Costa Book Award winners include Jon McGregor’s Reservoir 13 (fiction), Gail Honeyman’s Eleanor Oliphant is Completely Fine (first novel) and Helen Dunmore’s Inside the Wave (poetry), awarded posthumously to what the judges call “an astonishing set of poems—a final, great achievement.” The Story Prize judges announce three finalists this morning; this year’s winner will be chosen by judges Susan Minot, Walton Muyumba, and Library Journal’s Stephanie Sendaula. (Full disclosure: I’m on the Story Prize advisory board.) One of the many cool things about The Story Prize (in addition to its $20,000 prize for the winner and $5,000 each for the two finalists) is the TSP blog, open to posts by all those who entered (47 so far among the 2017 entrants).

Michael Wolff’s Trump takedown takes the White House (and the globe) by surprise, Ali Smith’s timely Winter draws cheers, Jamie Quatro’s first novel echoes themes in her story collection I Want to Show You More, The Perfect Nanny comes with warnings to mothers of young children, and more applause for Neel Mukherjee.

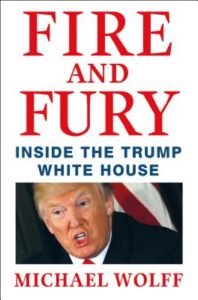

Michael Wolff, Fire and Fury

The first big book of 2018 arrives on January 3. As the East Coast hunkers down in a record-breaking blizzard, The Guardian’s David Smith drops a bombshell, offering a sneak peak of Michael Wolff’s racy White House tell-all with the headline “Trump Tower meeting with Russians ‘treasonous,’ Bannon says in explosive book.” After publisher Henry Holt releases the book four days early on Jan. 5 in the face of a “cease and desist” order from the president’s lawyer, Fire and Fury races to the top of the bestseller list. Book critics scramble to react, creating an entertaining din on a snowbound week.

Carlos Lozada (Washington Post) tweets, “In the rare case of deadline book criticism, I stayed up much of Thursday night into Friday morning reading FIRE AND FURY, the wrote and posted a review yesterday evening.” His assessment:

But more than the insults and trolling—and frankly, what is Trumpier than a bunch of demeaning nicknames?—the most damning thing this book reveals is the extent to which the Trump team, and the president himself, were simply unprepared to govern. They did not expect to win the election, so they didn’t bother to get ready. Despite promising voters that he would start winning so much that they’d get tired of it, Trump apparently made a different pledge to Melania, who feared the disruption of her easy, sheltered existence. “He offered his wife a solemn guarantee: there was simply no way he would win.”

Saeed Jones (Buzzfeed’s AM to DM) live tweets his reading of the book on Saturday: “Just when I think I’ve adjusted to #FireandFury, I get to the next paragraph and scream all over again. Just hollered out “HELP ME, JESUS” in the middle of my apartment.”

Virginia Heffernan (Los Angeles Times) addresses the question of accuracy that’s circling around the launch:

It takes a thief to catch a thief, and Michael Wolff . . . is the ideal hustler to capture President Trump, whom Wolff describes as having a “twinkle in his eye, larceny in his soul.” Wolff, if memory serves, is similar, minus the twinkle. Gimlet eyes don’t twinkle.

Say what you will about Wolff: Unless the book is wholesale invention, something in his I’m-with-the-band swagger in the West Wing attracted awesomely sordid material from Trump’s scurvy syndicate. In John Sterling at Macmillan, the book has a masterful editor, and three fact-checkers reviewed it. So I’m betting Fire and Fury will withstand whatever charges of journalistic impropriety come at it.

Ali Smith, Winter

The second in the Scottish novelist’s proposed quartet named for the seasons, which opens in late December, elicits rare enthusiasm.

“Is it fair, or right, or even practical to start a rave review of one book—and this is absolutely going to be a rave—by asking whether you’ve already read another?” asks Laura Collins-Hughes (Boston Globe) “I promise that’s not a homework question. It’s more of a heads-up. The only preparation required to savor the Scottish writer Ali Smith’s virtuosic Winter is to pay attention to the world we’ve recently been living in, with its divisions and hardened hostilities, its whipsaw reversals of social progress made.”

Mike Fischer (Milwaukee Journal Sentinel) notes that the “stunningly original Smith again breaks every conceivable narrative rule; reflecting her longstanding affinity for Modernism, what she gives us instead is a stylistically innovative cultural bricolage that celebrates the ecstasy of artistic influence. It demands and richly rewards close attention.”

Charles Finch (Chicago Tribune) concludes:

Winter is Smith’s angriest book. “There was always a furious intolerance at work in the world no matter when or where in history,” she writes. For those of us living out this winter in fear and rage, watching Twitter, reading notifications, how dreadful and true that seems. But Smith’s brilliance is that, like Mantel, like Ishiguro, she always doubles back for another meaning. “A coming back of light,” she tells us, “was at the heart of midwinter equally as much as the waning of light.” May it be so.

