In her New York Times review of A. M. Homes’ new short story collection, Days of Awe, Ramona Ausubel writes that Homes “skillfully circles and tugs at the question of what it means to live in flawed, fragile, hungry human bodies.” Over at the Boston Globe, William Pritchard considers the collected stories of the late, great Andre Dubus. David Canfield of Entertainment Weekly was both impressed and a little disappointed by Anne Tyler’s Clock Dance, calling the book “ultimately an argument for seeing an uneven story of high potential through to its conclusion.” We’ve also got Kate Kellaway on Deborah Levy’s “short, sensual, embattled memoir,” The Cost of Living, and Russian-American author Lara Vapnyar on Vesna Goldsworthy’s 1947-set “delightful literary tangle,” Monsieur Ka.

*

“A. M. Homes skillfully circles and tugs at the question of what it means to live in flawed, fragile, hungry human bodies. One character embeds rose thorns in her feet; several have very disordered eating habits; people die too young, go to war and hold in their cells and minds the memories of past trauma … One wants to read passages of a Homes story aloud because they are so fine … The absurd and the delicate occupy the same space. One story begins with a family going grocery shopping and ends with the father being nominated to run for president by fellow customers in the electronics aisle, while holding a baby his daughter found on a stack of towels. Whatever the tone, hanging over Days of Awe are questions about how we metabolize strangeness, danger, horror. Impossible things happen all the time. In each story the characters seem to be looking around at their lives and asking: Is this even real? Has the world always been so jagged? Days of Awe feels like the part of the day when the sun is about to go down and the light is brighter while the shadows are darker. Everything has a sharp edge, is strikingly beautiful and suddenly also a little menacing. As one character says, ‘In these times the only way to remain optimistic is to side with the darkness and then be pleasantly surprised.’ ”

–Ramona Ausubel on A. M. Homes’ Days of Awe (The New York Times Book Review)

*

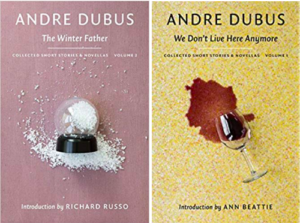

“Now the stories and novellas have been gathered in two volumes (a third is in the works) with appreciative introductions by Ann Beattie and Richard Russo. In her introduction to volume 1, which contains Dubus’s first collections, ‘Separate Flights’ and ‘Adultery and Other Choices,’ Beattie touches on perhaps the central impulse in Dubus’s fiction by noting how easy it is for writers to ‘corner their characters’ by making them submit to one or another humiliation, loss, failure. Although Dubus’s stories are filled with disasters—often involving marriages—in the best of his work ‘the story seems to have its own uncontainable energy and trajectory; it declares the inevitability of letting bad things happen’ … This ‘inevitable’ quality of life that the stories so often explore, is wholly connected to Dubus’s religious commitment as a Catholic, to taking human life seriously in the unhesitating belief that fiction is, or should be, about real people, usually in one or another kind of trouble. For Dubus this means the language of his stories is at the service of something outside itself. He is a ‘referential’ writer, rather than a post-modernist one whose concern is with the tricks and illusions language plays.”

–William H. Pritchard on Andres Dubus’ Collected Short Stories and Novellas (The Boston Globe)

*

“Clock Dance is a greatest-hits album in novel form. Anne Tyler’s latest book features most, if not all of her trademark themes and writerly quirks, and it moves briskly, but in absence throughout is a certain personality—a particularity … the novel toggles between playing to Tyler’s strengths and going through the motions of her relatively threadbare story beats … It’s that dreamy flow which, at her best, marks the author’s wisdom and vision as a chronicler of the human condition. But in Clock Dance it’s lacking in potency. Tyler seems anxious to keep things moving, more concerned with how character details and experiences fit together, puzzle-like, than really living in their humanity … Clock Dance is perhaps ultimately an argument for seeing an uneven story of high potential through to its conclusion. This is a book that improves significantly as it progresses … Rest assured, the dialogue is fun and snappy throughout; the final pages offer a warm and appropriately, exceedingly sentimental ending. Tyler still hits her marks.”

–David Canfield on Anne Tyler’s Clock Dance (Entertainment Weekly)

*

“…What is wonderful about this short, sensual, embattled memoir is that it is not only about the painful landmarks in her life—the end of a marriage, the death of a mother—it is about what it is to be alive … After her marriage breaks down—at a time when her career is ascending—Levy and her two young daughters move into a north London block of flats which she describes, in its stricken deficiency, with panache. She makes of the flat a story, with its big skies and its sterile corridor … She describes the bees that are her unexpected flatmates, her prospering strawberry plants, and the exotic oranges with cardamom that she and her daughters eat for breakfast. She writes entertainingly about her attempt, encouraged by a friend, at ‘living with colour’ – her yellow bedroom a garishly false move … This is a little book about a big subject. It is about how to ‘find a new way of living.’ ”

–Kate Kellaway on Deborah Levy’s The Cost of Living (The Observer)

*

“[A] subtle and deeply intelligent novel … Monsieur Ka refuses to be an homage to Anna Karenina. Instead, it tries to reimagine the characters of Tolstoy’s novel as real people who could have been its prototypes … The premise is simple and intensely engaging … [a] delightful literary tangle … Still, the richest and the most wonderful aspect of Monsieur Ka is not its literary gaming but rather its incessant attempts to make the reader question reality. All these fictional, factual, defictionalized, refictionalized layers allow Monsieur Ka to capture that elusive feeling every serious reader has experienced at some point: what if our lives are less real and not more real than the lives of literary characters? … This question stays with you long after you put down Monsieur Ka.”

–Lara Vapnyar on Vesna Goldsworthy’s Monsieur Ka (The Los Angeles Review of Books)