It’s that time of year again! No, not for anxiety dreams that you showed up in your underwear to the first day of school. Not for coming to terms with the fact that everything is going to taste like Pumpkin Spice™ for the next few months, either, though we’ll all have to do that emotional work. It’s #WiT month! Now, more is more isn’t typically my aesthetic, but when it comes to celebrating women* in translation, maximalism is where it’s at. Especially given the grim numbers Chad Post recently crunched over at the Three Percent blog. Not sure where to begin? How about where it all began, with Meytal Radzinski’s biblibio. And maybe this overview from Lit Hub, or this interview with Alta L. Price and Margaret Carson, who co-founded the WiT Tumblr. If you want to keep the party going all year round (and really, why wouldn’t you?), there are plenty of resources to check out. You can follow @Read_WIT, @biblibio, and @translatewomen to stay up to date, check out Rachel Daum’s lovely new Bookaccino, or read through these other WiT lists at your leisure. And don’t forget that you can be a resource, yourself, if the spirit moves you: make a recommendation, pass a dog-eared treasure on to a friend, or donate your latest fave to a local library. Here are a few of mine:

Tentacle by Rita Indiana

Translated from the Spanish by Achy Obejas

And Other Stories (January 2019)

Welcome, friends, to the book of AND. In Tentacle, Indiana—who is also a celebrated musician—draws on street culture, pop culture, Santería, world history, art history, and the tropes of speculative fiction to take on climate crisis, colonialism (in both its original and neo- varieties), racism, sexism, trans identities, class warfare, immigration, and… I’m pretty sure I’m leaving something out. The result is something chaotic and beautiful and smart as hell. The book’s opening distills many of these themes: in it, our protagonist Acilde looks up from cleaning the post-apocalyptic grime from her employer’s windows to see (through a security camera connected directly to her visual field) “one of the many Haitians who’ve crossed the border, fleeing from the quarantine declared on the other half of the island.” An automated process is activated and a lethal gas is released, the neighbors are automatically notified not to leave their homes for an appropriate lapse, and the man’s body is removed by an automated “collector” imported from China. We are in the future, but also not. Acilde’s story—she is plucked from the streets where she’s been hustling to save up for a wonder drug that offers a one-step gender transition and is brought to work in the home of an aging santera; she eventually gets the drug she needs to transition, at which point he is informed that he is the Chosen One and must travel back in time to prevent the man-made disasters that led to the destruction of the oceans—is interwoven with that of Argenis, a young man with artistic talent but no discipline who is plucked from his mother’s home to participate in a group project; he ends up living between centuries when a freak snorkeling accident (he is stung by anemones while trying to impress a married woman) leaves him with a consciousness split between the present and the early days of Spanish colonization. Obejas does a great job with the rapid-fire shifts between registers and dialects, and the whole thing just flows. It’s a lot to take in all at once, but just relax into it. You’re in for quite a ride.

Double take: Here’s the roundup, plus an interview with the author. Bonus: the music video for Indiana’s “El Castigador.” [Insert all emojis here.]

Mars by Asja Bakić

Translated from the Croatian by Jennifer Zoble

Feminist Press (March 2019)

Mars is the satisfyingly dystopian debut collection of short stories from Asja Bakić, a writer, translator, and co-founder of the feminist webzine Muff. Nested comfortably in the twilight zone, these stories push familiar scenarios (a cheating spouse, the serial killer next door) into the speculative realm and, in the process, push fiction in the direction of activism. They are also quite self-aware. Writing is at the center of many of these tales: in “Day Trip to Durmitor,” a woman dies and goes to a purgatory that she is expected to write her way out of, under the close scrutiny of two “secretaries” who offer her pointed critiques on her work. (This scenario hits uncomfortably close to home.) In “Asja 5.0,” one of several Asja clones is tasked with writing pornography that will help her patron (master) “be the first man to achieve an erection in god knows how many years.” This commentary on the pressure to (re)produce opens out onto broader social criticism: from the erotic stereotypes that Asja the clone dexterously employs to the assignation of jobs according to gender, it becomes clear that even in a world devoid of sex, sexism can still run rampant. The collection is also peppered with fantastic images and phrases rendered in an incisive deadpan by Jennifer Zoble: in the first story, death is described as “a European film,” while in another, the moon is “a nipple wanting to breastfeed my paranoia.”

