Finalists for the National Book Critics Circle John Leonard Award for best first book in any genre are Lesley Nneka Arimah’s What It Means When a Man Falls from the Sky, Julie Buntin’s Marlena, Zinzi Clemmons’ What We Lose, Layli Long Soldier’s Whereas, Carmen Maria Machado’s Her Body and Other Parties, and Gabriel Tallent’s My Absolute Darling. The Center for Fiction First Novel Prize goes to Julie Lekstrom Himes’s Mikhail and Margarita.

Sam Shepard’s last book is “Godot in the desert,” Mary Beard writes a “sparkling and forceful manifesto,” Sylvia Plath’s letters show her to be so much more than a “suicide writer,” Ursula Le Guin collects essays from her blog, and Gerrick D. Kennedy gives us a history of N.W.A.’s “ghetto noir.”

Sam Shepard, Spy of the First Person

This slim volume from the revered playwright, actor, and fiction writer was written during the final months of his life, with help from his family and his friend Patti Smith.

Heller McAlpin (Barnes & Noble Review) writes:

The first words of Sam Shepard’s remarkable, quietly devastating last book, written in the final year of his life when he was dying of ALS, let us know what he’s up to: “Seen from a distance.” In Spy of the First Person, Shepard, a restless wanderer trapped in a failing body, squeezes himself through an escape hatch by doing one of the things he’s always done—writing. He objectifies himself, putting distance between his corporeal and mental selves by splitting alternately into observed and observer in order to report on his predicament from afar. One of many searing observations: “The more helpless I get, the more remote I become.”

Elisabeth Vincentelli (Newsday) calls Shepard’s last work “a testament-like fever dream of autofiction. Loosely structured, to say the least, it is not the easiest thing to label, and not the easiest thing to read, either. Those new to Shepard’s world may not want to start here, but his fans may find the elegiac tone haunting.”

Jocelyn McClurg (USA Today) writes, “There are references in Spy of the First Person to his actual sisters and two sons and daughter, so reality fleetingly intrudes upon this fragmentary, disjointed narrative, in which Samuel Beckett’s influence on Shepard (Buried Child, Fool for Love) has perhaps never been more apparent. It’s Waiting for Godot in the desert.”

Colette Bancroft (Tampa Bay Times) calls Shepard’s swan song “spare but not slight, surreal yet stoic, an intriguing and moving glimpse into what falls away and what still matters at the end.”

Mary Beard, Women & Power: A Manifesto

The Cambridge classicist’s new book is slim and potent.

Parul Sehgal (New York Times) calls Women & Power a “sparkling and forceful manifesto.”

Julie Phillips (4Columns) writes:

Women & Power, originally two lectures given in 2014 and 2017, begins with the compelling observation that at the opening of the Odyssey, right at the start of the Western literary tradition, is a scene of a man telling a woman to shut up. The woman is Penelope, whose son Telemachus informs her that “speech will be the business of men, all men, and of me most of all; for mine is the power in this household.”

“What can the myth of Medusa tell us about classical myth, perceptions of female power and sexism from antiquity to today?” asks Sarah Bond (Forbes). “The roots of misogyny can be traced back to antiquity.”

The Letters of Sylvia Plath, Vol. 1, ed. by Peter K. Steinberg and Karen V. Kukil

Plath’s letters “reveal an ambitious writer, a well-read intellectual, a dedicated wife and mother and a sensual woman with a highly developed sense of humor,” co-editor Kukil tells Ms. Magazine’s Aubrey Menarndt. “Indeed, by making Plath’s work available for mass consumption, Kukil promotes Plath as more than just a ‘suicide writer’—and gives voice to her intelligence, humor and passion.”

Hamilton Cain (Minneapolis Star-Tribune) notes, “From an early age, poet Sylvia Plath (1932-1963) was a prolific letter writer, dashing off various missives and postcards each day to the people whose lives brushed against hers. Volume I of her collected letters arrives like a doorstop, tapping well-known archives and unearthing fresh specimens. The result is a comprehensive if repetitive portrait of the artist as a young woman, ardently—unnervingly—committed to literature and relationships.”

