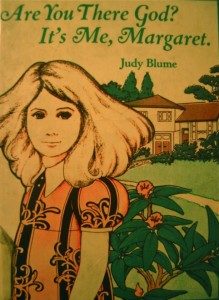

Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret (1970)

“The comical longings of little girls who want to be big girls—exercising to the chant of ‘We must—we must—increase our bust!’—and the wistful longing of Margaret, who talks comfortably to God, for a religion, come together as her anxiety to be normal, which is natural enough in sixth grade. And if that’s what we want to tell kids, this is a fresh, unclinical case in point: Mrs. Blume has an easy way with words and some choice ones when the occasion arises. But there’s danger in the preoccupation with the physical signs of puberty—with growing into a Playboy centerfold, the goal here, though the one girl in the class who’s on her way rues it; and with menstruating sooner rather than later—calming Margaret, her mother says she was a late one, but the happy ending is the first drop of blood: the effect is to confirm common anxieties instead of allaying them. (And countertrends notwithstanding, much is made of that first bra, that first dab of lipstick.) More promising is Margaret’s pursuit of religion: to decide for herself (earlier than her ‘liberal’ parents intended), she goes to temple with a grandmother, to church with a friend; but neither makes any sense to her—’Twelve is very late to learn.’ Fortunately, after a disillusioning sectarian dispute, she resumes talking to God. . . to thank him for that telltale sign of womanhood. Which raises the last question: of a satirical stance in lieu of a perspective.”

–Kirkus Reviews, October 1, 1970

*

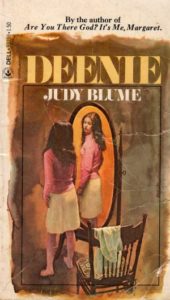

Deenie (1973)

“As the doctor marks her plaster cast with a felt pen to show the braceman where he should put the straps, he might as well be marking the spot in the narrative where Deenie must also fit herself into a new role—finding out what’s beneath the pretty face that was masking whatever was underneath … how wonderful that this is not a simple comeuppance story, since it would have been so easy for Blume to make this a tale of the conceited beauty who gets brought low by her own flaws. (ALSO: BLUME IS A GENIUS.) Deenie’s not conceited, she’s just passive—a very minor flaw that, as Blume knows, in the long run can have far more dire results than excessive self-regard (which, unfortunately, kinda works in one’s favor). Ironically, it’s Deenie’s brace that frees her from the invisible brace her mother was setting up for her, an adolescence locked into a role that would have derailed her growth as a real person. The plastic, with its collar and straps, chafes, but it’s a minor cage—and, unlike the cage her mother had in mind, one Deenie can emerge from with her standing intact.”

–Lizzie Skurnick, Jezebel, June 13, 2008

*

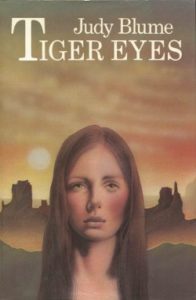

Tiger Eyes (1981)

“Blume’s portrayal of these emotions and characters is never overdrawn or sentimental; she allows the reader to share her characters’ needs and thoughts, fears and feelings. At last, Davey—’Tiger Eyes’—realizes that overcoming fear is only half her task. In a letter to Wolf she writes: ‘I don’t want to go through life afraid. But I don’t want to wind up like my father, either. Sometimes I think about dying and it scares me, because it’s so permanent.’

…

In Tiger Eyes, Judy Blume adopts a more serious tone than the humorous approach her fans know well. But she retains her ability to create believable characters and her shrewdness in dealing with the knotty philosophical questions that preoccupy young readers. In exploring the question of how to live in our increasingly violent society, in fear or with courage and faith, Blume has written her best novel.”

-Martha Rasmussen, The Des Moines Register, November 8, 1981