Our feast of fabulous reviews this week includes Erin Somers on Taffy Brodesser-Ackner’s Long Island Compromise, Christian Lorentzen on Tony Tulathimutte’s Rejection, Daniel Felsenthal on Gary Indiana’s Horse Crazy, Ryan Ruby on Rachel Kushner’s Creation Lake, and Mary Turfah on Ang Swee Chai’s From Beirut to Jerusalem.

“These events could constitute a novel in their own right. But this is just the opening episode of a long, multi-voice family drama about suburban New York life and the secrets it holds. One might expect a lot more action to come—further stories of conspiracy and crime and hardship—but though the opening has the makings of a movie as much as a novel, the rest of Long Island Compromise tends to direct its attention to the lingering effects of this initial event. Questions of wealth and class, Jewish identity, and family tensions are compellingly set up at the beginning but then fall away, or become muddled, by the end. Instead, we get a novel that leans heavily on backstory, in which flashbacks establish characters and single traumatic moments—even those that happened well before the characters were born—end up determining who they are.

…

Brodesser-Akner is interested in the rarefied worlds of the upper classes—the Manhattan private-school set in Fleishman, the gated estates of suburbia in Long Island Compromise. These books aspire to the comedic, yet though they have their moments of crisp social observation and witheringly accurate detail, they are not quite satire. Any criticism of the way the rich live is defanged by the same explanation over and over: These rich people live this way because someone hurt them.

If Fleishman Is in Trouble is the epitome of the ‘What happened to her?’ novel, a book about the pain that women suffer under patriarchy, then Long Island Compromise could be fairly called a ‘What happened to them?’ novel, a book about the foundational trauma that forever shapes a family’s dynamic. Just as [Parul] Sehgal warned, even the splashiest elements of the plot begin to feel oddly inconsequential in the face of such trauma. The tension of the novel dissipates; the impression increasingly becomes that everything that matters to these characters has already happened. So what compels the reader to continue?

…

…the insights about the Jewish experience and what a Jew can be feel tacked on and belated, and it is hard for the reader to connect the bad behavior of the Fletcher children with the Holocaust. The book is not a study of Jewish trauma, as it sometimes implies, but of a single family’s trauma and the ways it supposedly—though not always convincingly—shaped their lives. By the end, we don’t have a picture of who the Fletchers are but rather a picture of what they have suffered, and the book seems to be saying that these are the same thing: You are your hardships. It’s an old idea, but is it true?”

–Erin Somers on Taffy Brodesser-Ackner’s Long Island Compromise (The Nation)

“All of this raises the question of whether Tulathimutte’s deeper subjects, beyond the plight of the rejected and the warping dynamics of online pseudo-life, aren’t the limits of realism and fiction itself. He has written elsewhere that ‘the rejection plot’ necessarily involves the counterfactual because the reject is in mourning for a life that never happened and will never happen. Throw in the element of online fantasy and that puts us at a triple remove from the real. Philip Roth wrote of American novelists in 1961 that ‘actuality is continually outdoing our talents, and the culture tosses up figures almost daily that are the envy of any novelist.’ He was talking about characters and events you could read about in the newspaper, hear about on the radio, or see on television. The internet tries to outdo itself every day, and tosses up many figures hour after hour we will soon enough forget and may wish we’d never heard about in the first place. Tulathimutte is aware of this disposability but has nonetheless written a book full of memorable characters. He has put his book in direct competition with the fecund but also vacant online world that is also one of its subjects. He’s aware that the version of the internet he portrays and its significance have been temporary, essential really only to his generation, the millennials, whereas for Generation X (like me) it was never ‘real’ and for the Zoomers—they have TikTok or whatever…It’s curious that Rejection, a comedy of anti-manners, is the dialectical opposite of the novels of the current most popular anglophone novelist of manners: virtuosic and maximalist on the prose level instead of plain and spare, ironic and cynical in its treatment of politics rather than earnestly gestural, unyielding to fantasies of romantic fulfillment and happy endings. For once, the Americans are more fucked up than the Irish.”

–Christian Lorentzen on Tony Tulathimutte’s Rejection (Bookforum)

“Yet Horse Crazy is one of the best American novels about obsession in part because the narrator mostly dislikes Gregory, subjecting this object of lust to the same derisive interior voice that comments on virtually every other aspect of his life. His pristine exterior notwithstanding, Gregory personifies the very elements that make the book’s protagonist want to retch: He is an ascendant photographer whose fussy, expensive prints are sourced from pornography magazines (to which he expresses a moralistic opposition that exasperates the narrator). He is extremely articulate, yet much of what he says is fatuous and clichéd, informed by undigested pop psychology picked up seemingly through the osmosis of youth. The narrator detests Gregory’s music tastes, his artistic opinions, and, after sufficient exposure, his charm. He admits to enjoying Gregory’s personality only during a shopping expedition at a Salvation Army, where the younger man picks out grotesque garments and then reveals that he chose them precisely for their hideousness—he wants to offend the sensibilities of the restaurant where he waits tables. Carried away by a rare gust of sentimentality, the enamored narrator brushes some freshly fallen snow from his beloved’s hair.

Love, in Horse Crazy, is transactional, one-sided, unconsummated, and cruel; it pushes Indiana’s fictional stand-in out of dreamy solitude and into the savage present. The insufferable facets of Gregory’s personality are reflections of Indiana’s city and era.

