The shortlists for this year’s CLMP Firecracker Awards include a glorious group of translated books on the fiction list, including Claudia Salazar’s Blood of the Dawn, translated from the Spanish by Elizabeth Bryer; Lucio Cardoso’s Chronicle of a Murdered House, translated from the Portuguese by Margaret Jull Costa & Robin Patterson; Ananda Devi’s Eve Out of Her Ruins, translated from the French by Jeffrey Zuckerman, and Guillermo Saccomanno’s Gesell Dome, translated from the Spanish by Andrea G. Labinger. The National Book Critics Circle’s “Beyond the Buzz” panel is coming up Thursday, June 1, at the Center for Fiction, blocks away from the swirl of the BEA. New York Times critics Nicole Lamy and Julian Lucas, the Washington Post’s nonfiction critic Carlos Lozada, and Bethanne Patrick and moderator Michele Filgate will talk about reviewing translated works and small-press gems.

Much sadness this week at the death of literary super nova Denis Johnson, the new Arundhati Roy novel is at the top of the week’s to-read list, Michael Crichton’s third posthumous book has its fans, Pulitzer Prize winning historian Tom Ricks contrasts Winston Churchill’s and George Orwell’s views of freedom, and in case you missed it, a newly translated biography of Polish Nobel laureate Czeslaw Milosz.

Denis Johnson, Jesus’ Son

Memories of reading Johnson’s work flood the internet. In tributes, major attention is given to the influence—the pure sense of discovery—evoked by his 1992 story collection Jesus’ Son, and especially the first short story in the collection, “Car Crash While Hitchhiking.” (Read it here in the Paris Review.) And there is another collection coming; (here’s the title story, “The Largesse of the Sea Maiden,” in The New Yorker).

Michiko Kakutani (New York Times) writes:

There is a fierce, ecstatic quality to Mr. Johnson’s strongest work that lends his characters and their stories an epic, almost mythic dimension, in the best American tradition of Melville and Whitman. In the interlinked stories in Jesus’ Son . . . , the narrator traverses the United States, moving through a grim, fluorescent-lit landscape of rundown bars and one-night cheap motels, and meeting a succession of misfits as alienated and desperate as himself—people who often seem like crazy, drug-addled relatives of the lost souls in Sherwood Anderson’s Winesburg, Ohio or strung-out exiles from a Lou Reed album.

Philip Gourevitch (The New Yorker) writes:

Johnson’s own fictional surrogate, the lowlife junky narrator of his most autobiographical and most popular book, Jesus’s Son, is named Fuckhead. “It’s a name that’s going to stick,” a fellow addict tells him. “‘Fuckhead’ is gonna ride you to your grave.” And it’s true. The name straddles the character like a slapstick fate. It tells you about Johnson, too: he’s harsh and he’s funny, and he’s always swinging between hardboiled and hallucinatory . . . Fuckhead is not someone you’re supposed to respond to as good or bad or even in between in any conventional sense. He is the American expression of what the Russians call a holy fool, a fleshing out of William Carlos Williams’s declamation, “The pure products of America go crazy.” He’s someone you have to respond to the way you respond to the deepest, weirdest, truest voices of rock and roll: you don’t want to be him, or even—if you’re at least halfway sane—to be with him; you just want to hear him tell it because when he does everything feels heightened.

“Take Jesus’ Son, which, 25 years after publication, remains his best-known work,” writes David L. Ulin (Los Angeles Times). “It is a book that sits at the very top of the pantheon, widely considered to be an American masterpiece. It is a book I’ve read so many times I feel as if I know it by heart. Here, we see the clearest expression of Johnson’s double vision, his gritty mysticism. Revolving around a recovering addict, it distills some piece of the author’s experience (‘I never quite became a hippie,’ he wrote, revealingly, in an essay about the Rainbow Gathering. ‘And I’ll never stop being a junkie’) into an act of expression so visionary, so stark in its clarity and its confusion, that it cannot help but become our own.”

Christian Lorentzen (Vulture) writes, “The stories in Jesus’ Son—I want to punch a wall whenever I hear them called ‘vignettes,’ though they don’t contradict the dictionary definition—have both an undeniably personal feel and the indelible power of myth. That power is in the book’s relentless succession of singular images. That the narrator and many of the characters spend the book drunk, high, cranked up, or burnt out is just the fabric of reality in their fictional world. The last thing they’d do is wonder whether they’re that kind of person, which isn’t to deny that the arc of the book bends toward recovery and redemption, of a sort.”

