Our quintet of quality reviews this week includes Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie on Barak Obama’s A Promised Land, Michael Wolff on Evan Osnos’ Joe Biden, Jo Livingstone on Chelsea G. Summers’ A Certain Hunger, Brian Dillon on Marjorie Garber’s Character, and Michael Gorra on Don DeLillo’s The Silence.

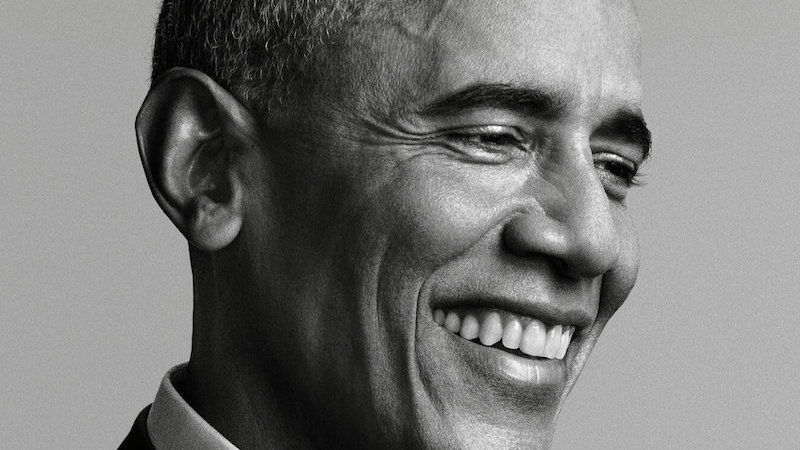

“Barack Obama is as fine a writer as they come. It is not merely that this book avoids being ponderous, as might be expected, even forgiven, of a hefty memoir, but that it is nearly always pleasurable to read, sentence by sentence, the prose gorgeous in places, the detail granular and vivid … His focus is more political than personal, but when he does write about his family it is with a beauty close to nostalgia … There is a romanticism, a current of almost-melancholy in his literary vision … Obama’s thoughtfulness is obvious to anyone who has observed his political career, but in this book he lays himself open to self-questioning. And what savage self-questioning … It is fair to say this: not for Barack Obama the unexamined life. But how much of this is a defensive crouch, a bid to put himself down before others can? … And yet for all his ruthless self-assessment, there is very little of what the best memoirs bring: true self-revelation. So much is still at a polished remove. It is as if, because he is leery of exaggerated emotion, emotion itself is tamped down … And then there are his biographical sketches, masterful in their brevity and insight and humor … But it is on the subject of race that I wish he had more to say now. He writes about race as though overly aware that it will be read by a person keen to take offense … He is a man watching himself watch himself, curiously puritanical in his skepticism, turning to see every angle and possibly dissatisfied with all, and genetically incapable of being an ideologue … The story will continue in the second volume, but Barack Obama has already illuminated a pivotal moment in American history, and how America changed while also remaining unchanged.”

–Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie on Barack Obama’s A Promised Land (The New York Times)

“… it’s refreshing—even cleansing—to be here again, to read an admiring biography about a normal politician. Of course it is dull too … Here we see the journalist in sync with the aspirations and craft of the politician, admiring, often in awe of, his subject’s driving ambition to rise in the political structure, and his skills in accomplishing this. There isn’t, traditionally, much of an ideological basis to such political portraiture. All winners are due their attentive books, and such special-access tracts (Osnos is granted quite a bit of one-on-one time with Biden the candidate) tend to be produced by those who have shown their relative deference. Only the most gullible reader might miss the clear partnership between the politician and political writer in a traditional campaign biography … Osnos is an old-fashioned political writer … Osnos the younger is not setting out to look for deficiencies or expose scandal but to set out virtues. And not, mind you, ideological virtues but political ones: his subject’s astuteness, acumen and fortune as a politician … Osnos’s lacklustre prose suggests he didn’t know he had such a big story, even as Biden began to prosper in the primaries, and in fact there is a sense of the author feeling somewhat lumbered with the Biden beat. His subject emerges as a worthy but default figure, the best all-purpose, anybody-but-Trump candidate.”

