Our barrel of brilliant reviews this week includes Alexandra Kleeman on Danzy Senna’s Colored Television, Jennifer Wilson on Ann Schmiesing’s The Brothers Grimm, Hugh Ryan on Mikaella Clements & Onjuli Datta’s Feast While You Can, Jack Hamilton on Alex Van Halen’s Brothers, and Alexandra Jacobs on Bill Zehme with Mike Thomas’ Carson the Magnificent.

“What follows is a plot common to many movies and books about writers who’ve ventured into Hollywood lured by the promise of easy winnings: endless meetings and notes on the promise of success to come, and then, finally, a twisty bit of intellectual property theft that crushes Jane’s dreams while simultaneously offering crucial affirmation of her instinct for story.

Senna’s protagonists are often driven by the longing to choose a side: the plots that ensnare them are generated by the difficulties of making it, securely, from one side to the other … Jane, too, wants to choose a side—but after securing the photogenic dream family she once saw in a Hanna Andersson catalogue (rugged Black husband, two cute brown kids), her truest longing is for an upper-class LA lifestyle far from financial precarity, the kind of life those around her seem to be living regardless of their race. But no matter how much Jane wishes to identify as bourgeois, class is one type of identity that cares little for how you identify or declare yourself: your net worth has the final say.

With this sly sleight of hand, Senna deftly scrambles hierarchies of race, class, and culture, leading Jane through an absurdist take on the culture machine, where the dynamics of industry approval are as labyrinthine as the cultural construction of race. Hampton privately bemoans the dilution of Black experience as his inexplicably white-presenting daughter mingles with the mixed children of Kardashians at a birthday party, but he nevertheless works to create content for biracial viewers because it is, in his words, ‘the fastest-growing demographic in the country.’ Jane’s highbrow novel about niche multigenerational experience does not have sufficient mass appeal to interest the publishing industry, and her more commercial pitch for a quasi-utopian family comedy where all conflict is comedic is not sufficiently highbrow for a creator of lowbrow content who hopes to make it firmly into the middlebrow—nor is it in his words ‘sufficiently biracial.’ ‘I can make it more biracial,’ Jane offers in desperation, as Hampton shoots down yet another episode premise. This is a culturally extractive industry, and Jane is expected to help the system mine her demographic, fracking the self for little bits of essential experience that can be processed into a general cultural narrative.”

–Alexandra Kleeman on Danzy Senna’s Colored Television (Bookforum)

“Though posterity has conjoined them, Jacob and Wilhelm were two rather disparate men. Wilhelm was the bon vivant to Jacob’s introvert. The elder was the more accomplished scholar … And yet a joint biography is the only kind that feels appropriate; posthumously disentangling one brother from the other seems tantamount to desecrating a corpse, for Jacob and Wilhelm were ardently inseparable. When, during their undergraduate years, Jacob briefly worked abroad for one of their professors, Wilhelm wrote to him, ‘When you left, I thought my heart would tear in two. I couldn’t stand it. You certainly don’t know how much I love you.’ Jacob pledged that it would never happen again, and sketched out what he hoped their life would look like after they completed their studies: ‘We will presumably at last live quite withdrawn and isolated, for we will not have many friends, and I do not enjoy acquaintances. We shall want to work with each other quite collaboratively and to cut off all other affairs.’ When Wilhelm married, Jacob lived with his brother and new sister-in-law. A friend once addressed the brothers in a letter as ‘My dear double hooks!’

…

“Schmiesing’s biography of the Grimms is the first major English-language one in decades. It can be dense with details, but when I read Murray B. Peppard’s Paths Through the Forest (1971), a more approachable biography of the Grimms, I found myself missing Schmiesing’s unrulier thickets of Prussian bureaucrats and long asides about German grammar. Hers is hearty German fare. It also presents findings that complicate the brothers’ image as ethnographic purists.

…

The Grimms’ stories, with their promise of bodying forth an authentically Teutonic spirit, were so sought after during the Nazi years that Allied occupying forces temporarily banned them after the war. Scholars have since stressed that their nationalism was rooted in a shared cultural and linguistic heritage, not blood and soil. Still, the task of narrating the lives of Jacob and Wilhelm remains as thorny as the hedge that trapped Briar Rose’s suitors. As Schmiesing writes, it ‘entails navigating between too naively or too judgmentally presenting the nineteenth-century constructions of Germany and Germanness to which they contributed.’

In truth, this ambivalence existed for Jacob, too, who worried that the standardization of German in schools might downgrade dialects and the very folk speech that their lives had been devoted to capturing. The brothers knew better than anyone that every story of enchantment is also a story of disenchantment, and their lifelong cause was no exception. The nation has proved to be humanity’s most cherished fairy tale, and its grimmest.”

