This week’s quintet of quality reviews includes Hannah Giorgis on Jeanine Cummins’ American Dirt, Jia Tolentino on Kyle Chayka’s The Longing for Less, Laura Miller on Megan Angelo’s Followers, Jennifer Szalai on Jessica Stern’s My War Criminal, and Ron Charles on Paul Yoon’s Run Me to Earth.

“… a tightly integrated collection of six masterfully written stories … Yoon’s perspective shifts nimbly from one teenager to another, catching the currents of delight, confusion or terror flitting through this ‘orbit of chaos’ … We know, of course, how impossible that modest dream is for these three young friends working in the most dangerous spot on Earth. But Yoon’s narration is so closely pared, so free of excess drama that when violence rips through these lives, it feels especially shocking. In a sense, he’s re-created the psychological experience of battle: the weird interludes of happiness and boredom suddenly shattered by incomprehensible disorder … Individually, the chapters exercise hypnotic intensity, but the overall effect is even more profound. With his panoramic vision of the displacements of war, Yoon reminds us of the people never considered or accounted for in the halls of power … Yoon makes us care deeply about these adolescents and what happens to them. For all that he eventually reveals, some details are forever dropped between the shifting plates of survivors’ memories. That’s cruel, but like everything else here, entirely true to the lives of people scattered by war.”

–Ron Charles on Paul Yoon’s Run Me to Earth (The Washington Post)

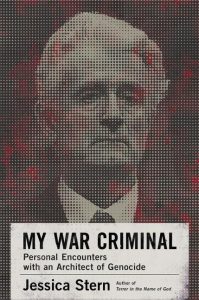

“What happens when an author tries so strenuously to empathize with her subject that she loses control of her own book? … It’s a question that kept coming to mind as I read My War Criminal … The problem with My War Criminal is that Karadzic—a psychiatrist who wrote bad poetry before becoming the president of Bosnia’s hard-line Serbian nationalist party—apparently knows enough about her determination to write a book about him to turn her own method against her. Karadzic gets fashioned here into the charismatic character Stern so clearly wants him to be … During the conversations, she deliberately avoided challenging Karadzic in any way … Stern inflates the drama of her narrative … More disconcerting than the awkward literary affectations is how Stern writes about the actual history of the war. Stern says she isn’t trying to deny a genocide, nor is she trying to redeem Karadzic. But in her attempts to ‘follow his moral logic,’ she entertains his tortured excuses and grotesque fantasies … It’s exasperating to watch a smart woman play possum like this—not just in the interviews but in the writing, especially when her conclusions don’t tell us anything we didn’t know before.”

–Jennifer Szalai on Jessica Stern’s My War Criminal: Personal Encounters with an Architect of Genocide (The New York Times)

“…a new book by the journalist and critic Kyle Chayka, arrives not as an addition to the minimalist canon but as a corrective to it … Along the way, he offers sharp critiques of thing-oriented minimalism. The sleek, simple devices produced by Apple, which encourage us to seamlessly glide through the day by tapping and swiping on pocket-size screens, rely on a hidden ‘maximalist assemblage’ … His dual response to the all-white apartment is one of the only moments in The Longing for Less when Chayka acknowledges his attraction to superficial minimalism, but that attraction pulses throughout the book. The writing has a careful tastefulness … In a way, Chayka’s book replicates the conflict he’s attempting to uncover—between the security and cleanliness of a frictionless affect and the necessity of friction for uncovering truth. He does have moments of productive discomfort … Chayka best conveys the unnerving existential confrontation that minimalism can create in his capsule biographies … This is, in the end, the most convincing argument for minimalism: with less noise in our heads, we might hear the emergency sirens more clearly.”

–Jia Tolentino on Kyle Chayka’s The Longing for Less: Living With Minimalism (The New Yorker)

“…works like American Dirt, which labor to provoke empathy in an imagined audience—one that shares far more in common with the author than with the characters—are limited by the impossibility and soft egotism of their aims … Cummins’s novel actually offers little by way of actionable material. Instead, it inspires empathetic despair in a hypothetical American reader. Along with the rapturous praise that first accompanied it, the book encourages comfort with this facsimile of justice alone. What good, after all, does the mere acknowledgment of migrants’ essential humanity do for those whose lives have been shattered—and in some cases, ended—in large part because of punitive U.S. immigration policies? Are the tens of thousands of migrant children held in government custody, some of whom never see their families again, to feel comforted by American Dirt’s limp exhortation to the average reader—or by Oprah Winfrey’s selection of the novel for her famed Book Club? For those whose lives are not shaped fundamentally by the indifference of others, empathy can be a seductive, self-aggrandizing goal. It demands little of author and reader alike … Cummins has largely dismissed the concerns of real-life authors ‘browner’ than her, insisting that her book alone is not responsible for the publishing industry’s entrenched racism. This is, of course, true. But her responses have nonetheless underscored the pernicious and widespread belief that won American Dirt fanfare in the first place: that ’empathy’ exists for the benefit of the spectator, not the afflicted.”

–Hannah Giorgis on Jeanine Cummins’ American Dirt (The Atlantic)

“Orla—one of the main characters of Megan Angelo’s dark, witty, and astute debut novel, Followers—is as archetypal a young heroine for an early 21st-century novel as Bridget Jones was for the literary rom-coms of the late 1990s. But while Bridget’s goals—to lose weight, meet a nice guy, get married—seem innocuous in retrospect, Orla’s hankerings poison her life. Followers is no romantic comedy, and Angelo clearly doesn’t mean it to be, but it’s a satire in which scraps of optimism drift down the streets of Manhattan like torn and trampled flyers … Yes, there’s an element of dystopian science fiction to Followers, but if you expect the novel to detail how exactly the free-range internet collapsed, who caused the Spill, and what the broader social consequences of the event were, you’ll be disappointed. Instead, Angelo stays focused on how communications technology affects young women and their most intimate relationships. Marlow’s world, despite the mystery of the Spill, is a logical descendant of our own, in which the call to ‘come watch these beautiful people be on camera all the time’ is used not to sell ads but to rebuild a digital public life … This is Angelo’s most original twist, to suggest that the outrageous fakery of Flosstown Public did produce something genuine, something the novel’s characters will end up chasing to a most unlikely yet winning conclusion. Is there a moral to this story? Probably not. And that’s the realest thing about it.”

–Laura Miller on Megan Angelo’s Followers (Slate)