Colson Whitehead’s Crook Manifesto, Patrick deWitt’s The Librarianist, Kate Zambreno’s The Light Room, and Silvia Moreno-Garcia’s Silver Nitrate all feature among the Best Reviewed Books of the Month.

1. Crook Manifesto by Colson Whitehead

(Doubleday)

13 Rave • 8 Positive • 4 Mixed • 1 Pan

Read an interview with Colson Whitehead here

“Both deceptively substantive and sneakily funny, a wise journey through Harlem days and nights as lived by Ray Carney, a conscientious furniture salesman and family man who happens to run a little crooked … Whitehead has always had a sharp instinct for the workings of culture … Whitehead’s New York of the ‘70s is a fully realized universe down to the most meticulous details, from the constant sirens and bodega drug fronts to a sweltering, abandoned biscuit factory … A…reminder, as if we still needed one, that crime fiction can be great literature. These books are as resonant and finely observed as anything Whitehead has written.”

–Chris Vognar (The Los Angeles Times)

2. After the Funeral by Tessa Hadley

(Knopf)

14 Rave • 6 Positive

Read an interview with Tessa Hadley here

“This new collection is a great introduction to her work and for those of us already familiar with Hadley, it’s a great addition. Throughout the collection, Hadley spins out character studies of (mostly) women at odds with themselves, their partners, their families, or life in general … Hadley does a wonderful job of weaving past and present together as the sisters are forced to confront their memories and relationships. And, of course, there are those moments of shining prose … Rife with deft and often beautiful prose, and astute but compassionate characterization, this is a wonderful collection.”

–Yvonne C. Garrett (The Brooklyn Rail)

3. Nothing Special by Nicole Flattery

(Bloomsbury)

4 Rave • 10 Positive • 3 Mixed

Read an excerpt from Nothing Special here

“Exquisitely disorienting … The book is driven by a kind of respiratory imagining, a panting projection that sustains both Mae and the story. She subjects her world and the people who populate it to a ravenous metamorphosing … Some might find the plot’s relentless dissociation a decelerator, but I found it brave and effective: Flattery remains so loyal to the physics of her character’s struggles, to the struggle of storytelling itself, that she is willing to risk allowing the less committed reader to wander off. The point of this novel is not illumination; it’s almost an accident that we get to know Mae at all. Instead the novel captures, in gorgeous prose, the happy and unhappy coincidences that allow us to fall into knowing, those unexpected snags that trip us into ourselves … A revelation that is also distinctly anti-revelation, by a writer whose withholding is as vivid as her bestowing, who shows a story for what it is—something real, something fabricated, something to hide in and from, something special, something so utterly unremarkable it’s the only thing that matters.”

–Alice Carrière (The New York Times Book Review)

4. The Librarianist by Patrick deWitt

(Ecco)

5 Rave • 7 Positive • 5 Mixed

Read an excerpt from The Librarianist here

“I think each Patrick deWitt novel is going to be the one that helps everyone fall in love with his writing, but The Librarianist could finally do it … DeWitt’s dialogue moves with the speed and precision of great conversation and its jokes sneak up on you, more like a wisp of wind on your cheek than someone tapping you on the shoulder to tell you something funny … Bright and entertaining from beginning to end.”

–Chris Hewitt (The Star Tribune)

5. Silver Nitrate by Silvia Moreno-Garcia

(Del Rey)

6 Rave • 4 Positive • 1 Mixed

“True to her method, she succeeds here by knowing when to follow the rules of genre storytelling and when to turn them upside down … Several times in Silver Nitrate, a spirit commands, ‘Follow me into the night.’ While the better part of us hopes Montserrat and her compatriots will refuse, there is simply no resisting the dark spells cast by Moreno-Garcia’s characters—nor those so expertly cast over readers by the author herself.”

–Paula L. Woods (The Los Angeles Times)

**

1. Thunderclap: A Memoir of Art and Life & Sudden Death by Laura Cumming

(Scribner)

9 Rave

“Genre-defying … Cumming suggests that we recall the past through pictures … Cumming clearly loves these paintings, and by weaving together vivid evocations of ones that particularly move her with brief biographies of the men and women who painted them, she invites us to share that love … Like all good elegists, Cumming, too, brings the dead to life in the very act of mourning them.”

–Ruth Bernard Yeazell (The New York Times Book Review)

2. Into the Bright Sunshine: Young Hubert Humphrey and the Fight for Civil Rights by Samuel G. Freedman

(Oxford University Press)

5 Rave • 3 Positive

“Riveting … Freedman tells a surprising and rare history of Black and Jewish Americans fighting against racism and antisemitism, often side by side, in a Northern city before the civil rights era. His brilliant profiles of these local heroes are gripping and, in many ways, the spine of the book … Freedman gives us a dramatic retelling of the backdoor dealings at the convention over the language of a civil rights plank.”

–Khalil Gibran Muhammad (The New York Times Book Review)

3. The Light Room by Kate Zambreno

(Riverhead)

2 Rave • 7 Postive

Read an interview with Kate Zambreno here

“Zambreno’s writing is sharpest, most emotionally alive, when it drills into that interior landscape … Woven into these moments are ruminations on natural history, education and the work of other writers and artists … Readers looking for sturdier insights into what the virus has meant for human history are unlikely to discover them here. But there is comfort and intimacy to be found in the nest Zambreno builds, with lint and marbles and straw, the objects that matter in her tiny universe. Its achievement is as a sustained narrative of noticing.”

–Eleanor Henderson (The New York Times Book Review)

4. Owner of a Lonely Heart by Beth Nguyen

(Scribner)

3 Rave • 5 Positive

Listen to an interview with Beth Nguyen here

“Nguyen is a confident and reliable protagonist even when running up against painful memories, providing readers with enough distance as to almost be objective … Nguyen has made a journey of facing her origins and contending with the limitations of American narratives, and we are lucky to be invited along the way.”