Christian Kiefer (San Francisco Chronicle) quotes from the ending of “Car-Crash While Hitchhiking” and adds:

“I would stand on Anton Chekhov’s table and proclaim that short story is the finest ever written, a perfectly balanced piece of fine sculpture made out of the detritus of a postlapsarian world. But that was, after all, the literary world of the man who wrote the story collection Jesus’ Son”—the landscape left to us after we got kicked out of Eden and had to make our way through the wreckage we had made. And yet there was often a sense in his writing that Johnson . . . could feel the grace and light shining through that wreckage and that he wanted to show us a way through to that grace and light.”

James Yeh (VICE) writes:

Denis Johnson probably saved my life more than once. I’ve read the stories in Jesus’ Son—that poetic druggie Bible—more than any other book. Over the years, I even kept several copies on hand so that I could pass them along to uninitiated friends (and have been pleasantly surprised to discover that I’m only one of many writers to do so). There was a time when I wanted to write the Asian American version of this book—or at least write with the Asian American version of its voice. I wanted to come up with those abrupt, jaw-dropping lines that would scramble your brain and heart and soul, and then hurl it all back at you with astonishing ease, verve, and humor.

He quotes same passage Kiefer does: “The scene that sums up Johnson, for me, is from his leadoff story to Jesus’ Son, ‘Car Crash While Hitchhiking.’”

This isn’t the first time “Car Crash” has been anointed best of the best. Nathan Englander (NPR) wrote in 2007: “Someone—I can’t remember who, and don’t remember when—gave me a Xeroxed copy of the first story [in the collection], ‘Car Crash While Hitchhiking.’” “If you look at the book, you’ll see the author’s name is absent from the margins, and not even the whole title of the story is there. So I read what I thought was called ‘Car Crash,’ and loved it and was moved by it. And then, in the way good reading makes you feel like your connection to it was fated, I soon ended up with a copy of the book in my hands. When I started it, I knew: This is that guy. And I read on and on, and thought, This guy is that good. I was living in Iowa City at the time, and this book, for my friends and me, became sort of a young writers’ bible.”

In 2012 Jeffrey Eugenides (The Paris Review) called it the “perfect short story.” He concludes his analysis: “Sobriety and sanity, precious as they are, do not compensate for the tragic senselessness of life. Redemption is glorious and it isn’t nearly enough. It saves only one person at a time, and the world is full of people. As if to emphasize this hard truth, the story concludes with a furious last line: ‘And you, you ridiculous people, you expect me to help you.’ Fuckhead isn’t Jesus. He’s Jesus’s son, which is a different thing entirely. He’s a person graced with an intuition of heaven who still lives in hell on earth.”

Arundhati Roy, The Ministry of Utmost Happiness

Two decades after publishing her first novel, The God of Small Things, which won the Man Booker award, and after many years of political activism, Roy returns to fiction. The buzz is just beginning.

A starred Kirkus Review calls the novel “worth the wait: a humane, engaged tale of love, politics, and no small amount of suffering.”

“From the novel’s beginning—‘She lived in the graveyard like a tree’—one is swept up in the story,” writes Daphne Beal (Vogue). “‘She’ is Anjum, born a hermaphrodite in Old Delhi, who, after being raised as a boy named Aftab, goes to live as a woman in a nearby home for hijras (the South Asian term for transgender women). Headstrong and magnetic, she becomes the spokesperson for the hijra community. But after barely surviving a Muslim pogrom in Gujarat, Anjum renounces everything to set up a solitary new life in a cemetery, where she builds a guesthouse among the gravestones that gradually becomes home to a colorful cast of characters.”

The starred Publishers’ Weekly review concludes:

Shifting fluidly between moods and time frames, Roy juxtaposes first-person and omniscient narration with “found” documents to weave her characters’ stories with India’s social and political tensions, particularly the violent retaliations to Kashmir’s long fight for self-rule. Sweeping, intricate, and sometimes densely topical, the novel can be a challenging read. Yet its complexity feels essential to Roy’s vision of a bewilderingly beautiful, contradictory, and broken world.

Michael Crichton, Dragon Teeth

Crichton’s third posthumous publication turns to the past.

John Wilwol (Philadelphia Inquirer) sets it up smoothly:

As though extracted from amber, a new story has been reanimated from the fossilized brain of Michael Crichton. Recently “discovered” in the late author’s archives (Crichton died in 2008), Dragon Teeth is a light historical novel that bears all the narrative traits of its techno-thriller ancestor Jurassic Park. It’s a fun romp through the Old West in search of dinosaur bones.

Steve Donoghue (Christian Science Monitor) has some fun with the believability of “three manuscripts by one of the world’s best-selling authors just sitting in his hope chest patiently awaiting discovery and periodic distribution to the world . . . ” But he doesn’t hold that against the book. “The novel is a lean, propulsively readable adventure story, filled with seamlessly-interwoven exposition and sharp dialogue. It’s easily the best thing with Michael Crichton’s name on it since 1999’s Timeline.” And he concludes: “These Crichton fossils being unearthed with such regularity are archeological gold.”

