This week’s five alarm five of fantastic reviews includes Rumaan Alam on Deb Olin Unferth’s Barn 8, Alexander Chee on Paul Lisicky’s Later: My Life at the Edge of the World, Ismail Muhammad on Harry Dodge’s My Meteorite, Robert McCrum on James Shapiro’s Shakespeare in a Divided America, and Paul Franz on Lawrence Joseph’s A Certain Clarity.

“Unferth doesn’t intend to gross us out, but her book doesn’t look away from commercial agriculture’s attempts to adapt nature for the market … it’s when the heist plot kicks in, and we meet a whole parade of well-intentioned kooks, that Barn 8 comes alive. Counterintuitive, maybe, but the caper reveals how serious a book this is … That is not to suggest the novel is a catalog of horrors or a sanctimonious lecture. There’s a joy here, in no small part because of Unferth’s sentences, which are muscular and musical and confident. Beyond Barn 8’s political concerns is an interest in life itself … For those who believe in animal liberation, the question is not political, but moral; my own wavering about the consumption of meat may be unimaginable to them. I was expecting (fine, dreading) a novel that simply gave voice to that conviction, that yelled at a wall. But Unferth is writing in good faith, and she’s also talking about something bigger. She’s a capable guide to the unsettling feeling that governs modern life, a feeling that is very much tied to the billions of animals we eat every year … Humans have just about finished the hard work of destroying ourselves, and we’re seeing more and more art that mourns that fact. This novel does that, with a sly grin. We might be sad about the end of humanity, but the chickens are probably relieved.”

–Rumaan Alam on Deb Olin Unferth’s Barn 8 (The New Republic)

“The chapters are full of named sections, lists of what makes up his life in Provincetown: Haven, Movie, Pilgrim, Foglifter, Wally, Imposter Syndrome. This pointillistic style allows Lisicky to build his story impressionistically. There are no surprises in the general plot, per se: Lisicky becomes the published writer and openly gay man we’ve come to know. But the ‘how’ of it fascinates … He especially captures the fear I’d almost forgotten—the intensity with which we as gay men so often feared one another …This memoir is much like his Provincetown, exulting in tenderness and lust, lit with flashes of poignant spectacle, even the majestic—the way a drag queen at night can become, in sequins under a spotlight, full of the fire and beauty we associate with goddesses, before descending back to the realm of the human.”

–Alexander Chee on Paul Lisicky’s Later: My Life at the Edge of the World (The Los Angeles Times)

“The concept of empathy as an engine for generating solidarity can seem lackluster. As an ideal, empathy requires us to flatten and overlook difference in order to forge bonds, and these days we have to ask ourselves: What kind of love is it that depends on an absence of difference? In his new memoir, My Meteorite, the multidisciplinary artist Harry Dodge, who came to many readers’ attention as the partner with whom Maggie Nelson built a life in The Argonauts, insists that more complex kinds of love are possible … Loosely organized around three narrative strands—the discovery of his birth mother in 2003, the death of his adoptive father in 2017 and his purchase of a meteorite on the internet—the book finds Dodge traversing his life with the aid of a plethora of artistic, pop culture and literary allusions, imagining what it looks like to create ‘solidarity in diversity,’ as he puts it. What would become possible if we thought about love as something whose reach extends to entities that are not like us—perhaps not even human? Dodge’s is a world where a man might have sex with the tailpipe of his car, where the libidinal dimension of an attraction to objects might yield a new understanding of what, exactly, it means to love.”

–Ismail Muhammad on Harry Dodge’s My Meteorite (The New York Times Book Review)

“The readiness is all. Ever since president John Adams rewrote a passage from Henry V to demonstrate how a foreign power might conspire to place a more pliable president in the White House, Shakespeare’s plays have been at the heart of America’s debate about itself … [Shapiro] has plunged fearlessly into the enthralling afterlife of the Complete Works to examine the strange and potent dialogue between Shakespeare’s 400-year-old theatre and the drama of contemporary American politics … describes how all kinds of Americans—assassins, soldiers, hustlers, demagogues and even a few literati—have turned to Shakespeare ‘to give voice to what could not readily or otherwise be said’ … Shapiro’s message, which reverberates through some sparkling chapters on class, immigration and manifest destiny, is that such Shakespeare lines offered a collective catharsis—the story of an assassination refashioned as a national tragedy of Shakespearean dimensions—that allowed the US to defer, once again, its reckoning with the issue that had inspired Booth: the conviction that America, as he put it, ‘was formed for the white not the black man.’ ”

–Robert McCrum on James Shapiro’s Shakespeare in a Divided America (The Guardian)

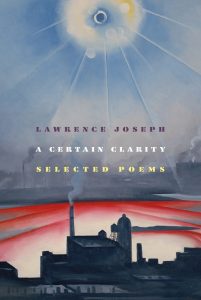

“Joseph self-consciously joins that outsize American tradition of poets-with-professions, poets like Wallace Stevens and William Carlos Williams, from both of whom he has learned much—but, crucially, not too much. From his first collection’s prologue in heaven, in which the not-yet embodied poet is punished for merely amusing his celestial auditors (‘you will be pulled from a womb / into a city’), his founding myth has been of myth disgorging on actuality … Not the first poet to meditate on political economy and empire, Joseph is distinguished by his knowledge, which is not merely technical. Like his 1997 prose study ‘Lawyerland,’ a novelistic portrait of the trade in eight freewheeling, anonymized conversations, his poetry favors blunt words and has an ear for meaty talk … A poetry of force, and of statement, but somehow not always of forceful statement, Joseph’s is one in which verbal extravagance serves a distinctive kind of reverie. Walking or driving, mind and senses keyed up to highest pitch amid his wasted and opulent cities, he lets present and past wash over him.”

–Paul Franz on Lawrence Joseph’s A Certain Clarity (The New York Times Book Review)