Our feast of fabulous reviews this week includes Amal El-Mohtar on Kelly Link’s The Book of Love, Megan Milks on Lucy Sante’s I Heard Her Call My Name, Isabella Trimboli on Helen Garner’s The Children’s Bach, Alexandra Jacobs on Diane Oliver’s Neighbors and Other Stories, and Claire Dederer on Sheila Heti’s Alphabetical Diaries.

“Seven years in the making, The Book of Love—long, but never boring—enacts a transformation of a different kind: It is our world that must expand to accommodate it, we who must evolve our understanding of what a fantasy novel can be. Reviewing The Book of Love feels like trying to describe a dream. It’s profoundly beautiful, provokes intense emotion, offers up what feel like rooted, incontrovertible truths—but as soon as one tries to repeat them, all that’s left are shapes and textures, the faint outlines of shifting terrain … It’s common to read a book with a strong sense of place and say that the setting is a character in the story. But in The Book of Love, it’s more correct to say that characters provide the story’s setting: Each ‘Book’ is a dwelling place to experience a life, and taken together, the result is immense. As C.S. Lewis wrote of heaven and John Crowley wrote of fairyland, the further in you go, the bigger it gets—an experience that recalls the process of getting to know a person … The Book of Love does justice to its name. Its composition, its copiousness, suggests that love, in the end, contains all—that frustration, rage, vulnerability, loss and grief are love’s constituent parts, bound by and into it.”

–Amal El-Mohtar on Kelly Link’s The Book of Love (The New York Times Book Review)

“Over the past decade or so, trans memoir has tended to fall into two categories. There’s the straightforward version penned by a newly out public figure—directed to a mainstream audience and organized around transition as a main event (or series of events). Then there’s the more self-consciously stylized work of personal nonfiction by a non-famous writer who is trans—who might engage with the form of the transition narrative but do so with a wink, a shrug, or a metaphorical or conceptual conceit (running, weather, jokes). This second category is in a vexed and critical relationship with the first, which does not give back, unaware that its enemy exists. Lucy Sante’s new book, I Heard Her Call My Name, tilts toward the first (no surprise: see the subtitle), but in some ways bridges both categories … This is not the first record that Sante has shared of her life, and hardly the only one. What makes I Heard Her so compelling is how Sante uses this new trans lens to retell a life already told … Coming out in her sixties has entailed a painful confrontation with this former self but is an ‘enormous relief.’ I Heard Her is a sustained and joyful exhale … Sante writes from this space of serenity. The warm, companionate narrator Sante has let loose is the book’s most moving achievement. It’s a beautiful clarity of self to be invited into, and Sante’s is a remarkable life to see anew, through this rush of intimacy and wonder.”

–Megan Milks on Lucy Sante’s I Heard Her Call My Name (4Columns)

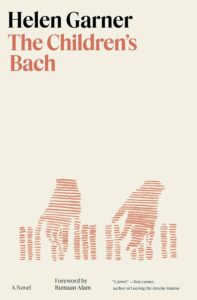

“Seclusion rarely registers in Garner’s books: She is invested in the muck of collective life, with all of its brutalities, ironies, and ambivalences. In her fiction, these relations play out in the home, a place elastic and unstable, where people are constantly being brought in or shoved out. A couple is never just a couple; there are kids and sisters and friends and former partners to look after. Even when she stopped writing about the interchangeable intimacies of the sharehouse, Garner examined relationships and obligations in flux, the strange new clusters that could form under such mercurial circumstances. It’s as if the sticky fingerprints of the era’s unrealized promises of freedom, sex, and reconfigured families could never fully be scrubbed off. They are all over The Children’s Bach, Garner’s second and best novel, in which the sedate joys and monotonous order of family life are shaken and, eventually, fall to pieces. With its slippery form and flickering perspectives, the novel offers its own kind of disturbance to the conventions of the domestic drama. The Children’s Bach inverts Goethe’s famous description of chamber music as ‘rational people conversing’: In Garner’s hands, it becomes a clamor of voices, images, and instruments that prove to be unreliable and full of doubt. Love and understanding are fought for anyway.”

–Isabella Trimboli on Helen Garner’s The Children’s Bach (The Nation)

“At a moment when short stories seem less regular launchpads for long careers than occasional meteors, reading these is like finding hunks of gold bullion buried in your backyard. Oliver’s primary topic—she didn’t have enough time on this earth to develop many—was the private bulwark of the family, during a time when Jim Crow ‘separate but equal’ laws still ruled the South … Such luminous simplicity is deceptive; these stories detail basic routines of getting through difficult days, but then often deliver a massive wallop. That might just be a variant on the phrase ‘you people,’ the cold shock of casual, legitimized racism spoken out loud or as internal monologue … Neighbors and Other Stories is not wholly polished; how could it be? The experimental ‘Frozen Voices’ whorls around and around confusingly, repetitively—something about an affair? A plane crash? ‘I never said goodbye,’ the narrator intones again and again. Jet magazine was one of the few periodicals to say goodbye to Diane Oliver with an obituary. Thanks to this collection, The New York Times now belatedly bids a full-throated hello.”

–Alexandra Jacobs on Diane Oliver’s Neighbors and Other Stories (The New York Times)

“I read it over the holiday season, when lots of people were coming and going from the house, and everyone seemed to want to know more about it. Their curiosity turned quickly to skepticism—the historically correct response to the avant garde. So, to answer the question: Yes. Absolutely. The book is boring. Sometimes. It’s also thrilling, very funny, often filthy, and a surprisingly powerful weapon against loneliness, at least for this reader. How it achieves all this has to do with the sentences themselves, but even more than that with the unlikelihood of their arrangement; it’s the sentences’ crackpot proximity to one another that makes them sing (admittedly a very odd song) … Heti’s structure allows her to represent the mind wandering; but also the way it loops and doubles back on itself, reworking over and over the same problems (intractable writing projects, envy of a successful friend, a stubborn attraction to difficult and dominating men). None of this appears wildly novel on its face: the representation of consciousness is hardly a newfangled concern for a book, and Heti’s commitment to the alphabet recalls the work of other experimentalists in narrative restriction, such as Georges Perec, whose novel La Disparition doesn’t contain a single letter ‘e.’ Even so, Alphabetical Diaries ends up, I think, in truly surprising territory. Heti has outsourced authorship to the alphabet; it is in charge of arranging the material; it supersedes time itself. In this way, Heti disrupts the tidying up of identity that memoirists unconsciously perform.”

–Claire Dederer on Sheila Heti’s Alphabetical Diaries (The Guardian)