Humans have a tendency to think things have always been the way they currently are. Few would believe that as recently as the 1920s, most Americans preserved their perishables in insulated boxes, chilled by blocks of ice cut from northern lakes and rivers—and distributed door-to-door by none other than the iceman. Fewer still would believe that when Caesar rode into the Sahara Desert to conquer North Africa in 47 B.C., the region was well-watered and thick with forests and green savannas.

It is hard enough to conceive of a time before cell phones and the Internet—when humans de-limbed and deep fat fried one another because of disparate views about stars or gods or who should be king—much less to think there was a time when there were no humans at all, and the planet was covered from pole-to-pole in ice three miles thick. But that’s the way it was, and very likely, the way it will be again someday.

Much of humanity’s awkward history on this planet has been guided by a single molecule—H20—that has given and taken life on Earth since Day One. Just as the manipulation of Mesopotamia’s waterways gave rise to the world’s first kingdoms, mismanagement of water resources finished off several of the great early civilizations in the Americas. On a planetary scale, the balance of water—how much is frozen on Earth’s crust, how much circulates in the clouds, how much falls as rain, snow, sleet and hail—affects everything from the frequency of ice ages to droughts to sea level rise to drinking water and food availability. (Drought and failed crops resulting from the Little Ice Age of the 1600s, that cooled Europe by 2.5 degrees Fahrenheit, shrank the average height of Europeans by an inch and sparked a century of violent warfare.)

A few books about water stand out not only as harbingers of troubles to come, but terrific adventure tales as well. You see, to write about water you have to follow it. And to follow it, you have to get on it.

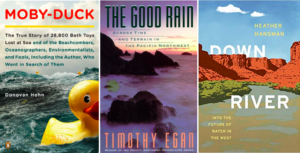

There is no better treatise on the sad state of the seven seas than Donovan Hohn’s epic Moby-Duck (Viking, 2011). Hohn’s exhaustive reporting on plastics in the ocean takes him on an Ishmael-esque journey around the world—tracking beachcombers, activists, freighter captains, self-made oceanographers and 28,800 rubber duckies that fell off of a container ship in 1992.

Hohn’s research is revelatory: rogue waves are coming for us; invisible ocean currents make the world go ‘round; disintegrated plastic has been absorbed by, well, everything; aquatic activism might be as futile as it appears. More importantly, Hohn does what few writers have achieved when documenting existential environmental tragedies: he connects the piecemeal destruction of our world directly to the cause—consumers.

Hohn inspects everything from the marketing and business practices of the toy industry to “the bestiary of childhood” to how the hardships of World War II made the victors hungry for mass quantities of cheap consumer goods—and how China’s authoritarian economy was the perfect wellspring from which rivers of plastic would one-day flow. Not even a shabby hotel on Hawaii’s Big Island escape Hohn’s sharp eye: “My room is monastically spare—no television, no telephone, no clock, only a tattered orange paperback copy of The Teaching of Buddha, left out, like the Gideon Bible, as if to entice converts, on the round table between the two saggy queen-size beds.”

As someone who has covered the metamorphic consequences of climate change for a decade, what I find so remarkable about Hohn’s book is not simply the reporting, but the way that Moby-Duck teaches us about why we pollute—a lesson vastly more valuable and necessary than how much we have contaminated the planet or how we should clean it up. In the end, responsibility for this calamity does not lie with shipping lines, Chinese factories, retailers or government regulators. It rests with the consumers of shiny, instantly gratifying, highly toxic things. Hohn’s enduring lesson: Until we alter our own nature, Mother Nature will continue to feel the brunt of our nescience.

Timothy Egan’s classic The Good Rain (Vintage, 1991) is another whirlwind tale of oceans, rivers, bizarre characters and environmental catastrophes. The veteran New York Times reporter and columnist spins his story as he chases water—“the master architect of the Northwest”—from the mouth of the Columbia River to the glaciated peaks of the North Cascades. Egan’s observations of over-tapped water supplies, hydroelectric dams, melting glaciers and crowded cites are fascinating, considering that they were written in 1990, just three years after the first Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change convened for the first time.