–Mai Tran (The Brooklyn Rain)

5. Tabula Rasa by John McPhee

(Farrar, Straus and Giroux)

5 Rave • 1 Positive

“A charming, breezy collection of reminiscences about projects that didn’t make it, ideas that never got fully baked, research never written up, either because the subject died or because McPhee, who was born in 1931, lost interest along the way … Few of the subjects discussed in Tabula Rasa call out for the longform treatment; McPhee’s instincts (and editors) steered him well. But there are still pleasures to be had in these 50 short chapters. Minor league McPhee is still major league writing. It’s not faint praise to say he is still more pleasingly consistent than any other writer working. There is never a dud metaphor, never a cliché … He still has stories to tell. Maybe they’re just not the ones he had the good sense to let go.”

–Mark Oppenheimer (The Washington Post)

Our quintet of quality reviews this week includes Álvaro Enrigue on Cristina Rivera Garza’s Liliana’s Invincible Summer, Christian Lorentzen on Henry Bean’s The Nenoquich, Dana Schwartz on Kate Flannery’s Strip Tees, Nicole Flattery on Lynne Tillman’s Mothercare, and Hamilton Cain on Richard Russo’s Somebody’s Fool.

“Rivera Garza has an iron loyalty to her working method, whose goal is to find what is significant for the present in ignored episodes from the past. As the political situation of Mexico become more and more asphyxiating for a population exhausted by the government’s failure to control the violence of organized crime, her narrative focus changed: her books became more defiantly political and more personal … The femicide of Liliana Rivera Garza went almost unnoticed by the press when it happened—July 1990—but, thanks to this book, has become emblematic of the failure of Mexican justice to prosecute crimes in which the victim is a woman … In the novel Cristina Rivera Garza describes the days she herself spent bouncing between precincts and judicial records buildings in search of the closed file on her sister’s murder. Over this melancholic narration, in which Mexico City is lyrically portraited as a beautiful but devastated landscape, Rivera Garza constructs her story as a monument, pulling information from all sorts of sources … Liliana’s Invincible Summer is not a journalistic book about the crime that led to the author’s sister’s death, nor is it a literary evocation of a life and the grief its vanishing produced, but something much more powerful that happens at the crossroads of narration and archive. A story, and all the data that needs to be known to be devastated by it. Catharsis—a sentiment strong enough to produce inner change—for a time when reality is amplified by the omnipresence of information.”

–Álvaro Enrigue on Cristina Rivera Garza’s Liliana’s Invincible Summer (BookPost)

“Cynicism, laziness, anger, misplaced righteousness, vacillation between vanity and self-loathing: Such are the qualities of the superfluous men we’ve encountered in novels for centuries. Existing somehow outside the structures of family and regular employment, these prodigal sons have too much time on their hands — time to spend thinking, ranting, writing or intoxicating themselves. In the novels they narrate, they are suspended between delusions of grandeur and the dread of hitting rock bottom. The books consider the possibilities of freedom and failure that arise from the times and places that inspired them, even if their protagonists are bound for the usual destination: bourgeois assimilation. They usually tell us something about their moment’s sexual mores because more often than not their rakish heroes spend much of their idle days on romantic intrigues. One such case is Harold Raab, the narrator of Henry Bean’s first and only novel … Something else that hangs over The Nenoquich like an exhausted love affair is the 1960s. The book is told from a state of aftermath … Bean writes erotic scenes with a frankness and gusto uncommon in literary fiction today … Like his characters, Bean was not long for Berkeley. ‘All my friends,’ Harold says, ‘are moving from the flatlands up to the hills, and eventually they topple over the ridge into Los Angeles or New York.’ The Nenoquich now returns as a chronicle of sex and death in youth and a portrait of the baby boom generation at a turning point—between political radicalism and the path of temptation, fulfillment and disappointment that came to define it.”

–Christian Lorentzen on Henry Bean’s The Nenoquich (The New York Times Book Review)

“Though Strip Tees is a memoir, its story begins like a classic Hollywood noir. Kate Flannery is down on her luck, out of work and nearly out of money, drinking alone at a bar in Los Angeles. Suddenly, out of nowhere, a gorgeous stranger beckons with a mysterious job offer. Soon, Flannery is engrossed in a shadowy world of sex and money, while contemplating moral compromises that threaten her very soul. The job offer, to be clear, was at a clothing store … Strip Tees goes down as easy as a rum and Diet Coke, breezily written and punctuated at its intermission by a few pages of glossy photos. Reading it reminded me of being in middle school and sitting cross-legged on the couch with my neighbor, a freckled all-American blonde a few years older than I who had just gotten a job working at Abercrombie & Fitch at the mall … Though Flannery is clear-eyed about the exploitation and pettiness of American Apparel under Charney—and the cruelty of a culture in which a woman’s best method for career advancement was turning him on—she avoids the pitfalls of easy dogmatism, weaving in the sneaking suggestion that perhaps every company is just as exploitative, if not quite so nakedly … merely dismissing Charney as an aberrant offender—the one bad apple, good riddance—is a too-tidy conclusion for why these messy, glittering worlds continue to captivate us. Flannery seems unwilling to turn her memoir into a tidy morality tale. Good. Perhaps the book’s most important moral exists in the telling of the story itself. Here, Flannery says, gather round and let me tell you what happened to me. I went through this, she says, so maybe you won’t have to.”

