Our treasure trove of terrific reviews this week includes J. Courtney Sullivan on Denis Lehane’s Small Mercies, Becca Rothfeld on Brian Dillon’s Affinities, Andrew Motion on Fiona McFarlane’s The Sun Walks Down, John Brandon on Michael Farris Smith’s Salvage This World, and Sam Sacks on Michael Winkler’s Grimmish.

“Excellent and unflinching … The book has all the hallmarks of Lehane at his best: a propulsive plot, a perfectly drawn cast of working-class Boston Irish characters, razor-sharp wit and a pervasive darkness through which occasional glimmers of hope peek out like snowdrops in early spring … There is a tendency on the part of some contemporary authors to exempt their main characters from the prejudices of time and place, to make them more enlightened than they likely would have been. Lehane resists this … One of the more fascinating aspects of the novel is its powerful indictment of the damage done by the Irish mob in Southie, who fomented hate and xenophobia in an effort to keep the community dependent on them and to keep outsiders away … Lehane masterfully conveys how the past shapes the present, lingering even after the players are gone.”

–J. Courtney Sullivan on Denis Lehane’s Small Mercies (The New York Times Book Review)

“Are art critics people, prone to the familiar flurries of aversion and enthrallment? Or are they devices that have been coolly calibrated to assess quality? Conventional wisdom has it that artistic appreciation is ideally an impartial affair, but the Irish critic Brian Dillon protests that he is no bastion of detachment. His lively new collection, Affinities is a compendium of pictures, mostly photographs or stills from films, printed on otherwise blank pages and followed by bouts of commentary. They have been amassed in a single volume not because they are the work of one artist or the products of a single style, but for the simple reason that Dillon is drawn to each of them … If these pictures appear to have little in common beyond Dillon’s predilection for them, their heterogeneity is in part his point. He is intrigued by the obstinate opacity of affinity, which is so misty as to defy definition … Dillon’s forays into what he calls ‘the mundane miracle of looking’ are both impenetrably personal and so rigorously attentive to the external world that the critic sometimes seems to dissolve into the art. He has an affinity, in effect, for affinities—attractions so pronounced that, far from sequestering us in our private passions, they briefly annihilate us.”

–Becca Rothfeld on Brian Dillon’s Affinities: On Art and Fascination (The Washington Post)

“‘White colonial settlers pitched against the outback’ is a familiar trope of Australian fiction, from Henry Lawson and Patrick White to Tim Winton, and in most cases the struggle to survive is treated as a fictional end in itself. Fiona McFarlane’s ambitious novel plays a variation on the theme by paying as much attention to the impact of Denny’s disappearance as it does to the plight of the boy himself … McFarlane’s most significant variation on the theme is to give a large part of proceedings to the Indigenous characters who are drawn into the search … In this respect The Sun Walks Down is a likeable addition to the tradition of which it forms a part: its style is at once spare and attentive to detail, and Fiona McFarlane has a sharp eye for historical injustices. But the ambitious scale inevitably creates problems for the author. The gravitational pull of the novel is generally away from the fact of Denny’s disappearance and towards those who are looking for him, and this produces a sense of structural imbalance, since the further reaches of the narrative are generally more involving than the story that lies at its centre: we never really believe that Denny won’t eventually be found and brought safely home.”

–Andrew Motion on Fiona McFarlane’s The Sun Walks Down (Times Literary Supplement)

“For Southern writers (Smith is from Mississippi), a comparison to Cormac McCarthy can be both an honor and an act of oppression, but McCarthy is an unavoidable point of reference for the bleak elegance of Smith’s prose … The solemn, rhythmic tone is well employed in service of the sodden, gray setting … While Smith’s enthralling narrative talents are plentifully on display in this book, I did find the dialogue a slight letdown. My expectation to receive deeper access to the idiosyncratic personalities of the characters often went unfulfilled, the exchanges too brief or too focused on already-known information. I kept hoping the dialogue would supply avenues for the characters to distinguish themselves from the overarching prickly, reticent demeanor that seems to spring right from the dismal setting and infect everyone in the novel, but it was rarely equal to that task … All in all, Salvage This World is a bruising, bracing read by a hell of a writer. If you consider life too short for uninspired sentences or nondescript locales, this book is for you.”

–John Brandon on Michael Farris Smith’s Salvage This World (The New York Times Book Review)

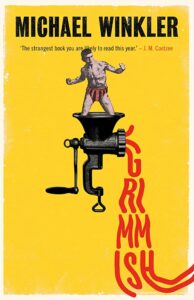

“His book springs from the wondrous and appalling life of Joe Grim (1881-1939), who was born in Italy, began boxing in Philadelphia and made a career from his ability to absorb inhuman beatings in the ring without ever being knocked out. This ‘pain artiste,’ as Mr. Winkler calls him, was more a sideshow than a fighter, a gruesome, cauliflower-eared emblem of our collective fascination with punishment and forbearance … The novel is presented by a nameless alter ego for the author, who visits his elderly Uncle Michael (perhaps another alter ego, Mr. Winkler suggests) and, while plying the old man with sherry, listens to his colorful tales about Grim, particularly those from the boxer’s carnivalesque tour of Australia in 1908-09. Some of what is known of Grim comes from archival research, and Mr. Winkler draws from sensationalized newspaper account of his fights, glorying in the flamboyant verbiage…But as Uncle Michael recalls following Grim through Australia, where factual records are scarce, the accounts become more farcical and bizarre…There’s a quality of Pynchonian buffoonery to these chapters, but because Grim’s life as a human punching bag is absurd on its own, the dividing line between truth and nonsense isn’t always easy to discern … It is somewhat strange to say, then, that the parts of Grimmish that are billed as being the most form-breaking are really the parts that feel the most tired and derivative. Like any genre, today’s experimental fiction has its own conventions and shibboleths: it is fragmentary; it is self-referential; most important, it is autofictional, centering the author within the text.”

–Sam Sacks on Michael Winkler’s Grimmish (The Wall Street Journal)