One of the greatest challenges facing writers today—when our species has killed off the vast majority of lifeforms which share the planet with us—is how to tell stories which center nature. For too long the natural has been window dressing—a glimpse of calm, the mysterious living thing which soothes.

This dominant idea of nature has often been a fig-leaf for dominion, for a notion that nature is there to be used as a resource, and that our responsibility to it can be sold through self-preservation. As in, we cannot use up this precious resource. Or: pity. As in, let us listen to it sing its elegy.

What would nature sound like if we did a better job of listening to it, of paying attention? If we tried to learn its knowledge systems—or at least imagined them? The vast majority of scientists agree that the planet and its vast ecosystems are under a grave threat, from us. It cannot speak our language back to protest. But it does speak.

Examples of how to listen in literature date back to the beginning of time—Ovid and Shakespeare were clearly fascinated by the limits of being human. Tempests, floods, planetary disturbances, and the mysterious will of nature ripple through their work. Yet nature doesn’t simply speak in a tumult—that is often the only time humans feel it.

In the poetry of Louise Erdrich, Ursula Le Guin, and Arthur Sze on the North American continent the natural is often given equal footing to human design. Its rhythms, migrations, and simple existence paces and places their books, the interplay between the wild and the human create a new space: one which raises moral questions about co-existence.

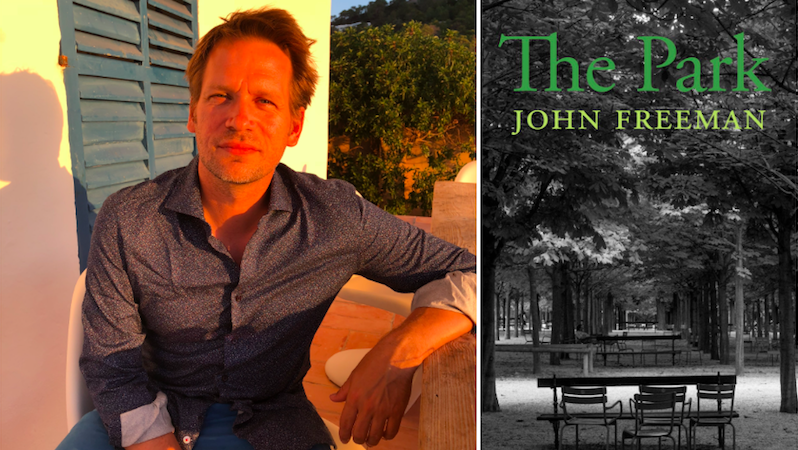

When I was writing the poems in my latest book, The Park, set around four seasons in a park in Paris, I looked for other models of how a collection made and seen by a human can co-exist with the natural. Here are some books and poets I found along the way, writers who shone like beacons to me in this challenge to map what was in front of them, rather than a fantasy or worse yet, a bad dream.

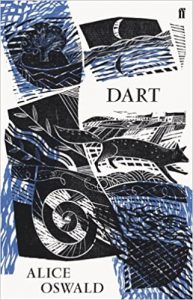

Dart by Alice Oswald

The English poet Alice Oswald spent three years speaking to people living along the river Dart, and then composed this miraculous little book. In sonic terms, it reads like an oral history of a river’s journey to the sea, in which the mutterings of those who live and work alongside it blend with the sounds the water makes. Gods and demons make appearances, as do the wildlife which draws life from its banks. Dart, Oswald reminds, is old Devonian for oak, and as the book proceeds it assembles a lexicon of itself; the river squelches and oozes by, it is a “foundry for sound.” Meanwhile, time flows in eddies and currents. This book feels at once eternal and like yet another leaf carried downstream in humble perfection.

Poūkahangatus by Tayi Tibble

Tayi Tibble’s remarkable debut collection takes its title from a fictional, hybridized Māori word paying tribute to Pocahontas of the Powhatan tribe, a move which prefigures the many ways she rewrites myths in the book—from that of Medusa to the founding tales of the nation of New Zealand. Veering from high camp to exquisite lyric, the book was a sensation upon its publication two years ago in Wellington, where Tibble lives. It’s not hard to see why—the book’s range of sounds and forms is simply awesome. It also demonstrates the power of all paradigm shifting books—which is to fold up previously knotty stumbling blocks like they are furniture left out in the rain, and then replace it with an enlarged space. As a Te Whānau ā Apanui / Ngāti Porou woman, Tibble writes here, she does not feel a division between her body and the land which was colonized by settlers. “I developed an early kind of kinship/with all the ways the earth hurt,” she says, “With a toy stethoscope and that lavalava/I nursed wounds that made me wobbly/and only half visible, like a mirage.”

TEOTWAWKI by Lars Skinnebach, translated by Susanna Nied and others

I’ve only been able to read selected translations from this as yet untranslated award-winning volume by Skinnebach, who writes in Danish, but what I have read is harrowing and strange, luminescent with freshness. In Skinnebach’s poems humans appear in voice and behavior like the Patrick Bateman of the natural world, scissoring through space with cavalier sadism. “And when the ants came/I followed them down/underground where they lived/blocked their exists/and plundered the nests,” goes one, in Susanna Nied’s nimble translation: “and plundered their stores/minerals, eggs and dust/minerals, food and knowledge/and poured saliva into their saliva.”

The Selected Poems of Tu Fu, translated by David Hinton

Many of the greatest poems which are attributable to the 7th century Tang Dynasty poet Tu Fu were written in the last decade of his life, in a tumultuous time like our own, the poet on the move, a migrant, his civil service post abandoned, a new era of idiocy reigning in the capital. In Tu Fu’s case, it was the An Lushan rebellion, which sent he and his family into exile, and in 766, he spent two years at the mouth of the Three Gorges and wrote several hundred poems in a new late style. Where his previous poems could be confused with the work of Li Po, these seething, embroidered new lines are all his own. Nature is not metaphor, but reality’s foundation. “All day long, dragons delight,” he writes on one muggy, misty day: “swells coil/and surge into banks, then startle back out.” The descriptive challenge to a poet of simply observing the natural is in some cases more than enough, and sometimes it can create a two way door from society into nature and back into a society teetering on the brink of war, as in “Leaving the City”:

Leaving the City

It’s bone-bitter cold, and late, and falling

frost traces my gaze all bottomless skies.

Smoke trails out over distant salt mines.

Snow-covered peaks slant shadows east.

Armies haunt my homeland still, and war

drums throb in this far-off place. A guest

overnight here in this river city, I return

again to shrieking crows, my old friends.

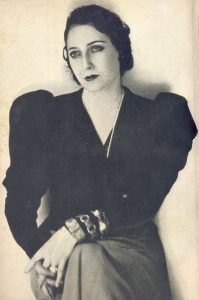

Juana de Ibarbourou, selected poems

The Uruguayan poet Juana de Ibarbourou, who died in the late 1970s, is, like Skinnebach, sparsely translated, but several poems of hers crossed my desk somehow ages ago and I found them impossible to forget for the way she shattered the human/nature divide, usually in writing of love. “What is it?” she writes in one, “a miracle, my hands are in bloom./Roses, roses, roses.” What an incredible way to think of passion, for it’s not clear if the poet has become a flower, if she is holding a flower, or is likening herself to the flower. In every single poem I have read by Juana de America (as she is sometimes called) nature is centered in and through the body, our senses, the way most of us—in the best of times—turned toward the light, the way a plant bends toward it.

*

John Freeman’s The Park is out now from Copper Canyon Press