–Dana Schwartz on Kate Flannery’s Strip Tees: A Memoir of Millennial Los Angeles (The Washington Post)

“Lynne Tillman doesn’t believe in redemption. ‘Contemporary novels,’ she complained in 2001, ‘have become a repository for salvation; characters–and consequentially readers–are supposed to be saved at the end.’ Tillman has always avoided sentimentality. ‘Detachment would keep her fresh, it was a kind of freedom,’ the narrator says in Haunted Houses (1987), her first novel. But if you don’t believe in salvation, how do you feel about death? That’s the question Tillman asks in her most recent and most autobiographical book … Tillman is especially interested in her mother’s ‘helpers’, a number of whom are mentioned throughout the book. She’s concerned with the ethical question of who is doing the helping, since the majority of carers in the US are people of colour. She knows that she and her sisters have hired poorly paid and possibly undocumented women to help their mother. The choice, as she sees it, is her life or theirs…It’s in the descriptions of these carers—women who are both inside and outside the family—that Mothercare begins to resemble a typical Tillman novel. She demonstrates the same talent for compression, the same affection for bizarre behavior, that characterized earlier books … Perhaps because Tillman isn’t a needy writer—she doesn’t perform self-satisfied tricks, she doesn’t concede, her bursts of humor are surreal and self-contained, close to private jokes—Mothercare is a peculiarly un-American book, free of self-actualization or therapy speak. It’s an egoless memoir, a messy house. ‘Redemption,’ Tillman tells us, ‘is an American disease’ … Mothercare shows us the end. Reading it, you feel Tillman’s clammy grip on your wrist reminding you not to waste time. She offers a writer’s prescription: examine the world closely, and as only you can.”

–Nicole Flattery on Lynne Tillman’s Mothercare: On Obligation, Love, Death, and Ambivalence (London Review of Books)

“Russo’s characters are caught in limbo. Scratch their psychic scabs—which he does, again and again—and rage and sorrow spill out … There are scattered potholes in Russo’s plot, which he patches with back story; we need not consult the other Fool volumes. Some chapters feel burdened with detail, and a few flashbacks are confusing, with scenes planted uneasily within scenes. And yet these characters’ interlocking fates move confidently toward resolution … In Russo’s hands these intentions—and the expectations and forgiveness of others—are fine brushes and a palette. He paints a shining fresco of a working-class community, warts and all, a 30-year project come to fruition in this last, best book. What happens in North Bath doesn’t stay in North Bath. And the trilogy’s true protagonist still inspires loved ones from beyond the grave. When Rub finds himself in a pickle, he summons Sully’s voice—and the dead man answers: ‘Untroubled by self-doubt, unafraid to be wrong and immune to after-the-fact criticism, Sully was Rub’s polar opposite and exactly what his present circumstances called for.'”

–Hamilton Cain on Richard Russo’s Somebody’s Fool (The New York Times Book Review)

Colson Whitehead’s Crook Manifesto, Silvia Moreno-Garcia’s Silver Nitrate, and Samuel G. Freedman’s Into the Bright Sunshine all feature among the Best Reviewed Books of the Week.

1. Crook Manifesto by Colson Whitehead

(Doubleday)

10 Rave • 7 Positive • 3 Mixed • 1 Pan

Read an interview with Colson Whitehead here

“Both deceptively substantive and sneakily funny, a wise journey through Harlem days and nights as lived by Ray Carney, a conscientious furniture salesman and family man who happens to run a little crooked … Whitehead has always had a sharp instinct for the workings of culture … Whitehead’s New York of the ‘70s is a fully realized universe down to the most meticulous details, from the constant sirens and bodega drug fronts to a sweltering, abandoned biscuit factory … A…reminder, as if we still needed one, that crime fiction can be great literature. These books are as resonant and finely observed as anything Whitehead has written.”

–Chris Vognar (The Los Angeles Times)

2. Silver Nitrate by Silvia Moreno-Garcia

(Del Rey)

5 Rave • 3 Positive • 1 Mixed

“True to her method, she succeeds here by knowing when to follow the rules of genre storytelling and when to turn them upside down … Several times in Silver Nitrate, a spirit commands, ‘Follow me into the night.’ While the better part of us hopes Montserrat and her compatriots will refuse, there is simply no resisting the dark spells cast by Moreno-Garcia’s characters—nor those so expertly cast over readers by the author herself.”

–Paula L. Woods (The Los Angeles Times)

3. Small Worlds by Caleb Azumah Nelson

(Grove)

5 Rave • 2 Positive • 2 Mixed

Read an excerpt from Small Worlds here

“Turning pain into a blissful art form is nothing new for black creators, many of whom are namechecked in this culturally open novel. But Azumah Nelson is something new: an unashamedly clever, spiritual, angry, loving voice in fiction, just when we need it most. Small Worlds is a book for everyone. Sure, unless you are a London teenager or live with one, you’ll probably miss the resonance of some words and phrases—but no matter. No one could fail to feel the message, of always striving for emotional honesty and hope, that is at the heart of this uplifting symphony of a summer read.”

–Melissa Katsoulis (The Times)

**

1. Into the Bright Sunshine: Young Hubert Humphrey and the Fight for Civil Rights by Samuel G. Freedman

(Oxford University Press)

5 Rave • 3 Positive

“Riveting … Freedman tells a surprising and rare history of Black and Jewish Americans fighting against racism and antisemitism, often side by side, in a Northern city before the civil rights era. His brilliant profiles of these local heroes are gripping and, in many ways, the spine of the book … Freedman gives us a dramatic retelling of the backdoor dealings at the convention over the language of a civil rights plank.”

–Khalil Gibran Muhammad (The New York Times Book Review)

2. Blight: Fungi and the Coming Pandemic by Emily Monosson

(W. W. Norton & Company)

1 Rave • 3 Positive

“Monosson commendably serves as a medical Paul Revere by persuasively warning us that dangerous fungi are already causing havoc among plants, animals, and humans, and more are on the way … Monosson thoroughly reviews the wallop of fungi on wildlife, including white-nose syndrome wiping out bats and the demise of frog populations from chytridiomycosis. Many kinds of trees are threatened by fungus (white pine blister rust, cedar-apple rust). Even the beloved Cavendish banana, is endangered by an aggressive fungus (fusarium wilt). Pathogenic fungi are experts at surviving. They make formidable foes. Neglecting these emerging organisms is truly hazardous to health.”

