This week’s quintet of quality reviews includes Jia Tolentino on Angela Garbes’ Essential Labor, Justin Torres on Fernanda Melchor’s Paradais, Judith Shulevitz on Tom Perrotta’s Tracy Flick Can’t Win, Forrest Gander on Ada Limón’s The Hurting Kind, and Dwight Garner on Elif Batuman’s Either/Or.

“‘The terrain of mothering is not limited to the people who give birth to children,’ Angela Garbes writes in her new book, Essential Labor: Mothering as Social Change. Raising kids is ‘not a private hobby, not an individual duty,’ she goes on. ‘It is a social responsibility, one that requires robust community support. The pandemic revealed that mothering is some of the only truly essential work humans do’ … Essential Labor is Garbes’s attempt to harness the parental desperation and civic potential of the past two years. It’s partly a history of caregiving in the United States—or, more specifically, a primer on how colonial capitalism and self-regarding feminism made it possible for one of the wealthiest societies in the world to rely, for its basic functioning, on ‘an invaluable force of women, most of them brown and Black, performing our most important work for free or at poverty wages.’ It’s also a call for a guaranteed decent income for domestic workers and caregivers, parents included…Above all, it is an argument that care should be public and universal—that the grace and affirmation that women are asked to bestow on their children should not be limited to mothers, or to parents, or to the private sphere. The book is warm, raw, and occasionally scattered; some sections feel inchoate, animated by a diaristic desire to get longing on the page before it evaporates. Yet, as a lived-in argument for radicalized parenting, Essential Labor is a landmark and a lightning storm, a gift that will be passed hand to hand for years … It was fearsome to consider that the violence undergirding what passes as the American care structure endures because of the thing it can be undone by, which is love.”

–Jia Tolentino on Angela Garbes’ Essential Labor: Mothering as Social Change (The New Yorker)

“‘Better to reign in hell, than serve in Heav’n,’ Satan claims in perhaps the most-quoted line from Paradise Lost. This sentiment serves as driving ambition in the Mexican writer Fernanda Melchor’s disturbing new novel, Paradais, which invokes the epic poem (there’s a character named Milton) but offers no angels, only devils of different variety on either side of the gates … [Melchor’s] translator for both novels, Sophie Hughes, deserves immense credit for capturing the vitality of the prose. But fair warning that this book teems with violence: graphic and aggressive sexual fantasies, anti-gay slurs, incest, murder, torture. If you’re new to Melchor’s work, it might take several pages to adjust. Her sentences contain more clauses than seemingly feasible; single paragraphs run for pages and pages. The visual effect is daunting—an unbroken wall of text—and would perhaps be off-putting if the writing weren’t so seductive. Once you’re acclimated to both the style and the sheer rancor of the prose, you’ll notice other things: flourishes, the attention to the natural world, poetic turns of phrase, shrewd sketches of the indignities of menial labor … Melchor’s Miltonian talent is imbuing ‘evil’ with psychological complexity … the stroke of genius here is cleaving one monster into two.”

–Justin Torres on Fernanda Melchor’s Paradais (The New York Times Book Review)

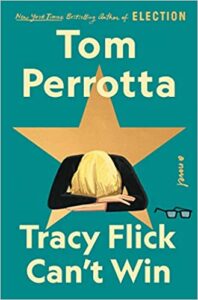

“With Tracy Flick Can’t Win , the sequel to Election the novel, Perrotta joins the ranks of the revisionists. The new book is harsher than the earlier one, reflecting the uglier tenor of our times, as well as, I suspect, Perrotta’s desire to clear up any possible confusion about whose side he’s on. You will not close this book commiserating with the likes of Mr. M. Nor will you wonder whether you missed the nuances. Tracy Flick Can’t Win is frankly didactic. That’s not necessarily a bad thing. Satire has always had an admonitory function, and besides, some people are so obnoxious that a writer has to slow-walk the reader through their awfulness. Plus, Perrotta has what it takes to revisit the past without being predictable … since Election, Perrotta has published seven novels and short-story collections, most of them set in suburbia, thereby acquiring a reputation as a suburban novelist—not another Cheever or Updike, exactly, whose hamlets, however soul-destroying, kept up a veneer of gracious gentility. Perrotta’s are unmistakably in decline … But I don’t think socioeconomic decay is Perrotta’s central concern. What intrigues him is just as pernicious, and not unrelated: American masculinity, or, to be more specific, bro culture … Perrotta’s female protagonists are stymied, but his male protagonists are stunted, often in ways that lead straight to disaster. The best of them realize they’ve got to recover their humanity. Perrotta makes that look pretty hard.”

–Judith Shulevitz on Tom Perrotta’s Tracy Flick Can’t Win (The Atlantic)

“Limón responds in her poetry to what she identifies as an ecological imperative to re-describe our relationship to ‘nature’ in a manner that isn’t merely instrumental. The moving personal dramas that her poems detail can never be separated from the landscape in which they occur … Her poetry, which can feel so intimate and self-revealing, is almost constantly political at the same time … What I might contribute, at the expense of seeming geeky, are some comments on the technical brilliance of Limón’s work, as it is seldom mentioned elsewhere … Most of the lexicon and sentence patterning throughout this poem— and Limón’s other poems— could easily be spoken in conversation. It’s characteristic of Limón’s style that her language reads as both speech and as heightened ‘non-speech.’ It’s a difficult balancing act … Limón isn’t a naive writer; her poetics are informed and slyly in conversation with a historical body of literature … The poems in all four sections of The Hurting Kind cultivate wisdom in domesticity … There are endless things to say about the articulate, complex emotional resonance of the poems in this book. Still, what Limón says about ‘a life’ is true as well for her book: ‘You can’t sum it up.'”

–Forrest Gander on Ada Limón’s The Hurting Kind (The Brooklyn Rail)

“Batuman has a gift for making the universe seem, somehow, like the benevolent and witty literary seminar you wish it were … an even better, more soulful novel. Selin is more confident and, more important, so is Batuman … This novel wins you over in a million micro-observations … When Selin does begin to have sex, she is so perceptive that the scenes are a wonder … Selin wants to be a novelist, but she fears she’s not capable of creating characters other than herself. Across three books, Batuman hasn’t tried to do that. In all three she has written about herself, or something very close to herself, in incremental, almost diaristic form, like an oyster secreting its shell. When you write as well as Batuman does, there are worse fates. But you wonder if the next two novels will recount Selin’s junior and senior years, in a Harvard quartet, and what would happen if Batuman kicked away from shore.”

–Dwight Garner on Elif Batuman’s Either/Or (The New York Times)