–Michael Wolff on Evan Osnos’ Joe Biden: The Life, the Run, and What Matters Now (The Times Literary Supplement)

“A Certain Hunger is not a horror novel or a thriller but more like a symbolic comedy determined to make the whole ‘ironic misandry’ schtick into something complicated and engaging. Though both rape and revenge feature in the story, it is not a rape-revenge plot. The precision and passion Dorothy bring to murder have a stronger relation to her obsession with food … as a narrator, Dorothy does have more in common with murderer-narrators like Patrick Bateman, Tom Ripley, or Jean-Baptist Grenouille from Patrick Süskind’s influential novel Perfume…in both books the collective weight of sensory images slowly creates something like an ethic of murder, posing violence as a creative act with an inevitable relationship to other forms of art—murder as a tribute to beauty … It’s difficult to joke about killing men or burning books in writing these days, because humorless people on the internet are so eager to take you seriously: I’m sure a handful of readers will find A Certain Hunger insulting to their masculinity, or misread it as a Satanic call to feminists everywhere to spatchcock their husbands. But most readers will find Summers to be a writer in charge of compelling new powers, and the sheer absence of guilt or remorse in Dorothy a refreshing antidote to the anxious moral calculus so popular in much contemporary fiction. A Certain Hunger is a swaggering, audacious debut, and a celebration of all the wet, hot pleasures of human contact.”

–Jo Livingstone on Chelsea G. Summers’ A Certain Hunger (The New Republic)

“Character names at once an ideal or aspiration and an ineradicable mark; a state to be arrived at by will; and a condition requiring education, leadership, and propitious circumstance. ‘Is character innate, learned, taught, or instilled? Are character traits fixed or changeable? Do they depend on heredity, on environment, on parents, teachers, mentors, or life experiences?’ Garber asks versions of these questions throughout, but she considers them chiefly literary—that is, ‘questions about the way something means, rather than what it means,’ … The strength of Garber’s book therefore lies less in adducing a present value for the concept than in her wide-ranging account of how we arrived at the confused and confusing things it has meant and means now … Her account of character as a literary and cultural category, and how it has literally or figuratively been read in real or imaginary individuals, may well be the book’s strongest aspect. The modern understanding of character, she argues, is not just adjacent to, but actually derived from, fictional characters: their construction on the page, but also their concerns about the character of their peers … The richness of this history is what makes Garber’s book fascinating, and also, perhaps, the reason she does not want to relinquish the idea at the last, and instead hopes that there is intellectual and ethical life in a word that has outlived its history.”

–Brian Dillon on Marjorie Garber’s Character: A Cultural Obsession (Harper’s)

“The Silence is full of voices, a work of talky minimalism whose characters are all troubled by the absence of sound…this is Don DeLillo, for whom white noise is both comfort and scourge. It deadens our senses even as it allows us to endure what they tell us, and for him that silence is a roar … DeLillo has an eye for iconic moments of American violence: the first Kennedy assassination in Libra (1988), the September 11 attacks in Falling Man (2007). It’s no surprise to find him drawn to the saturnalia of Super Bowl Sunday, and indeed he’s written about football before, in his early End Zone (1972), which presented that militarized sport as though it were nuclear war. Or maybe it’s the other way around, as though each of them meant the other. For events in DeLillo’s world are often inseparable from the figures of speech that define them, reality indistinguishable from its simulation. Meaning softens and blurs, and his people are more apt to enjoy that phenomenon than to worry about it … His fascination with a numinous world that may not mean anything at all: that’s his equivalent of Balzac’s greedy-eyed fascination with money. He loathes it and loves it, but nobody else sees American life as he does, and so I now factor in his flaws and focus on what remains … DeLillo likes death, the mother of beauty. He likes it as a subject, a shaping force: the one thing that can make his world’s gleaming thrills seem shallow. It is always out there waiting … We live longer now, and though their work may slow and fade, few artists ever announce their retirement. Roth famously did, and Alice Munro. Those are the exceptions. Still, I think that most people who read The Silence will ask how one might come to an ending; will recognize that both the inevitability and the impossibility of ending provide this slender tale’s real subject … Edward Said writes that in late style death appears refracted as irony; Adorno that such works are the catastrophes of art. Some pages in this book verge on self-parody, and I doubt it will draw any readers who haven’t already invested themselves in DeLillo’s work, in the half-century of risks his voice has taken. But those of us who have will find something poignant and terrible in this strange unbroken silence.”

–Michael Gorra on Don DeLillo’s The Silence (The New York Review of Books)