–Jennifer Wilson on Ann Schmiesing’s The Brothers Grimm: A Biography (The New Yorker)

“For queer women, horror and hunger have stuck cheek by jowl since at least the time of Carmilla, the ur-Sapphic vampire novel from 1872. The figure of the devouring lesbian is both a symbolic inversion of the good, sacrificing mother and a tantalizing embodiment of the male terror of cunnilingus. But this familiar paradigm is queerly inverted in Feast While You Can, Mikaella Clements and Onjuli Datta’s exciting new hybrid horror-romance novel. Angelina and Jagvi, the novel’s monster-crossed lovers, race to escape an ancient entity that wants to devour more than just their bodies.

…

Like many creative works set in the queer ’90s, the book doesn’t grapple with the pervasiveness of the period’s xenophobia. Although the monster as metaphor for homophobia is strong, the representation of actual homophobia and racism is rather weak: noted on a surface level, but for the most part, vaporous and indistinct. Perhaps Clements and Datta rightly intuit that more explicit references would swamp the lighter, more adventurous, exciting, fantastical and erotic parts of the novel. But readers familiar with the era may feel ungrounded.

Where the novel sings, however, is in its representations of queer life and desire … Queer women have always been part of the horror genre. But in the capable, beckoning hands of Clements and Datta, we get to see the story from their perspective, with monsters made not from them, but for them. In Feast While You Can, queer desire is the cure, not the curse, and it will satiate readers who have subsisted for too long on the crumbs of representation.”

–Hugh Ryan on Mikaella Clements & Onjuli Datta’s Feast While You Can (The New York Times Book Review)

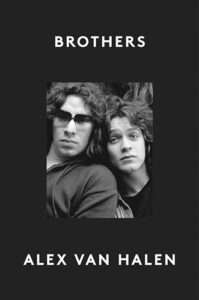

“Alex Van Halen’s new memoir, Brothers, is the elder Van Halen’s first extended public statement since his brother’s death, and his grief is present on every page … But Brothers is anything but a downer — co-written with the New Yorker’s Ariel Levy, it’s a funny and breezily charming read, one of the sweetest and most introspective rock memoirs in recent memory. As the book’s title suggests, it’s not so much Alex’s own story as the story of his relationship with his younger brother. It also doesn’t attempt to encompass the full scope of their life together, choosing to conclude at the band’s critical and commercial zenith, their 1984 masterpiece 1984. (Van Halen had a way with album titles.)

…

It’s this period of the band’s career that Alex writes about most wistfully and most affectingly—much like John Lennon’s famous remark that the Beatles’ best work was never recorded, the drummer maintains a nostalgic attachment to the scrappy purity of those early years. ‘That’s when the dream of Van Halen was most magical—because it was still a dream,’ he writes. ‘There’s nothing more exciting than thinking you’re on the verge of achieving everything you’ve ever wanted. Including achieving it.’

Alex is fond of a good quote—Oscar Wilde, Friedrich Nietzsche, Michelangelo and Paul McCartney are just a few luminaries whose aphorisms (real or apocryphal) appear in these pages. But his most frequent interlocutor is his late brother, whose words Alex produces with striking regularity throughout the book. At points Brothers almost feels like a posthumous conversation between the two, the implications of which are as touching as they are sad, Alex poring over interviews that Ed gave through the many decades of their band’s stardom, straining to hear his voice one more time.”

–Jack Hamilton on Alex Van Halen’s Brothers (The Washington Post)

“Maybe late-night TV shouldn’t be called ‘late-night TV’ anymore, with so many viewers consuming it in clips the morning after, on their phones. Yet the genre’s hallmarks—the avuncular host, the sidekick, the band, the monologue, the desk, the guests—linger. Most were stamped on America’s consciousness by Johnny Carson.

A new biography about an old reliable, Bill Zehme’s Carson the Magnificent harks back to an era when doom and scroll were biblical nouns and Carson’s Tonight Show was a clear punctuation mark to every 24-hour chunk of the workweek—less an exclamation point, maybe, than a drawn-out ellipsis. ‘They want to lie back and be amused and laugh and have a nice, pleasant and slightly … I hate the word risqué … let’s say adult end to the day,’ is how a producer in 1971 described the millions tuning in from home, to Esquire.

…

Short but florid, Carson the Magnificent is a memorial of the monoculture; a steady parade of mostly men chatting companionably to one another on a padded sectional.

…

There’s a kind of mirroring going on here. Carson’s work was to keep the show going, not to dwell on unpleasant topics (including politics), and Zehme follows suit. He runs through the curriculum vitae with a brisk ring-a-ding … On air, Carson would take on various goofy guises, including the turbaned Carnac the Magnificent. The book’s title, and its light glide over his womanizing and sometimes violent alcoholism, suggest that in real life, too, he was a master of disguise and escape.”

–Alexandra Jacobs on Bill Zehme with Mike Thomas’ Carson the Magnificent (The New York Times)