–Tony Miksanek (Booklist)

3. Kings of Their Own Ocean: Tuna, Obsession, and the Future of Our Seas by Karen Pinchin

(Dutton)

1 Rave • 2 Positive • 1 Mixed

“The descriptions of Amelia’s undersea wanderings are where Pinchin’s writing really comes alive, manifesting her passion for protecting all marine life. The author ends with a recap of current conservation efforts and a solemn reminder of how human actions too often interfere with fragile, interdependent ecosystems.”

–Kathleen McBroom (Booklist)

Our smorgasbord of superior reviews this week includes Walter Mosley on Colson Whitehead’s Crook Manifesto, Ron Charles on Richard Russo’s Somebody’s Fool, Xan Brooks on Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah’s Chain-Gang All-Stars, Dwight Garner on Ann Beattie’s Onlookers, and Rachel Connolly on Max Porter’s Shy.

“Crook Manifesto is a dazzling treatise, a glorious and intricate anatomy of the heist, the con and the slow game. There’s an element of crime here, certainly, but as in Whitehead’s previous books, genre isn’t the point. Here he uses the crime novel as a lens to investigate the mechanics of a singular neighborhood at a particular tipping point in time. He has it right: the music, the energy, the painful calculus of loss. Structured into three time periods—1971, 1973 and finally the year of America’s bicentennial celebration, 1976—Crook Manifesto gleefully detonates its satire upon this world while getting to the heart of the place and its people. This is a story of survival without redemption, where the next generation loses some of the well-honed instincts that have built this world … Whitehead bends language. He makes sinuous the sounds of a city and its denizens pushing against the boundaries. He can be mordantly funny … At other times, Whitehead gives his characters the quiet and room to issue forth the sound of such deep regret and resignation: of being trapped, of all the odds stacked against them, even from within.”

–Walter Mosley on Colson Whitehead’s Crook Manifesto (The New York Times Book Review)

“Russo has become our national priest of masculine despair and redemption. The gruff grace that he traffics in might seem sentimental next to the merciless interrogation of John Updike’s Rabbit series or the philosophical musings of Richard Ford’s novels about Frank Bascombe. But Russo understands the appeal, even the necessity, of those absurd affections that exceed all reason and make the travails of human life endurable … Donald Sullivan, whom everybody called Sully, is gone now, but his specter remains so prevalent in these pages that Somebody’s Fool is practically a ghost story. ‘He’s dead and gone,’ one character shouts in exasperation. ‘Does he have to haunt every single conversation we have?’ Yes, apparently. Sully’s old friends are still stumbling around in a reverie of fond memories and unhealed grief. I half expected them all to wear sport bracelets that ask, ‘WWSD?’ Their recollections and apostrophes are sweet, but they also freight the novel with an enormous burden of exposition. And if you haven’t read the previous two novels, you’re likely to feel as though you’re tagging along to your spouse’s college reunion. In trilogies, as in life, you had to be there.”

–Ron Charles on Richard Russo’s Somebody’s Fool (The Washington Post)

“Just as most hit TV shows plunder from material that has scored well in the past, so too does Chain-Gang All-Stars, which lifts freely from The Hunger Games and The Running Man, Rollerball and Battle Royale. Where it differs from more straightforward genre fare is in foregrounding what would normally remain as a political subtext. Adjei-Brenyah wants to highlight the factual springboards beneath his flights of fancy, providing footnotes to explain the intricacies of the 13th amendment, the psychological effects of solitary confinement and the 1944 state murder of 14-year-old George Stinney. Chain-Gang All-Stars, he stresses, isn’t fantasy at all. Instead, it’s a nightmarish burlesque about industrialised racism. The sheer weight of this supporting evidence—happily accommodated by the book’s maximalist style—frequently spins us off course. Alternating chapters roam far and wide, keeping tabs on a supporting cast of TV executives, ‘abolitionist’ protesters and a sceptical armchair critic who is slowly sucked in and converted. These cutaways give Chain-Gang All-Stars the bracing panoramic sweep of an old-school social novel in the vein of Steinbeck or Dos Passos, but the technique needs finessing. As it is, Adjei-Brenyah combines the winning confidence of a young artist who is unafraid to tackle an enormous canvas with the nervousness of a debutant who worries about leaving his reader with the same group of people for more than a few pages at a time. His plot is constantly interrupting itself to move us along and show us something new.”

–Xan Brooks on Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah’s Chain-Gang All-Stars (The Guardian)

“The Covid lockdown period already seems, as a subject, like a flattened corpse over which the whole of American culture and commentary has trampled. But it was only three years ago. Fiction is still catching up. A case in point is Onlookers, Ann Beattie’s new collection of stories, her best in more than two decades … The stories are about instability and shattered certainties … An almost comically wide cast of characters … The rap against Beattie, in sum, is that her work can be aimless, ‘twee,’ lacking in political and other convictions, plotless, a bit draggy. All feathers and no bird, marginalia in search of a thesis. She is too alert to the tender souls of the bolshy bourgeoisie, stirring groats on their Viking ranges. All these things are true at times, even in Onlookers. This book reminds you, more often, of why readers cared about her in the first place. She’s a dry yet earthy writer, in touch with moods and manners, with an eye for passing comedy … She takes notes on her species, as if she were a naturalist observing robins. She pries at the mystery of life. There’s a strong feeling of convergence in her best stories.”