Rachel Cooke (The Guardian) calls out the 16 love letters Plath wrote to Ted Hughes in 1956, the year they married, published here for the first time. “These extraordinary dispatches are born of sexual passion, a wave that Plath—you sense this instantly—has not ridden before. When she is with Hughes, no night is too long, no day without its radiant possibilities. Away from him, she is utterly debilitated, a rag doll on a floor. This is not peace. As we know, it will never be that. But the ‘law courts’ that were once permanently in session in her head, whispering the flaws of every man she met, have at last fallen silent—and it’s impossible, as she toils to explain this, not to be thrilled for her. For a few spellbinding moments, her incandescent sentences snaking on and on, the dreadful apprehension of what lies ahead is all but forgotten.”

“Engaging and revealing, The Letters of Sylvia Plath offers a captivating look into the life and inner thinking of one of the most influential writers of the 20th century,” concludes Paul Alexander (Washington Post).

Ursula K. Le Guin, No Time to Spare

Le Guin’s blog ranges widely, as proven by these samples.

“No Time to Spare, deriving from Le Guin’s online essays, covers just about anything that crosses her mind, from ‘lit biz’ to cats to the Oregon landscape,” writes Michael Dirda (Washington Post). “Still, old age, sexual and national politics and our dismal future predominate.”

Maria Popova (Brain Pickings) gloms onto Le Guin’s section on anger, noting that “anger, like silence, is of many kinds and thunders across a vast landscape of contexts, most of its storms ruinous, and some, just maybe, redemptive. That is what the sharp-minded, large-spirited, incomparably brilliant Ursula K. Le Guin examines in an essay titled “About Anger,” found in her altogether fantastic nonfiction collection No Time to Spare.

Michelle Dean (Los Angeles Times) concludes, “Because at the end of No Time to Spare, having enjoyed all the Annals of Pard and the Steinbeck anecdotes, the stories about the Oregon desert and the musings on belief, all I could think was: I want Le Guin to keep going, on and on. I want to read more. But of course, in a blog post, there wasn’t time for that.”

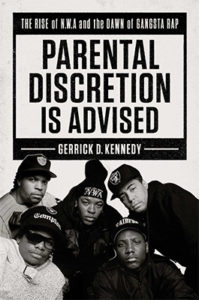

Gerrick D. Kennedy, Parental Discretion Is Advised: The Rise of N.W.A and the Dawn of Gangsta Rap

Tirhakah Love (Los Angeles Times) sets it up:

Kennedy’s book caps off a 25th anniversary of the moment hip-hop’s political utility became fully realized in the wake of the L.A. riots. Within a problematic mix of Afrocentricity and brutality, of testosterone and lawlessness, black men were awakened by one another’s struggles to live in peace under the hand of the LAPD. The story of Ruthless Records is the story of Compton in a blazing rage; it’s the story of black independent business undone, internally, by the very forces it sought to fight off: betrayal, backbiting and a trickle-down business practice that saw adroit hip-hop lifers like D.O.C. and Ice Cube receiving the short end of the stick—at least early on.

The Associated Press weighs in: “Kennedy points out all the major landmarks fans already recognize—to your right, the ‘sonic Molotov cocktail’ of an album, 1988’s ‘Straight Outta Compton,’ and to the left, the dismayed reactions of radio stations, TV networks, politicians, parents and more to N.W.A.’s ‘ghetto noir.’The information isn’t necessarily new. But the history, geography and smatterings of minutiae that Kennedy shares along the way makes his chronicle of N.W.A. shine.”

Stephanie Topacio Long picks the book for Bustle’s best December nonfiction books. “It looks at their many highs and lows, controversies and successes, as well as their lasting impact,” she writes.