Jocelyn McClurg (USA Today) calls it a “fun, suspenseful, entertaining, well-told tale filled with plot twists, false leads and lurking danger in every cliffhanging chapter.”

Tom Ricks, Churchill and Orwell: The Fight for Freedom

Pulitzer Prize winning historian Ricks, who writes the Best Defense blog for Foreign Policy, returns to the 1940s and early 1950s, distilling the conflicts two enemies of totalitarianism who never met faced in an increasingly polarized world, with both having a “dominant priority, a commitment to human freedom,” that “gave them common cause.” “Orwell was right on the key question of the 20th and the 21st centuries,” Ricks tells the Seattle Times‘s Mary Ann Gwinn. “How do you protect the individual in the age of the all-intrusive state? Privacy is becoming a luxury in the 21st century. We are becoming accustomed to that, we are being data mined by the corporations and the state.”

Glenn C. Altschuler (San Francisco Chronicle) writes, “Ricks recounts the fight of two 20th century giants against the enemies of freedom. His book does not provide new information or fresh interpretations about his subjects, but it’s an elegantly written celebration of two men who faced an existential crisis to their way of life with moral courage—and demonstrated that an individual can make a difference.” Driving today’s “Orwell boom,” Altschuler adds, Ricks points to “the rise of surveillance states, the use of torture against terrorists, and the existence of ‘permanent wars.’”

“Ricks tracks his subjects without falling into the usual traps,” writes Matthew Price (Newsday). “He is neither sanctimonious about Orwell, nor overly reverential when discussing Churchill. As Ricks reminds us, the former wrote some minor novels and forgettable journalism before he found his stride in 1938 with Homage to Catalonia, his account of fighting in the Spanish Civil War. Churchill was bedeviled by his own issues.”

Richard Aldous (New York Times Book Review) concludes:

What comes across strongly in this highly enjoyable book is the fierce commitment of both Orwell and Churchill to critical thought. Neither followed the crowd. Each treated popularity and rejection with equal skepticism. Their unwavering independence, Ricks concludes, put them in “a long but direct line from Aristotle and Archimedes to Locke, Hume, Mill and Darwin, and from there through Orwell and Churchill to the ‘Letter from Birmingham City Jail.’ It is the agreement that objective reality exists, that people of good will can perceive it and that other people will change their views when presented with the facts of the matter.”

In other words, we don’t have to love Big Brother.

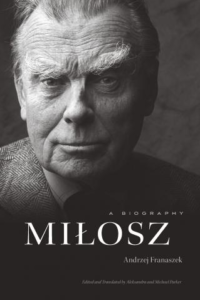

Andrzej Franaszek, Milosz: A Biography

The English translation of the 2011 biography of the 1980 Nobel laureate reminds us how he transcended erasure. Milosz’s work is eerily relevant today. “Perhaps a decade ago, it would have been easy to pass off The Captive Mind as a relic of the totalitarian 20th century,” Franaszek writes in the New York Times. “However, the last decade has demonstrated how the mechanisms of mind control Milosz exposed continue to be deployed throughout the globe.”

Robert Legvold (Foreign Affairs) writes, “In Milosz’s life, so well illustrated by Franaszek, poetry’s confrontation with history converged with the poet’s engagement, sometimes mystical, with humankind’s most basic values.”

Adam Kirsch (The New Yorker) calls Franaszek’s book “richly detailed, dramatic and melancholy.” ‘Ironically,” he notes, “as Franaszek writes, the war years were a time of flourishing for Milosz. Although, like all Poles under Nazi rule, he faced grave risks—on several occasions, he narrowly escaped German patrols and roundups—the arrival of the apocalypse he had long dreaded also set something free within him. He was active in the underground literary scene, compiling an anthology of wartime poetry and translating Shakespeare into Polish. His poetry acquired a new simplicity, directness, and pathos—several of his masterworks date from these years—and his stature among Polish readers grew. Still, the horrors that he witnessed and experienced permanently shaped his view of humanity and history.”

Troy Jollimore (Washington Post) concludes:

The poems generated by this profound engagement with the conundrums of human existence constitute a body of work like no other in contemporary poetry. Franaszek’s intelligent and comprehensive biography should be read in conjunction with Milosz’s New and Collected Poems: 1931-2001, reissued this month by Ecco. Together they provide a detailed and at times startling portrait, not only of one of the most fascinating and significant poets of the past hundred years, but of what it was like to be alive, curious, politically engaged and spiritually conflicted in the 20th century.

If you buy books linked on our site, Lit Hub may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.