–Dwight Garner on Ann Beattie’s Onlookers (The New York Times)

“This may sound like a story about how trauma begets dysfunction (a very well-trodden terrain for novels at present, as Parul Sehgal argued in “The Case Against the Trauma Plot”), but Porter does something fresher and more interesting than drawing a line between, say, a chaotic home life and bad behavior. There is nothing particularly (or even quite) bad in Shy’s memories of his upbringing at all. What Porter portrays instead is a pattern of slights and rejections, mostly caused by Shy’s social awkwardness and confusion about how to relate to other people … Shy’s backstory sits at odds with current trends in fiction and feels true to life in a way that the trauma plot often does not … Porter sets himself the challenge of rendering the least palatable of these children sympathetic: the kind of boy who has a lot going for him, a lot of privilege, and can’t seem to do anything but make a mess of it. Porter succeeds at this, in part because the distinctive fragmentary stream of consciousness style he has developed, first in Grief Is the Thing With Feathers, then in Lanny and The Death of Francis Bacon, fosters a close proximity between the reader and his characters and their emotional landscape. His technique of layering snatches of thought, memory, and feeling deftly, in a manner that feels instinctive, makes Shy’s perspective seem not only understandable but inevitable to the reader.”

–Rachel Connolly on Max Porter’s Shy (The New Republic)

Tessa Hadley’s After the Funeral, David Lipsky’s The Parrot and the Igloo, Nicole Flattery’s Nothing Special, and Laura Cumming’s Thunderclap all feature among the Best Reviewed Books of the Week.

1. After the Funeral by Tessa Hadley

(Knopf)

11 Rave • 4 Positive

Read an interview with Tessa Hadley here

“This new collection is a great introduction to her work and for those of us already familiar with Hadley, it’s a great addition. Throughout the collection, Hadley spins out character studies of (mostly) women at odds with themselves, their partners, their families, or life in general … Hadley does a wonderful job of weaving past and present together as the sisters are forced to confront their memories and relationships. And, of course, there are those moments of shining prose … Rife with deft and often beautiful prose, and astute but compassionate characterization, this is a wonderful collection.”

–Yvonne C. Garrett (The Brooklyn Rail)

2. Nothing Special by Nicole Flattery

(Bloomsbury)

4 Rave • 9 Positive • 2 Mixed

“Exquisitely disorienting … The book is driven by a kind of respiratory imagining, a panting projection that sustains both Mae and the story. She subjects her world and the people who populate it to a ravenous metamorphosing … Some might find the plot’s relentless dissociation a decelerator, but I found it brave and effective: Flattery remains so loyal to the physics of her character’s struggles, to the struggle of storytelling itself, that she is willing to risk allowing the less committed reader to wander off. The point of this novel is not illumination; it’s almost an accident that we get to know Mae at all. Instead the novel captures, in gorgeous prose, the happy and unhappy coincidences that allow us to fall into knowing, those unexpected snags that trip us into ourselves … A revelation that is also distinctly anti-revelation, by a writer whose withholding is as vivid as her bestowing, who shows a story for what it is—something real, something fabricated, something to hide in and from, something special, something so utterly unremarkable it’s the only thing that matters.”

–Alice Carrière (The New York Times Book Review)

3. Ripe by Sarah Rose Etter

(Scribner)

5 Rave • 1 Positive

“Masterfully juxtaposing ‘wild amounts of wealth’ with ‘extreme poverty and displacement,’ Etter examines deep inequities in an image-obsessed, capitalist society. Her biting social commentary layers horror with dark comedy, using vivid imagery and striking language to great effect. Readers will savor this astonishing tour de force..”

–Rebecca Hopman (Booklist)

**

1. Thunderclap: A Memoir of Art and Life & Sudden Death by Laura Cumming

(Scribner)

8 Rave

“Genre-defying … Cumming suggests that we recall the past through pictures … Cumming clearly loves these paintings, and by weaving together vivid evocations of ones that particularly move her with brief biographies of the men and women who painted them, she invites us to share that love … Like all good elegists, Cumming, too, brings the dead to life in the very act of mourning them.”

–Ruth Bernard Yeazell (The New York Times Book Review)

2. Tabula Rasa by John McPhee

(Farrar, Straus and Giroux)

5 Rave

“A charming, breezy collection of reminiscences about projects that didn’t make it, ideas that never got fully baked, research never written up, either because the subject died or because McPhee, who was born in 1931, lost interest along the way … Few of the subjects discussed in Tabula Rasa call out for the longform treatment; McPhee’s instincts (and editors) steered him well. But there are still pleasures to be had in these 50 short chapters. Minor league McPhee is still major league writing. It’s not faint praise to say he is still more pleasingly consistent than any other writer working. There is never a dud metaphor, never a cliché … He still has stories to tell. Maybe they’re just not the ones he had the good sense to let go.”

–Mark Oppenheimer (The Washington Post)

3. The Parrot and the Igloo: Climate and the Science of Denial by David Lipsky

(W. W. Norton & Company)

4 Rave • 1 Positive

“A tour guide to the vicissitudes of climate change … The tone and language of this book bounces between inviting (it is an excellent, approachable primer on the science of global warming) and irritating (the informality is at odds with the urgency of the argument). That almost certainly reflects how infuriating it must have been to trace the evolution of an idea that is a challenge to human survival … The virtue of this volume lies in Lipsky’s dizzying account of how long we have known so much about an issue that means so much, how long we have ignored a problem that has begged not to be ignored, how much time we have wasted when time was of the essence, how clear the danger was when the opponents repeatedly asked for further clarity, how undeniable and how urgent the threat is now due to the peregrinations of the deniers”

–David Shribman (The Boston Globe)

Our feast of fabulous reviews this week includes Peter C. Baker on Nicole Flattery’s Nothing Special, Joyce Carol Oates on Ursula Parrott’s The Ex-Wife, Lauren LeBlanc on Tessa Hadley’s After the Funeral, Hari Kunzru on Djuna’s Counterweight, and Casey Cep on Tennessee Williams’ The Caterpillar Dogs.

