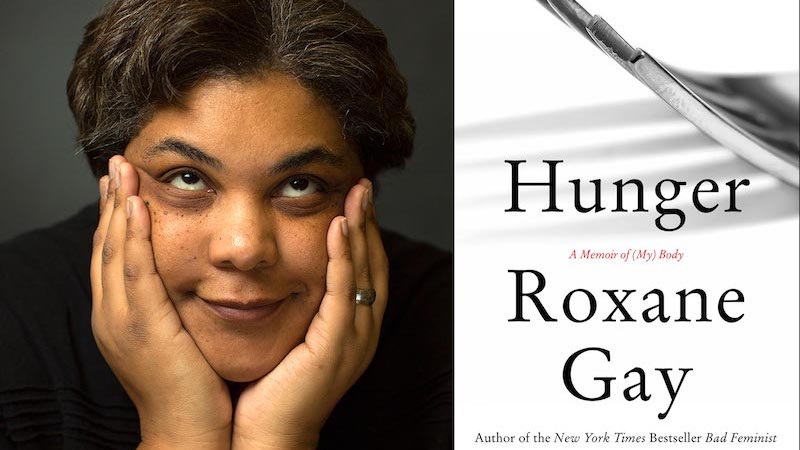

In the 30 books in 30 days series leading up to the March 15 announcement of the 2017 National Book Critics Circle award winners, NBCC board members review the thirty finalists. Today, NBCC board member and autobiography committee chairman Laurie Hertzel offers an appreciation of autobiography finalist Roxane Gay’s Hunger: A Memoir of (My) Body (Harper)

Hunger comes in many forms. We hunger for food, for love, for romance, for safety. In her fierce and devastating memoir, Hunger: A Memoir of (My) Body, essayist Roxane Gay explores all of these desires, desires that have seized control of her body and deeply affected her life.

“What you need to know is that my life is split in two,” she writes, “cleaved not so neatly. There is the before and the after. Before I gained weight. After I gained weight. Before I was raped. After I was raped.”

Gay was still a child when this terrible crime took place, just 12 years old. “He was a good boy from a good family living in a good neighborhood, but he hurt me in the worst ways.” He lured her to an old hunting cabin in the woods where several of his friends waited, and “where no one but those boys could hear me scream.”

Just before the gang rape, as the boys mocked her and laughed, she felt “smaller and smaller,” she writes. It is no surprise that after the rape she grew as big as she could possibly grow.

She ate her body into a fortress—at its largest, well over 500 pounds.

Hunger is about both the profound effects of this childhood violence, and about the profound effects of growing to such a size. She writes about what it physically feels like to be large, and she writes about the way the world views her. She examines diets and clothes and furniture and sex and popular culture and the looks that people give her. “This is an unspoken humiliation, a lot of the time,” she writes. “People have eyes. They can plainly see that a given chair might be too small, but they say nothing as they watch me try to squeeze myself into a seat.”

This book is a startling, humbling read. The lives people have led: We have no idea. She knows that we judge. She knows that we have no right to judge.

Gay cuts herself no slack. She is as hard on herself as she is on society, on the rapist. “I reserve my most elaborate delusions and disappointments for myself,” she says, and sometimes you want to tell her, forgive yourself. You did nothing wrong.

Gay writes in measured, sometimes terse, tones. Her sentences are short, as are her chapters—some are just one paragraph, or just one page. But oh, how powerful those paragraphs are. They course with deep anger and palpable pain. That terseness holds back a mountain of feelings.

And everything circles back, again and again, to that hunting cabin in the woods.

Toward the end of the book, in a breathtaking chapter, Gay writes of tracking the boy down online, years later. Finding him “became a minor obsession,” she says. And when she does find him, she had no doubt (“There are some faces you don’t forget”) but sat for hours staring at his face on her computer screen. “It nauseates me. I can smell him.” She imagines staking him out but instead calls him. She does not speak. She waits. She listens. She remembers, and she imagines.

“Writing this book is the most difficult thing I’ve ever done,” she says in the very last chapter, one last bit of brutal honesty in a book filled with honesty on every page.

Laurie Hertzel is the senior editor for books at the Minneapolis Star Tribune and a board member of the NBCC. Her memoir, News to Me: Adventures of an Accidental Journalist, won Minnesota Book Award’s readers’ choice award. She teaches memoir writing at the Loft Literary Center in Minneapolis.

If you buy books linked on our site, Lit Hub may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.