Our fabulous five this week includes Patricia Lockwood’s gloriously acerbic assessment of the oeuvre of John Updike, Jonathan Lethem on a self-portrait of Edward Snowden, Chris Nashawaty on the story of a man inside Jimmy Hoffa’s shadow, Sloane Crosley on Leslie Jamison’s journalistic battle between sentiment and detachment, and Dan Chiasson on Fanny Howe’s latest collection of poetry.

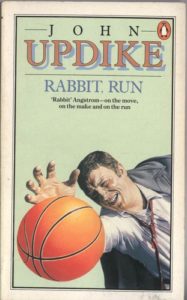

“I was hired as an assassin. You don’t bring in a 37-year-old woman to review John Updike in the year of our Lord 2019 unless you’re hoping to see blood on the ceiling. ‘Absolutely not,’ I said when first approached, because I knew I would try to read everything, and fail, and spend days trying to write an adequate description of his nostrils, and all I would be left with after months of standing tiptoe on the balance beam of objectivity and fair assessment would be a letter to the editor from some guy named Norbert accusing me of cutting off a great man’s dong in print. But then the editors cornered me drunk at a party, and here we are … No one can seem to agree on his surviving merits. He wrote like an angel, the consensus goes, except when he was writing like a malfunctioning sex robot attempting to administer cunnilingus to his typewriter. Offensive criticism of him is often reductive, while defensive criticism has a strong flavor of people-are-being-mean-to-my-dad … This is what Rabbit is: a carnal pleasure, something Updike has more than allowed himself. In the end he will not deny his character anything…When he is in flight you are glad to be alive. When he comes down wrong—which is often—you feel the sickening turn of an ankle, a real nausea. All the flaws that will become fatal later are present at the beginning. He has a three-panel cartoonist’s sense of plot. The dialogue is a weakness: in terms of pitch, it’s half a step sharp, too nervily and jumpily tuned to the tics and italics and slang of the era. And yes, there are his women … How am I to write about all of him, see him from every angle? It is helpful to visualise a globe: here are deserts of incomprehension, and here glaciers of stopped sympathy, and here a warm hometown seen right down to the brushstrokes.”

–Patricia Lockwood on Novels, 1959-65: The Poorhouse Fair; Rabbit, Run; The Centaur; Of the Farm by John Updike (The London Review of Books)

“Permanent Record is an attempt to reverse the binoculars and offer a self-portrait of the man—whistleblower? leaker? dissident? spy?—who walks the earth, these days in Moscow, under the name Edward Snowden. Snowden might seem forever defined by a single act—his decision to leak highly classified information copied from the NSA—and a single moment in time. Having gazed through the windows of the panopticon, he experienced that rarity, a moment of vision: The world must be told these things I know. Against absurd odds, he delivered his knowledge to us. Now he proposes to explain to you, by first explaining to himself, how he became (both how he was formed, and why he chose to become) the person playing this watershed walk-on part on the recent historical stage … Do we need a memoir by a person who proposes that ‘the more you know about others, the less you know about yourself’? Perhaps, if we grant that Snowden’s difficulty may not be the exclusive province of spies, but rather embodies a characteristic fissure in contemporary selfhood … If you choose to believe this memoir—I do—then that same unironic patriotic nerve drove each subsequent phase of Snowden’s disillusionment, and what followed: the iconoclastic deed that propelled him to fame … What a strangely ordinary man: Snowden’s either the least enigmatic cipher or the most gnomic nonentity ever to live. You could watch him study himself forever.”

–Jonathan Lethem on Edward Snowden’s Permanent Record (The New York Review of Books)

“Nearly 45 years after his vanishing act, Hoffa’s infamous fade to black still enthralls, digging its meat hooks into our collective, true-crime-loving psyche. It remains one of the most notorious unsolved mysteries of the 20th century, along with the whereabouts of Amelia Earhart and the identity of the so-called second shooter on the grassy knoll. As such, it has fueled no shortage of theories about where Hoffa’s body ended up: in a vat of boiling zinc in a Detroit fender factory; as alligator food in the Everglades; somewhere beneath the old Giants Stadium in the Meadowlands, a fossil of postwar American criminality … it’s fair to say that the last thing the world was itching for in 2019 was another speculative account of Hoffa’s final days. Which is precisely why Jack Goldsmith’s gripping hybrid of personal memoir and forensic procedural lands with the force of a sucker punch. More than just another writer chewing over the same old facts and hypotheses, Goldsmith turns out to have a uniquely intimate connection to the case that gooses him along on his hunt for the truth … Some will no doubt regard Goldsmith as an unreliable narrator, but O’Brien, the man in Hoffa’s shadow, comes across as a deeply tragic figure … Goldsmith’s quest becomes less about solving a mystery than a meditation on the complicated and occasionally bittersweet love between fathers and sons.”

–Chris Nashawaty on Jack Goldsmith’s In Hoffa’s Shadow (The New York Times Book Review)

“Jamison’s journalistic battle between sentiment and detachment rages on, sometimes resulting in texture, sometimes in tedium … Without question, Jamison has impeccable taste in her own ideas, selecting fringe subjects and following them to the end of the road … If the first section is the most fully realized, the second is the most thematically rickety … Let no one accuse Jamison of living an unexamined life, but inertia can dull her points … It’s just strange that someone who has focused so much of her writing on the body—hers, other people’s—can come off as a bit bloodless, neither screaming nor burning, her descriptions vying to out-flat one another … An essay on becoming a stepmother and another on the Museum of Broken Relationships are lovely and evocative planets unto themselves … Reviews of essay collections invariably note the ‘strongest’ pieces, but Make It Scream, Make It Burn is a reminder that strength is not a catchall. If we decide strength is about structure and elucidation, then most of these essays are heavyweight boxers. If, however, strength is about persuasion, transformation or the evocation of emotion, it’s in short supply here. We are all Percival Lowell, our lives subject to the imprint of our own gaze. Stare too long at the gaze itself and it becomes hard to see what you’re looking at.”

–Sloane Crosley on Leslie Jamison’s Make It Scream, Make It Burn (The New York Times Book Review)

“Pragmatic but blessedly naïve—she calls herself ‘gullible’—Howe’s poetry takes a line-by-line approach to managing existential fear. Her work calls to mind a child’s tactics of self-soothing, like whistling in the dark … Since new in Howe’s work means late, Love and I is, in a double sense, Howe’s latest volume. It hurries to join a long and illustrious career, which, besides poetry, includes novels, stories, memoir, and short films. Approaching eighty, Howe, in Love and I, is now revisiting the earliest formative impressions of preconscious childhood, when ‘everything seemed like something else’ … Howe prefers the clarity of misunderstanding to the blur of certainty. Like stained glass, her poems await illumination, but it is important not to flood them with a klieg light … It is marvellous to think of these works as having been made not in some bower but in the midst of life. The basis of Howe’s poetry is watchfulness, as from a train window … The necessity of reimagining time even as time runs out gives this book its urgency. These poems are partly about facing old age without a partner. The title Love and I suggests old companions who have grown abstract, almost allegorical in their relations to one another, like functions in a math problem.”

–Dan Chiasson on Fanny Howe’s Love and I (The New Yorker)