Double takes: Andrea Blatz takes a look at the collection for Asymptote. Then there’s the starred review from PW and the roundup.

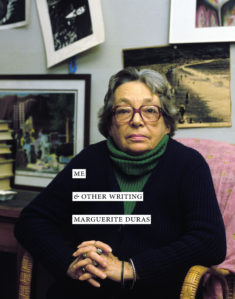

Me & Other Writing by Marguerite Duras

Translated from the French by Olivia Baes and Emma Ramadan

Dorothy Project (October 2019)

“I rarely read on beaches or in parks,” asserts Duras in “Reading on the Train,” a layered personal reflection on the engrossing, vertiginous, and sometimes disturbing practice of reading included in Me & Other Writing, a collection of the experimental writer and filmmaker’s nonfiction (if it could be classified as such, or at all). “It’s impossible,” she continues, “to read in two lights at the same time, that of the day and that of the book. One must read in electric light, the room in darkness, only the page illuminated.” The experience of reading these pieces is not dissimilar: the electric flow of Duras’s thought casts the rest of the world, briefly, into shadow. This is writing that demands, and provides, its own spotlight—not only through its incandescent intelligence (as in Duras’s reading of the violence enacted not by, but upon, Simone Deschamps in “Horror at Choisy-le-Roi”), but also through its refusal of linear exposition, the way it careens from one idea to another or dashes the reader’s expectation of authorly pronouncements by offering instead a lyrical image (Olivia Baes and Emma Ramadan reflect on the challenges of translating this opacity in an excellent note in the book’s final pages). Nowhere is this more evident than in “Summer 80,” a series of columns written weekly for the newspaper Libération that weave meditations on weather and the sea together with installments of fictional-allegorical narratives and the occasional interjection of world events. These pages emit a glow that can be disorienting at times, but which is well worth basking in.

Double take: Kirkus on this amalgam of “intense, poetic vulnerability and fervent political ideals.”

Doppelgänger by Daša Drndić

Translated from the Croatian by S.D. Curtis and Celia Hawkesworth

New Directions (September 2019)

Drndić, whose EEG was published in April to rave reviews, was never one to shy away from ugliness in her writing, and Doppelgänger—which she affectionately called “my ugly little book”—is no exception. In the first of the two texts that make up the volume (and which intersect at a point I won’t mention here), “Artur and Isabella,” two elderly, isolated individuals in “an ugly small town” meet on New Year’s Eve and spend a few hours together while, unbeknownst to them, their homes are searched by the secret police. Artur shares a few pertinent facts about his life—his former Navy post; his bedridden wife, now deceased—and Isabella in turn shares a few of her favorite chocolates. She does not mention the 36 garden gnomes that watch over her apartment, one for each member of her family killed in concentration camps during the Holocaust They sit on a stone staircase facing the promenade. They have sex. (“The diapers are—thank god—dry. Both hers and his are clean and dry.”) They each return home, as empty as before. The volume’s second, longer, narrative centers on a middle-aged man named Printz but called “Pupi,” who has moved back home after two failed marriages and is dominated in turns by his ailing opera diva mother and his brother’s wife, who is her spitting image; by his brother, who makes off with everything worth anything in the household while maintaining a veneer of respectability; and by his father, who dashes Printz’s hopes of becoming a sculptor when he demands that he take up the family line of chemistry and espionage. Printz slips further and further into isolation and despair, his only anchor the rhinos at the run-down city zoo. His identification with these animals, the way he processes his own experience through what he knows of their species, culminates in the book’s brutal final scene. Just as these stories reflect back on one another, doubles are formed by the horrors that double the characters over; likewise, in both, an absolute act of refusal is the only option each has to take back control of their bodies from an oppressive and omnipresent State. This is by no means an easy book, but it is one of the most breathtaking I’ve read in a long time.

Double take: The late Eileen Battersby for the Financial Times. Bonus: Lucy Popescu’s piece on the author for The White Review.

* Anyone who identifies as such, as well as non-binary and intersex individuals.

Previous entries in this series