“This description, I’m aware, might call to mind a certain mode of historical fiction that feels awkwardly stuck between narrative art and Wikipedia—the kind of novel where you feel the author’s presence as a tour guide, always nervously looking over their shoulder, dropping more period detail and context to make sure you’re learning what you’ve come to learn. Nothing Special is nothing like that … Flattery manages to cannily anatomize the famous artist’s powers and appeal while simultaneously pushing the man himself almost entirely out of the frame. It’s a method that the book uses more than once—sneaking up on its subjects from odd angles, as if distrustful of more direct paths … In Flattery’s first book, the prose sometimes seemed so intent on preëmptively repelling false hopes or unearned optimism that it functioned not just as armor but also as a straitjacket, limiting the registers of feeling the stories we’re able to access. Nothing Special is a richer, more flexible undertaking … Just as Nothing Special is a great book about Warhol with almost no Andy Warhol in it, so too is it a sneakily moving homage to human kindness, where kindness appears only in quick flashes and never solves anything. The possibility of real connection feels almost hidden, as if Flattery herself were afraid of making too much of it.”

–Peter C. Baker on Nicole Flattery’s Nothing Special (The New Yorker)

“Seemingly out of nowhere, precociously aphoristic and coolly unsentimental, the debut novel Ex-Wife appeared in 1929 to much scandalized acclaim; originally published anonymously, it brought a life-altering celebrity to its hitherto unknown author, Ursula Parrott, just thirty years old, who found herself not only controversial and an immediate best seller but, more questionably, something of a spokesperson for the ‘new woman’ of the era—a female counterpart to her almost exact contemporaries Ernest Hemingway and F. Scott Fitzgerald. In the trajectory of her career as in its vicissitudes, Parrott is more akin to Fitzgerald than to Hemingway, whose expatriate characters and stark themes of war, manly valor, and the ubiquity of death-in-life take him far from the domestic dramas of romantic disillusion, marital strife, and divorce that preoccupied Parrott and Fitzgerald and made them, each for a vertiginous while, rich. Like Fitzgerald but from a woman’s perspective, Parrott examined the fraying social fabric in the aftermath of World War I, the final vestiges of a Victorian era in which the place of a woman was defined almost exclusively in reference to men: fathers, husbands, ex-husbands, lovers … Ex-Wife is a sharply observed, intimate account of a failed marriage, several failed love affairs, an abortion, numerous alcoholic interludes and one-night stands, and an abrupt, pseudohappy ending when the ex-wife decides, for purely pragmatic reasons, to marry a man she doesn’t love…At its most entertaining Ex-Wife is a Broadway play in novel form, with briskly clever dialogue tending toward the comic-aphoristic, as if Dorothy Parker, Noël Coward, and Oscar Wilde had collaborated to examine the war between the sexes in the post-Victorian era.”

–Joyce Carol Oates on Ursula Parrott’s The Ex-Wife (The New York Review of Books)

“Impeccably literary, emotionally satisfying, yet unexpectedly unsettling … Hadley always delivers fiction that cuts to the quick … It could sound like a slight to be called dependably brilliant, but unquestionably, that’s what she is. She writes with an unrushed assurance and confidence that breeds comfort … In her short stories, there’s less space to tone and then flex those literary muscles. It is essential to be nimble. While her novels are exquisite, knitted with plot and deep character development as well as a keen sense of space, her short stories lose nothing of that depth in their brevity. Hadley’s stories flicker vividly as powerful vignettes that compress personal histories, offering the reader entry into a brief period of time in which the characters upend perceptions.”

–Lauren LeBlanc on Tessa Hadley’s After the Funeral (The Boston Globe)

“While never as deeply mired in paranoia as the vertiginously indeterminate fictions of Philip K. Dick, this is a world where agency and identity are always in doubt. Do these feelings of love belong to you or have they been planted? Is the terrorist acting of his own volition, or is he a meat-puppet, under the sway of shadowy controllers elsewhere? … From the rainy neon of Blade Runner to the Vanta-Black corporate Japan of Neuromancer, Anglophone near-future speculation has long had a streak of Orientalism, a fascination (often admiring) with the liquid modernity of East Asian urbanism, and the distinctiveness of the region’s approaches to technology. After the global success of Cixin Liu’s Three Bodies trilogy, American publishers are belatedly bringing Asian science-fiction narratives to an Anglophone readership that has a demonstrable hunger for its culture in various forms. Counterweight is also, in a small way, an expression of soft power, part of a wave of South Korean film, popular music and literature that has in recent years given Seoul an unprecedented global cultural clout … The novel’s speculations about human agency resonate in the current moment, when American tech C.E.O.s oscillate between issuing sonorous warnings about the existential risks of the A.I. systems they’re developing and breathless hype about brain-computer interfaces.”

–Hari Kunzru on Djuna’s Counterweight (The New York Times Book Review)

“The deeper questions about Williams’s transformation are the stuff of endless debates and dissertations, fuelled by interviews, letters, memoirs, biographies, and Williams’s own writing, including posthumous publications. Most of us don’t mind literary grave robbing, especially when it comes to authors we love, in which case we don’t mind cradle robbing, either: the boyhood diary of F. Scott Fitzgerald, the miniature books of the young Brontë sisters, the childhood newspaper of Virginia Woolf. In this spirit, New Directions is publishing a volume of the early work of Tennessee Williams, who died forty years ago. Slightly less jejune than the abovementioned efforts, this set of short stories is more like the university-era poetry written by T. S. Eliot in the notebook he titled Inventions of the March Hare, or Vladimir Nabokov’s blank-verse play The Tragedy of Mister Morn, which he wrote as a twentysomething … Like the early sketches of a great portraitist, these stories feature the outlines of the characters—spinsters, sirens, hotheads, and ministers—whom Williams later made famous in plays like The Glass Menagerie, A Streetcar Named Desire, and Cat on a Hot Tin Roof. The promise of juvenilia is that it will reveal how the person became the artist, exposing the sometimes awkward process by which he fashioned himself through apprenticeship and experimentation. The Caterpillar Dogs fulfills that promise, but its real appeal is something else entirely: not a revelation but an affirmation, the chance to be reminded of what we loved about Williams in the first place.

