Kerri Arsenault, the author of Mill Town: Reckoning With What Remains, recommends five books that altered her thinking on how a story can be told.

Dictionary of the Undoing by John Freeman

“We all need language to be as specific as possible” Freeman writes in the last lines of his A to Z assessment of the assault on language itself. Words are the basic unit of storytelling and if the possibilities within them are deflated, then the stories we tell are equally as empty, and if our stories are empty, so is our culture. In Dictionary, Freeman injects new life into not just words, but a new way of thinking about meaning, about what words carry, about how we deploy them, and how we can reinvigorate them to incur positive change. Two things undergird the whole operation: one, Freeman is optimistic (even when he’s discouraged) that words can make the world a better place and two, the structural integrity of how he pulls this critique off. Beginning with “Agitate” he builds upon each new letter/definition to incorporate the last, so that by Zygote, then entire alphabet is anew. He puts each letter together, one by one until they form words, sentences, paragraphs until the smallest unit is subsumed elegantly (seamlessly) by the larger whole. This is not just an intellectual exercise—it’s a book with a big heart: “Optimism is not a form of naivete; it’s a necessary wedge of anticipation, hope says to us, It would be nice if this happened; optimism replies, with its flicker of light, I really think it might.” I keep Dictionary close at hand, as it reminds me with its big red letter “A” on the cover that storytelling begins with just that: one letter.

The Peregrine by J. A. Baker

Where Freeman stands on the three point field goal line of meaning, symbolism, activism, structure, Baker just useswords and I’m perennially inspired his prose. Whenever my writing lacks focus or feels dull, I peel open a random page. Example: “The field was silent, misty, furtive with movement. A cold wind layered the sky with cloud. Sparrows pattered into dry-leaved hedges, rustling through the leaves like rain. Blackbirds scolded. Jackdaws and crows peered down from trees.” Yeah, that’s right. That’s a random page of Baker’s book about following a peregrine around the fenlands of the English countryside fall to spring. In this semi-plotless book, I found not just beauty, but, peace, respite, even if I was reading about the cycles of life and death, of the metamorphosis of man and bird, or the “atmosphere of requiem” as Rob Macfarlane writes in the introduction. It is beautiful, even in its sloped sadness, the kind that comes with a late August light in New England. That’s not to say this is a typical “nature” book, with Baker’s ruminations about his place in it. Nope. This is pure poetic elegy about land, obsession without compare, and the daily ignitions of a bird. I invite you to let a page fall where it may and you just might find something like “They flew languidly up, moving reluctantly, slowly, like cattle making way. Their whiteness was made wraith-like, unsubstantial, by the white gleam of the snow.”

The Jungle by Upton Sinclair

I was seventeen, idealistic, mad. Then I read The Jungle, Upton Sinclair’s indictment of the meatpacking industry as told through Lithuanian immigrants working in Chicago’s slaughterhouses. I got madder. Not only did it make me want to be a writer, it showed me that storytelling could change the world. The book (the same exact book; see photo) stuck with me and I still read passages any time I feel a lapse in hope or in outrage because Sinclair needed (and had) ample amounts of both to reach the halls of legislative debate about food laws.

I wasn’t much of a reader as a child, even though I was good at it (my sister taught me to read when I was four), and I never stepped foot in our public library. I poached adult novels, like Looking for Mr. Goodbar, from my parents’ beside tables, or read my father’s monthly Esquire or Playboy interviews. Although those texts seem racy for a preteen girl, it was Sinclair’s book that excited me most. Those visceral sentences, the character descriptions, the canned horsemeat, the environmental impact, the public outcry, the injustice, that scene about the sausage making, the precision of his words, and the blood that flowed like the depravity that fueled it. Sinclair used writing to right wrongs, which is what I think books can and should do.

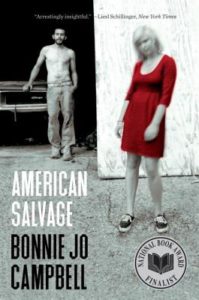

American Salvage by Bonnie Jo Campbell

Two things Campbell’s short story collection schooled me on: how to tell stories about people in the periphery of America’s post-industrial landscape and how to craft and the importance of a sound landscape in text alone. First, she never devolves into sentiment or judges her characters. They are displaced people, struggling to make their way. The book is still resonant, as the rich get richer and the poor get poorer with each passing day. With the background of a one crop economy (largely, the automotive industry) and people who work with their hands, this book also said to me, these stories are worth telling. In “The Inventor” she writes “His burns were a pact the foundry made with him,” which is saying this guy made a deal with the devil, one so many blue collar workers make in industries that are dangerous but necessary to their lives.

Second, the sounds of American Salvage are so critical to understanding the landscapes of where these stories take place. Campbell recreates that hum of industry and machines, the sound of work in everything she describes. In “World of Gas,” we hear the whir of a dishwasher, ATM machines, traffic lights, computer systems, automobile engines, the highway, “the buzz of an airplane flying overhead, the muted din of shift work at the paper factory” all orbiting around Pur-Gas, the company where the main character works, a play on purr, which is what machines do. It’s white noise, the kind of sound I heard as a kid when our paper mill lullabied me to sleep.

Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor by Rob Nixon

Nixon’s like, let’s change storytelling altogether. This is the foundation of how I look at environmental disasters like toxic pollution, climate change, the ubiquity of plastics, and how narratives can reflect those kind of disasters. In fact, this book revised the definition of the word “disaster” entirely for me.

Nixon uses the term “slow violence” to describe how these type of environmental events occur “gradually and out of sight, a violence of delayed destruction that is dispersed across time and space, an attritional violence that is typically not viewed as violence at all.” The kind of disasters that happen in the slow tick of time not spectacularly like hurricanes or earthquakes, both of which make far better TV. While neither type of disaster is welcome, it’s these more invisible ones that are hard to pin down and if they are hard to pin down, they are harder to fix or deter. Nixon combines a critique of modern environmental literature, an examination of our “inattention to calamities that are slow and long lasting,” and indicts power brokers who offload their global toxins onto the poor of the world. This book is ballast to a listing ship of environmental storytelling and to the impoverished people who act as recycling units to the shit industry coughs up.

*

Kerri Arsenault is the book review editor for Orion Magazine and contributing editor at Literary Hub. Her new book, Mill Town: Reckoning With What Remains is out now from St. Martin’s Press.