Egan begins his journey in the wettest corner of the Lower 48, the Olympic Peninsula—a land so overgrown with life that the “weight of living matter” there surpasses any region in the world. Lewis and Clark spent four miserable months here at the end of their western odyssey. After missing the mouth of the Columbia three times, Captain James Cook feasted nearby on human arms, a delicacy of the local Vancouver Island tribe. Lastly, gentleman adventurer and author Theodore Winthrop, a Yale graduate who explored the Northwest in the 1850s and wrote a bestselling book about the region, passed through the area as well—and stands in as Egan’s muse. “The moisture is predatory in this part of the world,” Egan writes. “And no element, be it stone or wood or tin or steel, lasts very long without losing some part of its composition to the nag of precipitation.”

As Egan moves upstream, he finds logging camps founded by John Jacob Astor (Astoria), the longest wilderness beach in America, and the “sawblade skyline of the North Cascades.” Beat poets Gary Snyder, Philip Whalen and Jack Kerouac once retreated to the range to work as fire lookouts and write. Legendary climber Fred Beckey blazed routes up the most precipitous peaks of the range, naming them with various sexual innuendos and wine varietals. “These mountains rise from the sea, holding the weight of every storm that blows east off the ocean, delivering an annual dump of 650 inches of snow on the summit barriers,” Egan writes.

One of the most rugged and remote mountain ranges in the world, and one of the last regions in the U.S. to be mapped, the North Cascades once held half of the glacial ice in the Lower 48. All of which feeds “The Great River of the West,” as Thomas Jefferson called it. “The only river to smash through the Cascades, the Columbia carved an eighty-five-mile gorge through the basalt spine of a mountain range with little fat. Snowmelt from the Cascades, the Rockies, the Selkirks, the Monashees, the Bitterroots, and every ounce of pine sweat and heather dew west of the Continental Divide from lower British Columbia to parts of Utah, Wyoming, Montana, Idaho, Nevada, Oregon and Washington muscle their way into the Columbia.”

Heather Hansman’s new book Downriver (University of Chicago Press, 2019) picks up the story of water in the U.S. West in 2019—a region that has been desertifying for decades and will likely continue to do so in the age of climate change. Hansman follows the Green River 730 miles from its headwaters to its confluence with the embattled Colorado River. “The water in the Green, and in the rest of the Colorado River system, is over-allocated, and has been since the 1920s, when its estimated flow was divided up between the seven states along the rivers,” Hansman writes.

The stat is the first in a flurry of data, regulations and legislation that Hansman provides to paint a picture of the ridiculously complex web of water rights in the West. The basic idea: The region is running out of water and regulations aren’t going to change that. “Drought has wracked most of the western half of the U.S. since the beginning of the twenty-first century, draining reservoirs and depleting aquifers,” Hansman writes. “Water is mired in the future of the climate, it’s tied to the physical, political, and economic divide between urban areas and rural ones, and it’s crucial to the debate about future energy sources. And more than anything, it’s indispensable. More than oil. More than food.”

In one chapter, “Water Change is Climate Change,” Hansman pulls back the curtain on the future of the Colorado River: “…instream flows in the whole Colorado River Basin could be cut in half by the end of the century because of climate change.” Translation: 40 million people and a third of the cities in Southern California that depend on the Colorado for their drinking water are about to see it cut in half.

Downriver does an excellent job painting a picture of the myriad problems water rights present in the U.S., but it doesn’t stand up to Hohn’s or Egan’s personal tales (little does). To hit that level of discovery, and narrative transcendence, you have to slow down, obsess over the little things, and bring all of the big, scary news about water and life down to our level. “Here, then, is one of the meanings of the duck,” Hohn writes in Moby Duck. “It represents this vision of childhood—the hygienic childhood, the safe childhood, the brightly colored childhood in which everything, even bathtub articles, have been designed to please the childish mind, much as the golden fruit in that most famous origin myth of paradise ‘was pleasant to the eyes’ of childish Eve.”