Jamie Quatro, Fire Sermon

Quatro’s first novel deals with a married woman engaged in an affair while pondering the span between sex and spirituality.

Anjali Enjeti (Atlanta Constitution Journal) points out, “Quatro’s first book, the evocative short story collection I Want to Show You More, explored similar themes of sex, spirituality, betrayal and guilt, and like the collection, her prose in Fire Sermon is symphonic, erotic. Nimble passages paint vivid pictures of a woman filled with a longing for a life she feels she can never have, and elucidate how Maggie’s sanctuary, her religion, gives way to shaky ground.”

Quatro’s first book was “hot to the touch for its divine, earthly and intellectual acuities,” writes Dwight Garner (New York Times). “Reading it, you felt echoes of Flannery O’Connor and Graham Greene. You also felt: This writer, born in San Diego and now living in Georgia, is constructing a new skyscraper on the literary horizon. Quatro is here now with Fire Sermon, her second book and first novel. It’s a disappointment. At best it’s a holding pattern.”

“Ms. Quatro’s attempt with Fire Sermon is to meld a story of midlife adultery with an enquiry into the fate of religious faith in the secular world,” writes Sam Sacks (Wall Street Journal). “Maggie, a semi-lapsed Catholic going through the motions of a dutiful marriage, has found in her feelings for James something nearing the intensity of divine communion, and as the novel delves into her memories and feelings it tries to bridge two ideas: First, that Christian belief is far more rooted in sex and the body than many realize; and second, that even illicit passions contain the seeds to spiritual transcendence. It’s a daringly unguarded experiment that matches some of its overwrought silliness . . . with generous samplings of poems and sermons, as well as Ms. Quatro’s own fine turns of phrase.”

Leila Slimani, The Perfect Nanny

French-Moroccan author Leila Slimani won France’s Prix Goncourt for this novel, translated into English by Sam Taylor. Its inspiration: a headline-grabbing murder in New York City.

Maureen Corrigan (Washington Post) calls The Perfect Nanny “the ‘hot’ novel of 2018.” But she warns: “The last thing working mothers with young children need to be reading in their nanosecond of downtime is this psychological suspense novel about a ‘perfect’ nanny who snaps.”

Lauren Collins (The New Yorker) is beguiled:

A year ago, I picked up a book, Chanson Douce, that I’ve thought about pretty much every day since. I was initially drawn to it because I’d read that its author, Leïla Slimani, had been inspired by a news item about a New York nanny who killed the two children in her care. The murders happened in 2012, but I remembered them in all their excruciating particulars: that the mother had been at a swimming lesson with a third sibling; that they came home and found the boy and the girl bleeding in the bathtub; that the nanny, who tried to slit her own throat, said she was upset at having been asked to take on cleaning duties; that the couple has since had two more kids. Once in a while, someone else’s misery penetrates the carapace of self-absorption under which you scuttle around and gets deep into you. Feeling somehow protective of the story, I was both beguiled and a little shocked by Slimani’s audacity in laying claim to it.

The Perfect Nanny, writes Rayyan Al Shawaf (San Antonio Express-News), “is like a gelid hand slowly closing itself around your heart—but never giving it the dreaded squeeze.”

Neel Mukherjee, A State of Freedom

Mukherjee’s “homage” to V.S. Naipaul’s In a Free State draws more applause.

Michael Schaub (NPR) writes, “[Mukherjee’s] latest book starts off benignly enough, but it doesn’t take long at all for him to twist the knife, letting the reader know that this isn’t going to be a saccharine, feel-good story. It’s a brutal novel that gets darker and darker, and it’s as breathtakingly beautiful as it is bleak.”

Thrity Umrigar (Boston Globe) notes:

Accustomed as we are to reading novels that follow a standard narrative arc, some readers may find it frustrating to read a book that labels itself a novel but lacks, as Mukherjee puts it, the “connective tissue” that ties disparate sections together. If most of the chapters share a theme it’s that most of the characters in “The State of Freedom’’ are migrants of one kind or the other, each trying to escape the inevitability of their marginalized existence and of being exiled in a no-mans land, which may or may not be better than what they have left behind.

“Mukherjee is a writer of abundant gifts,” writes David Takami (Seattle Times). “His descriptions are mostly spare and without artifice, but he can also deliver lustrous prose, as in this passage from the second chapter: ‘Despite the windscreen wipers semaphoring furiously back and forth, I could barely see anything in front and nothing very much at all through the streaking wall of water which was the passenger window. The whole world seemed to be deliquescing. After twenty minutes or so, the strafing abated somewhat although the rainfall continued; a seen-through-streams-of-liquid visibility was restored; the world became that of an Impressionist painting.’ He also writes with stunning detail about slums of India and the misery of entrenched poverty.”