…

Gregory’s judgmental perspectives on sex comically echo the culture wars raging in the United States when Horse Crazy was published. If the novel’s narrator, and perhaps Indiana himself, found these things alternately tiresome and foreboding, they also drew him out of his life and his walls of books, offering the vague promise that he could be a lover and not an observer—which is to say, that he could be less like himself.

But Horse Crazy, like much of Indiana’s output, avoids a thoroughgoing cynicism even as it disregards affection as ‘the mortal illness of lonely people.’ Indiana diminished concepts such as love and hope not because his life or his work lacked them, but because he didn’t want these nebulous formulations to be used as Band-Aids on chronic societal problems and symptoms of the human condition. In Horse Crazy, his implacable skepticism forces the reader to consider the alienating effects of an era characterized by lethal STIs, unrepentant capitalism, bulldozed cultural history, and pervasive substance addiction. The book’s true love affair is with what cannot be reclaimed: a world untouched by disease and unspoiled by money. Indiana’s idea of being truthful was to react exactly the way his epoch needed him to. The withering vestiges of avant-garde New York—the writers, critics, artists, filmmakers, and dancers who have hung on since its peak—feel a little less vital today without his contempt.”

–Daniel Felsenthal on Gary Indiana’s Horse Crazy (The Atlantic)

“To paraphrase Rick Blaine’s description of Captain Renaud in Casablanca, Sadie is a typical Kushner character, only more so. Like Reno in The Flamethrowers, she knows her way around mechanical devices and combustion engines; a motorcycle appears on the first page of Creation Lake as if it were the gun on the wall in Chekhov’s famous maxim. Like the intriguer and burlesque dancer Rachel K in Telex from Cuba and the street-smart stripper Romy Hall in The Mars Room, Sadie is unsentimental and transactional about romance and sex, which is sometimes an unpleasurable drawback (as when she has to go to bed with Lucien to keep her cover) and sometimes a fun perk (as when she gets to bang René, one of the Moulinards) of her line of work. She is also an inveterate explainer of the way things, people, and places work, the product of a writerly imagination that likes to leave as little of her meticulous research—whether it is into the United Fruit Company, Brazilian rubber manufacture, prison moonshine production, or pseudoscientific Japanese blood-type personality theory—on the cutting-room floor as possible.

In Creation Lake, Kushner reduces the multiple narrative perspectives of her previous novels to a single first-person narrator. Espionage is an ideal profession for such a narrator to have. Believably partial (in accordance with standpoint epistemology) and believably omniscient (in accordance with surveillance capitalism), the spy is a worthy successor to that defunct three-letter agency, God. But with hard-boiled Sadie, Kushner dials up the cynicism to eleven. She makes Sadie so ostentatiously unlikable, it is as though she were less interested in creating a believable character than wading editorially into the debate that surrounded Nora Elridge, the protagonist of Claire Messud’s The Woman Upstairs, published in 2013, the same year as the events recorded in Creation Lake.

…

There are, of course, literary pleasures to be had in a sociopathic protagonist. However, unlike the more ingenuous and self-doubting anthropology grad student who travels to Botswana to join Nelson Denoon’s matriarchal commune in Norman Rush’s Mating, Sadie’s cynicism inoculates the reader of Creation Lake against running the risk of falling under Pascal’s spell.”

–Ryan Ruby on Rachel Kushner’s Creation Lake (Bookforum)

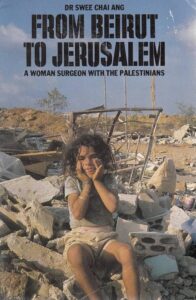

“Ang, an orthopedic surgeon, provides an eyewitness account of the Sabra and Shatila massacre of 1982. Her experience and everything that followed exposed her to the limitations of medicine emptied of politics and of doctoring—tending to one person at a time—while facing a death machine. Rereading From Beirut to Jerusalem now, I’m struck by how little Israel’s conduct, including its targeting of medical infrastructure, has changed in the past forty years. The intentions—which can be distilled as the elimination of a people—are consistent, the means updated to fit the technology of the day. I’m struck too by how rare a voice like Ang’s remains, how few doctors are willing to articulate the intentions to which the bodies they tend testify.

…

Over seventy-two hours, the majority of which Ang spent operating underground, at least fifteen hundred Palestinians were slaughtered in what came to be known as the Sabra and Shatila massacre. Israel denied direct involvement. When Ang returned to the camps, decaying bodies lay everywhere. She remembered the children who had clung to her at the hospital, perceiving her as a kind of anchor. These children had called her a ‘brave doctor.’ But she was ‘merely uninformed. Anyway I had been working so hard that I had no time to be afraid.’ Her final patient, before the soldiers came and took her, was an eleven-year-old boy with three gunshot wounds. He had spent hours trapped under twenty-seven bodies of people who loved him, and whom he loved in return, until his friends searched through these bodies to find him, alive, then risked their lives to bring him in to seek care.

…

Ang dismissed a practice of medicine that refused to consider the world. If, by attending to the political, she should be accused of compromising her ‘objectivity’ as a doctor, then so be it. For her Palestinian colleagues, a detached approach had always been nonviable. During the Israeli assault on Beirut, medical staff began referring to the symptoms of children suffering shell shock, physical trauma, and whose families had been murdered, collectively as ‘Reagan-Begin syndrome.’ They had to go upstream to describe the actual etiology of the harm. In October 2023 doctors in Gaza coined a chilling abbreviation to fill an unprecedented semantic need: WCNSF, ‘wounded child, no surviving family.’ What’s a child’s family to do with their healing status? Well, everything.”

–Mary Turfah on Ang Swee Chai’s From Beirut to Jerusalem (Bookforum)