–Casey Cep on Tennessee Williams’ The Caterpillar Dogs: And Other Early Stories (The New Yorker)

Patrick DeWitt’s The Libraianist, Charlotte Mendelson’s The Exhibitionist, and Beth Nguyen’s Owner of a Lonely Heart all feature among the Best Reviewed Books of the Week.

1. The Exhibitionist by Charlotte Mendelson

(St. Martin’s)

6 Rave • 3 Positive • 1 Mixed

“Both a roiling family drama and a chilling portrait of enmeshment, coercive control and enabled addiction. Mendelson’s heady present-tense narration mingles eroticism, absurdity and pathos, capturing the intensity of illicit love, the corrosiveness of bullying, the bottomlessness of narcissism. Her similes a volley of bullseyes, her tonal chiaroscuro sharp, she darts rapidly between perspectives, ratcheting up the tension as we hurtle to the finale.”

–Madeleine Feeney (The Telegraph)

2. The Librarianist by Patrick DeWitt

(Ecco)

3 Rave • 5 Positive • 2 Mixed

“I think each Patrick deWitt novel is going to be the one that helps everyone fall in love with his writing, but The Librarianist could finally do it … DeWitt’s dialogue moves with the speed and precision of great conversation and its jokes sneak up on you, more like a wisp of wind on your cheek than someone tapping you on the shoulder to tell you something funny … Bright and entertaining from beginning to end.”

–Chris Hewitt (The Star Tribune)

3. Pete and Alice in Maine by Caitlin Shetterly

(Harper)

2 Rave • 3 Positive • 1 Mixed

Read an essay by Caitlin Shetterly here

“Tender … Shetterly is attuned to quicksilver changes in the family dynamic … Shetterly is particularly good at showing how caring for children can test a relationship … Shetterly does not allow Pete the airtime she grants Alice. We get three third-person chapters from Pete’s point of view and nine first-person chapters narrated by his wife … In certain moments, Shetterly’s debut achieves a subtle grace, a quality of light and shadow worthy of a Bergman film.”

–Allegra Goodman (The New York Times Book Review)

**

1. Owner of a Lonely Heart by Beth Nguyen

(Scribner)

3 Rave • 4 Positive

“Nguyen is a confident and reliable protagonist even when running up against painful memories, providing readers with enough distance as to almost be objective … Nguyen has made a journey of facing her origins and contending with the limitations of American narratives, and we are lucky to be invited along the way.”

–Mai Tran (The Brooklyn Rain)

2. The Light Room by Kate Zambreno

(Riverhead)

1 Rave • 6 Postive

Read an interview with Kate Zambreno here

“Zambreno’s writing is sharpest, most emotionally alive, when it drills into that interior landscape … Woven into these moments are ruminations on natural history, education and the work of other writers and artists … Readers looking for sturdier insights into what the virus has meant for human history are unlikely to discover them here. But there is comfort and intimacy to be found in the nest Zambreno builds, with lint and marbles and straw, the objects that matter in her tiny universe. Its achievement is as a sustained narrative of noticing.”

–Eleanor Henderson (The New York Times Book Review)

3. The Red Hotel: Moscow 1941, the Metropol Hotel, and the Untold Story of Stalin’s Propaganda War by Alan Philps

(Pegasus Books)

3 Rave • 2 Positive

“A sizzling read full of bitchiness and high jinks. But it is also a deeply moral book, outlining a simple truth: that the press pack abroad often operates in a bubble and is deeply dependent on local translators and fixers. Philps… has an eye for detail … There are obvious parallels to Vladimir Putin’s arbitrary arrests, his use of visa restraints against journalists, Russian state media’s fake news, and the depiction of critics as enemies of the state. Philps doesn’t labour the comparisons, but any reporter who has had to operate in a pack while covering a dictatorship will feel a twinge of recognition, and perhaps of guilt.”

–Roger Boyles (The Times)

Our basket of brilliant reviews this week includes Fintan O’Toole on Mark O’Connell’s A Thread of Violence, Idra Novey on Domenico Starnone’s The House on Via Gemito, Ginny Hogan on Josh Hawley’s Manhood, Dan Pipenbring on Dan Schreiber’s The Theory of Everything Else, and Darryl Pinckney on Alston Anderson’s Lover Man.

“[O’Connell] comes to the story, essentially, through the veil of fiction. He did a PhD on Banville and it was via The Book of Evidence that he became fascinated by the man whom the novelist had transformed into Montgomery. With other violent events, this might be a terrible place to start. It suggests a dreadful essay in postmodern cleverness, where there is no distinction between what happened and how it is represented, and morality is an embarrassing anachronism. But nothing could be further from O’Connell’s intent; in this weird case, the impulse to explore and unravel fictions is just the right instinct. It gives O’Connell, when he tracks down Macarthur (who has been around Dublin since his release from prison in 2012) and gets him to tell his own story, a heightened awareness that it is indeed precisely that: yet another story, another linguistic construct in which the relationship between truth and fiction is murky, unstable and impossible to pin down with any certainty … O’Connell is acutely conscious of the moral ambiguity of giving a voice to a man who does not really take responsibility for his vile acts but rather, as O’Connell puts it, accepts that he committed murder but does not accept that he is a murderer … This is what makes A Thread of Violence such a remarkable book. If it begins in the genre of ‘true crime’—let’s find the murderer and see if he will tell us what happened—it becomes an exploration of the human capacity to avoid truth … the book itself is haunting in its dissection of the mechanisms that allow human beings to dehumanize others.”

