Do you know what’s awesome? Scaling 3,000 feet of sheer granite without a harness. Do you know what’s not awesome? Diminishing and objectifying women in the climbing community. Writing in the New York Times, Blair Braverman (an acclaimed author, dogsledder, and adventurer who is as we speak taking part in Alaska’s legendary Iditarod Trail Sled Dog Race) takes issue with Mark Synnott’s depiction of women in his otherwise accomplished account of Alex Honnold, El Capitan, and the climbing life, The Impossible Climb.

From climbing to digging: over at the New Republic, Max Fox enthuses about Hugh Ryan’s When Brooklyn Was Queer, an groundbreaking excavation of the LGBT history of Brooklyn, from the early days of Walt Whitman in the 1850s up through the queer women who worked at the Brooklyn Navy Yard during World War II, and beyond.

Meanwhile, in her considered and illuminating New York Review of Books essay on Valeria Luiselli’s latest hybrid work of fiction and political anger, Lost Children Archive, novelist Claire Messud writes: “Availing herself of a grand American trope—the road novel—Luiselli turns it sideways: her protagonist is no footloose American man, but the immigrant mother of a nuclear family.”

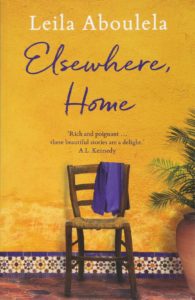

We also take a closer look at The Last Illusion author Porochista Khakpour’s rave New York Times review of Leila Aboulela’s Elsewhere, Home (“the first collection I’ve read since James Joyce’s Dubliners that reminded me of the life-changing power of furiously honest realism”) and Jason Sheehan’s assessment of Salvatore Scibona’s “remarkable” new novel, The Volunteer (“Heavy as it is, there’s a buoyancy to its voices that makes it compulsively readable”).

*

“If literary realism attempts to hold a mirror to the world, then Leila Aboulela’s Elsewhere, Home is an especially vivid reflection in a pond, as accurate as glass’s gaze but rippled to capture life as a thing shivering and fluid even when seemingly still … the force of Aboulela’s writing exceeds its representational significance: She animates so many well-rounded characters who not only honor, but also dare to challenge, the cultures they come from. There are no simple bad-good, European-Muslim dichotomies here. Each individual portrait—and the book operates best as a study in portraiture—is complex, but not gratuitously so … Tales of immigrants are not scarce in the United States, but we Americans nevertheless maintain our shallow concept of their experiences—particularly those of Muslim immigrants in Europe. Khartoum, Cairo, Aberdeen, Edinburgh, Abu Dhabi, London: This book’s diversity of places and perspectives collectively expands, without fanfare, on all the usual tropes of identity … Hers is the first collection I’ve read since James Joyce’s Dubliners that reminded me of the life-changing power of furiously honest realism.”

–Porochista Khakpour on Leila Aboulela’s Elsewhere, Home (The New York Times Book Review)

*

“In his epilogue, he recounts how he also once assumed that Brooklyn had no history of queer community to speak of before the new millennium, when people like he and I (that is, the children of suburbanization) began to move there. But once he began to look for it, he discovered a rich past, from lesbian welders in the Navy Yard to queer culture in bathhouses and freak shows in Coney Island. His larger argument is that ‘the development of Brooklyn would track with the development of modern sexuality’ for roughly a century from 1855 to 1965, when the borough’s postwar industrial decline and urban renewal would also bury these communities. The unique experience of queer communities in Brooklyn during this time, he argues, formed the prehistory to the modern gay liberation movement and its signal event, the Stonewall riots. It’s a satisfying retort to the idea that there was nothing queer there before … The archival discoveries that Ryan has made evoke a world of affection and pleasure that is at odds with the prevailing story that sexual liberation only began in the 1960s and followed centuries of unremitting suffering and oblivion … Ryan’s history posits that the urban world of prewar Brooklyn produced a certain kind of queer, and that postwar suburbia enforced a kind of forgetting. The prodigal return of the suburban queer to the city is often underwritten by the promise of redeeming a sense of unclaimed belonging, and Ryan’s archaeology successfully seems to notarize it.”

