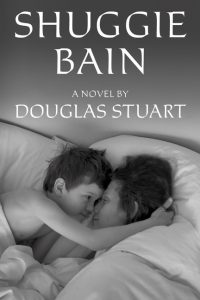

This week’s quintet of quality reviews includes Leah Hager Cohen on Douglas Stuart’s Shuggie Bain, Leslie Jamison on Jenny Offill’s Weather, James Wood on Daniel Kehlmann’s Tyll, Gabino Iglesias on Tola Rotimi Abraham’s Black Sunday, and Sam Sacks on Andrew Krivak’s The Bear.

“The body—especially the body in pain—blazes on the pages of Shuggie Bain…The most common form of suffering in this novel is that which characters inflict on themselves: poisoning themselves with drink, putting their heads in the oven, setting the bedroom on fire, egging on aggressors, rebuffing love, refusing help … This is the world of Shuggie Bain, a little boy growing up in Glasgow in the 1980s. And this is the world of Agnes Bain, his glamorous, calamitous mother, drinking herself ever so slowly to death. The wonder is how crazily, improbably alive it all is … Douglas Stuart writes in a sense-drenched Glaswegian prose so studded with slang and phonetically rendered dialogue that the language itself adds up to another layer of physicality, a rhythmic reel coursing through the reader’s blood … The book would be just about unbearable were it not for the author’s astonishing capacity for love. He’s lovely, Douglas Stuart, fierce and loving and lovely. He shows us lots of monstrous behavior, but not a single monster—only damage. If he has a sharp eye for brokenness, he is even keener on the inextinguishable flicker of love that remains … The book leaves us gutted and marveling: Life may be short, but it takes forever.”

–Leah Hager Cohen on Douglas Stuart’s Shuggie Bain (The New York Times Book Review)

“Preoccupied by the apocalyptic horizon of climate change, the dark pulsing terror at the center of the novel, and by the ‘feeling of daily life,’ Lizzie understands—or at least, enacts—the truth that we inhabit multiple scales of experience at the same time: from the minutiae of school drop-offs and P.T.A. activism to the frictions of our personal relationships all the way to the geological immensity of our (not so slowly) corroding planet. Offill takes subjects that could easily become pedantic—the tensions between self-involvement and social engagement—and makes them thrilling and hilarious and terrifying and alive by letting her characters live on these multiple scales at once, as we all do … Offill’s writing is shrewd on the question of whether intense psychic suffering heightens your awareness of the pain of others, or makes you blind to it … part of the brilliance of Offill’s fiction is how it pushes back against this self-deception … If I responded more strongly to Dept. of Speculation than to Weather, it might be a testament to the narrative dilemma the new novel is reckoning with: the scale of its ambition, despite its brevity, in its attempt to tell a story about climate change that carries the same visceral force as our private emotional dramas—that is, in fact, inseparable from them … Offill’s whittled narrative bursts are apt vessels for the daily experience of scale-shifting they document—the vertigo of moving between the claustrophobia of domestic discontent and the impossibly vast horizon of global catastrophe … Offill’s fragmentary structure evokes an unbearable emotional intensity: something at the core of the story that cannot be narrated directly, by straight chronology, because to do so would be like looking at the sun.”

–Leslie Jamison on Jenny Offill’s Weather (The New York Times Book Review)

“Kehlmann, a confident magician himself, plays his bright pages like cards. But he has a deeper purpose, which is revealed only gradually, as the grand climacteric of his chosen war steadily justifies its presence in the novel … A remote historical period, rollicking picaresque episodes, tricksters and magic, ancient foggy chronicles—all the dangers of the historical novel are here … Kehlmann is a gifted and sensitive storyteller, who understands that stories originate within communities, and that such stories are convincingly dramatized when the novelist selflessly inhabits his characters’ perspectives … The book’s narrative is daringly discontinuous … Despite the grimness of the surroundings and the lancing interventions of history, the novel’s tone remains light, sprightly, enterprising. Kehlmann has an unusual combination of talents and ambitions—he is a playful realist, a rationalist drawn to magical games and tricky performances, a modern who likes to look backward … is vivified by the remoteness of its setting and the mythical obscurity of its protagonist, which oblige Kehlmann to commit his formidable imaginative resources to wholesale invention, and to surrender himself to the curious world he both inhabits and makes. At once magister and magician, he practices the kind of novelistic modesty that can be found at the heart of classic storytelling.”

–James Wood on Daniel Kehlmann’s Tyll (The New Yorker)

“Tola Rotimi Abraham’s Black Sunday will destroy you. It won’t be an explosion or any other ultraviolent thing. Instead, the novel will inflict a thousand tiny cuts on you, and your soul will slowly pour from them … The first standout element in Black Sunday is the writing itself. Abraham mixes poetry, Yoruba, pidgin English, and street philosophy into a mesmerizing style. The novel’s chapters alternate between the point of view the four siblings, and each one has a distinctive voice that makes whatever they’re talking about feel like something that happened to someone you know … Once all the money is gone, the narrative takes a turn and every subsequent page is like a punch to the gut…Luckily, Abraham knows readers can only put up with so much, so she relents on the violence from time to time, gifting us brilliant moments of love and humor whose impact is amplified by the awfulness that surrounds them. Black Sunday is a literary wound that bleeds pain for a while, but you should stay the course, because that’s followed by lots of love, beauty, and hope.”

–Gabino Iglesias on Tola Rotimi Abraham’s Black Sunday (NPR)

“Humankind pleases Andrew Krivak so little that he has killed off almost all of it for his strange and strangely tender apocalyptic fable The Bear. Set a few generations after an unspecified extinction event, the novel follows the last two humans on Earth, a father and daughter who live in what appears to be the mountains of New Hampshire. Like Cormac McCarthy’s The Road, the novel is centrally about the parent-child bond and the teachings that go into survival. Yet Mr. Krivak’s novel shares none of that book’s sense of doom or horror. The Bear is interested in continuity, the ways that life will persevere and age-old knowledge will still be transmitted after the end of man’s dominion … Mr. Krivak balances this sort of mysticism with closely observed descriptions of sewing leather for shoes, carving wood for bows and arrows or spotting eddies to fish for trout. These activities are endowed with such fullness of meaning that you have to assign this short, touching book its own category: the post-apocalypse utopia.”

–Sam Sacks on Andrew Krivak’s The Bear (The Wall Street Journal)