–Fintan O’Toole on Mark O’Connell’s A Thread of Violence: A Story of Truth, Invention, and Murder (The Irish Times)

“Starnone is a writer exquisitely attuned to class anxieties: As his later novels do, Via Gemito explores the emotional cost of class mobility, and the psychic toll of changing one’s speech patterns and behavior for the sake of social and financial gain … Nowhere is the emotional toll of his shapeshifting more clearly on display than in a scene from Mimí’s adolescence, when he begins to try on different voices and behaviors, and adopt the mannerisms of relatives and strangers. One day, he arrives at church wearing a tunic his mother has cut as short as a girl’s dress. There, he ends up performing the female part in a dance with a classmate, a muddling of gender roles that leaves him feeling so humiliated that he begins to see himself not as a physical form, but as ‘an intimate sigh, a moan.’ Shame, this scene suggests, is a powerful psychic trap, and the only reliable way out is through acts of imagination. It’s a stirring memory for an adult male narrator to share, one that stayed with me as vividly as the wary gaze of the Neapolitan mastiff that Federí paints after dark, with its large muzzle and piercing eyes.”

–Idra Novey on Domenico Starnone’s The House on Via Gemito (The Atlantic)

“Josh Hawley, best known for fleeing a mob he helped incite, has written a book on manhood. In Hawley’s defense, he began writing the book before everyone found out about the running-away situation. But it was, unfortunately, after he did the running … To be honest, I’m not sure I can imagine a less productive message than encouraging men to become fathers before they’re ready. Hawley is only interested in helping men live the exact same life that he himself leads, even if that life isn’t available (or even desirable) to them. According to recent studies, it turns out that a slight majority of Americans did not attend Yale Law School or receive campaign donations from Peter Thiel. No one, myself included, should read this book … A consistent through line in Manhood is Hawley’s unsettling obsession with restraint. He clearly takes pride in his own body, evidenced by the inclusion of a gratuitous story about strangers asking him if he were an athlete. The only thing he apologizes for—in the entire book—is letting his kids eat doughnuts once a week. In villainizing the Epicurean left, he argues that self-control is the solution … I started this review by making fun of Hawley for running away from the January 6 insurrectionists. And we should never stop making fun of that. But we can’t let it be the only thing people know about him. Running from danger isn’t the worst thing he’s ever done, and I’m not sure who would have benefited if Hawley had stood his ground and started swinging fists at the rioters at the Capitol. It’s what he did before and after that. There are many different ways to be a man, but the type we need is someone who takes responsibility for his actions. Here are Hawley’s actions: All he’s done, for his entire career, is pin the blame on anyone but himself. By that standard of manhood alone, I feel comfortable saying Hawley’s not one.”

–Ginny Hogan on Josh Hawley’s Manhood: The Masculine Virtues America Needs (The Nation)

“The rise of the search engine, reference text ad infinitum, spelled doom for many books such as these. So it’s a pleasure to encounter Dan Schreiber’s The Theory of Everything Else: A Voyage Into the World of the Weird, a willfully miscellaneous survey of the bizarre beliefs that people have held over the centuries: the kind of random, strange-for-the-sake-of-strange compendium that’s seldom published anymore. Here, united in a single volume, are hollow-Earthers, plant-talkers and Satanists; here is the inventor of a bean that causes less flatulence; here is ‘the world’s first pubic louse hunter.’ The Theory of Everything Else isn’t quite a reference text—it lacks so much as an index—but its aimless esoterica makes it feel like one. I mean that as a compliment. I can imagine needing to consult this book in the middle of the night, though I can’t imagine why … By now you can see that The Theory of Everything Else is all over the map. Its broadness is mainly an asset—it makes the book suitable for beach reading or for mainlining before a dinner party. Schreiber brings a formidable amount of research to bear, and he’s careful never to mock any of his subjects, even those who may deserve it. But he’s sometimes too adept at quarantining the weirdness, too certain of where the rational ends and the irrational begins. Readers who feel that it’s possible, even beneficial, to believe something and disbelieve it at the same time will wish that he had more to say about his own attraction to Chiroptera. Knocking around somewhere amid his skepticism is a head-spinning story about the nature of belief: about how simple it is to pick up or abandon the ideas that dictate our basic orientation toward the world.”

–Dan Pipenbring on Dan Schreiber’s The Theory of Everything Else: A Voyage Into the World of the Weird (The New York Times Book Review)

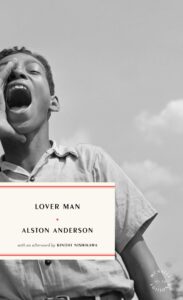

“Black talk is again on the move in Lover Man, a newly reissued collection of melancholy stories by Alston Anderson originally published in 1959. Alston Anderson is one of those lost names of twentieth-century African American literature. In our present cultural mood of generous reexamination, the hunt is on for the forgotten, the overlooked, the could have been, and there among them is Anderson … It took Anderson a while to get Lover Man together—a much-praised literary takeoff. However, his was the brief flight of a self-destructive soul, and before long his name had sunk in the darkness … While Ellison’s presence is on every page of Invisible Man, Anderson in Lover Man heads in the other direction, as if already in pursuit of his own disappearance … Anderson begins somewhere in the Black Belt, in the 1930s of people having to chop wood for the kitchen stove. His style is straightforward, but the simplicity is deceptive, the calm surface at odds with the depths sending up their clues … Writers are not dialectologists. The sound of Anderson’s Deep South is a work of the imagination. He came from the Canal Zone to the Upper South, not the Black Belt, but his ear, like Hurston’s, can be faultless. An Anderson story can be in the form of a lie, and then within that lie he has a character tell a lie. Folklore as language is a collective experience, a symbol of identity, a dialect maintained by common experiences. Yet although most of Anderson’s stories are set in the South, Lover Man has considerable interest as a portrait of black postwar migration from the lusty, incestuous-feeling, small-town South to the war-changed streets of Harlem, where there is bebop and heroin and a boxer answering the door in his underwear who is maybe also rough trade.”

–Darryl Pinckney on Alston Anderson’s Lover Man (The New York Review of Books)