–Max Fox on Hugh Ryan’s When Brooklyn Was Queer (The New Republic)

*

“For all their inventiveness, neither of her earlier novels could have led readers fully to anticipate this ambitious, somber, urgent new work … Luiselli plays with reality and literary convention (in a manner familiar from European and Latin American fictions from Pirandello to Borges to Bolaño) and combines that play with an often ironic, intermittently autofictional recording of daily life’s more banal moments, in a way popularized in contemporary North American fiction by women writers like Sheila Heti or Jenny Offill … As the family travels westward the parents’ relationship deteriorates, while the plight of the immigrant children at the border grows increasingly pressing. Availing herself of a grand American trope—the road novel—Luiselli turns it sideways: her protagonist is no footloose American man, but the immigrant mother of a nuclear family. They travel not between coasts but away from the city, from the center to the margins—their progress, if it can be called that, recalls The Sheltering Sky more than On the Road … games and allusions are important to the texture of Lost Children Archive. Luiselli’s stylistic freedoms—roaming from the adult narrator’s highly realistic (and, one suspects, often autobiographical) reflections to the child’s frankly implausible fairy tale adventure, to the dark myth-like storytelling of the Elegies—form a patchwork designed simultaneously to reflect and reinterpret our current reality … Many elements of Lost Children Archive are extraordinary, and yet the ultimate act of transformation has not occurred. One might of course contend that, in this ghastly time, such a transformation is no longer possible; but Luiselli’s decision to write a novel at all surely affirms otherwise.”

–Claire Messud on Valeria Luiselli’s Lost Children Archive (The New York Review of Books)

*

“It is a war story unlike any other war story, a story of fathers and sons, of family (both biological and manufactured) and of generations of betrayal and abandonment. It takes a single thesis, argued a billion times before—that some sins are hereditary, passed down from men to their sons who are doomed to repeat them—and argues it across hundreds of pages. Sound dull? You’re wrong. Tired and worn-out? Not even a little. Not here, in Scibona’s hands, where the simplest things (nature, pride, a white t-shirt, the taste of water from one’s home place) become mythic and strange, almost magical, imbued with meanings beyond the plain fact of their existence … The Volunteer actually walks the edge of magical realism. Not deliberately, I don’t think; not through any design of the plot or minds of its characters (because these are pragmatists Scibona offers us, each of them pared down to the bone by tragedy and seemingly inescapable destiny). But the way Scibona writes, there are few moments that don’t feel enlivened with something…more. Something extra. Some secret power of history, family or fate thrumming away unseen behind the curtains of the world, driving events … Scibona is a remarkable writer and The Volunteer is a remarkable book … Heavy as it is, there’s a buoyancy to its voices that makes it compulsively readable, a dogged survival instinct that makes even its darkest moments bearable. The characters get under your skin. They climb into your head and live there long after you close the covers, and you will take their joys and miseries to bed with you for a long time after.”

–Jason Sheehan on Salvatore Scibona’s The Volunteer (NPR)

*

“The Impossible Climb is an accomplished portrait of two remarkable lives—but its major weakness, of both style and imagination, lies in Synnott’s depictions of women. Professional climbing is largely a man’s world, but rather than examine this dynamic as he does countless others, Synnott uses descriptions that further diminish and objectify the women he encounters. Consider one whom the men meet in Borneo: She has a name, but we don’t know it, because the men dub her Hello Kitty. What do we learn about Hello Kitty? She’s petite, she has big breasts and—in a moment that clearly looms large in Synnott’s memory—she goes braless at breakfast one morning. Other women are ‘feisty,’ ‘effervescent,’ ‘sexy,’ ‘voluptuous’ or have a ‘smile that would make most men melt.’ The top-ranked climber Emily Harrington is ‘spunky and quite attractive.’ These lazy descriptions are startling given Synnott’s nuanced treatment of even incidental male characters, but the contrast is no coincidence. Like a jazz record or a dog-eared book by Dostoyevsky, the women here are simply another tool for characterizing the men around them—as well as vehicles for Synnott’s fascination with the younger Honnold’s sex life. This fascination is shameless and enduring, fitting into themes of aging that build throughout the book. Aging is, after all, what happens if you don’t die, and after decades of risk-taking, Synnott is finally forced to grapple with the consequences of survival.”

–Blair Braverman on Mark Synnott’s The Impossible Climb: Alex Honnold, El Capitan, and the Climbing Life (The New York Times Book Review)