, the hatred radiating toward the trans community from the MAGA right is easily internalized.”

–Fiona Maazel on Torrey Peters’ Stag Dance (Bookforum)

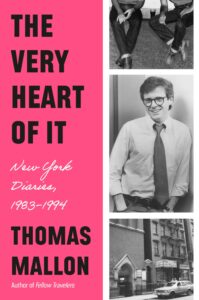

“Is it possible to be kind, sensible, polite, well-adjusted and cheerful, and keep a diary that’s worth anyone’s time? That’s the question that confronts the reader of The Very Heart of It: New York Diaries, 1983-1994, by the gifted but ultra-earnest novelist and critic Thomas Mallon. He’s so nice that he drives me out the window. (In a movie, he’d be played by Matthew Broderick in Izod shirts and tweeds.)

…

“I hung in there with Mallon’s diaries, and they (sort of) softened me up. This isn’t because Mallon cries frequently—upon finishing John Updike’s Rabbit series, upon the death of Richard Nixon, when a man he loves hasn’t called, when he’s had a bad review—but because his diaries capture the youthful mood of a certain period in New York City, because he’s a careful observer and because his naïveté is sometimes winning, in the manner of a pensive number in a Sondheim musical about a new kid in town. Every writer probably needs a bit of this quality to see the world plain.

…

“A lot of personages pass through these pages. The boldface names tend to have a pat of butter, or a droplet of acid, appended to their names: Michael Chabon (‘pretty’), Jane Smiley (‘unaffected and gawky’), Susan Sontag (‘a thumping bore’), Anne Carson (arms ;like pipe cleaners;), Dotson Rader (‘a drunken idiot’), Richard Ford (;probably in the process of killing something with Tom McGuane’), May Swenson (‘helmet-haired’), Shirley Hazzard (‘a studied tweeness’), Lynn Nesbit (‘a truly frightening woman’) and Tom Disch (‘weird polar bear’).

…

“To make it through these diaries, you’ll have to put up with many lines like: ‘Yeah, I get lonely on trips like this, but I’m also a spunky, resourceful little guy. So let’s hear it for Tom tonight!’ You may occasionally fight the urge to pull Tom’s beanie down over his eyes and push his tricycle gently off a pier. On the other hand, it’s hard to dislike the man who wrote, on one Fourth of July in the ’80s: ‘Yes, God Bless America and keep my queer shoulder to the wheel.'”

–Dwight Garner on Thomas Mallon’s The Very Heart of It (The New York Times)

If you buy books linked on our site, Lit Hub may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.