Put your March Madness brackets aside for a moment, folks, because baseball’s opening day is upon us. Yes, the winter snows have melted, spring training has sprung and gone, and teams across America—from the storied Sox and Yankees, to the scrappy Minor League franchises, all the way down to the lovable little league outfits—are dreaming of winning it all.

And it’s not just the athletes who are prone to flights of fancy. From Bernard Malamud’s The Natural to Chad Harbach’s The Art of Fielding, baseball glories also occupy a special place in the American literary imagination. With that in mind, and before the crushing disappointment of another lost season sets in, here are ten great books about the country’s national pastime.

Play ball!

*

Fiction

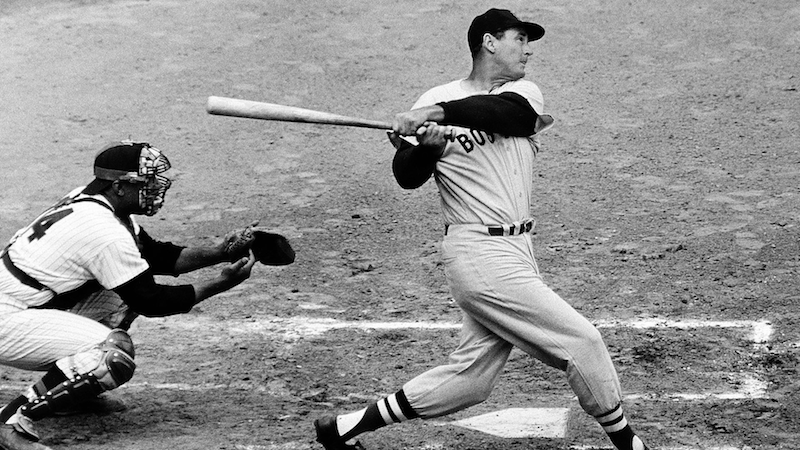

The Natural by Bernard Malamud (1952)

“Back in the Thirties the baseball writers making the swing through the West with major league teams occasionally wondered whether one of their number would ever produce a serious novel about baseball. That novel has finally been written and if the author does not come from the ranks of baseball reporters, at least he hails from Brooklyn and there are those who feel that qualifies him ex officio.

It’s an unusually fine novel, too, although I don’t know how the professionals are going to take it. For Bernard Malamud’s interests go far beyond baseball. What he has done is to contrive a sustained and elaborate allegory in which the ‘natural’ player who operates with ease and the greatest skill, without having been taught is equated with the natural man who, left alone by, say, politicians and advertising agencies, might achieve his real fulfillment.

…

“All the story is here of a natural man—hurt badly by his first love, recovering late for his profession, almost achieving greatness, then distracted or betrayed by people or objects or events all equated with elements in our environment. In his telling and always deliberate use of the vernacular alternated with passages evocative and almost lyrical, in his almost entirely successful relation of baseball in detail to the culture which elaborated it, Malamud has made a brilliant and unusual book.”

“Bang the Drum Slowly is the finest baseball novel that has appeared since we all began to compare baseball novels with the works of Ring Lardner, Douglass Wallop and Heywood Broun. If you enjoyed Mr. Wallop’s The Year the Yankees Lost the Pennant you may like this enjoyable horsehide opera all the more, because here Mr. Wallop’s cherished Washingtonians are saved by no such supernatural means as he gave them in his novel, now transmogrified to the musical stage as Damn Yankees.

In its elementals, Bang the Drum Slowly has two familiar themes. One is the story of the way a doomed man may spend his last best year on earth. The other is the story of how a quarrelsome group of raucous individualists is welded into an effective combat outfit.

…

“If the coming season is as exciting as the one in Bang the Drum Slowly we may all look forward to a new lease on life for major league baseball, the fabulous invalid of sports. The main occupational malady of a novel about it—the necessity for describing one game after another—is relieved, here, by skillful diversionary measures. There are all sorts of feuds and alliances among the players and the front office. There is the Damoclean question of Bruce Pearson’s survival. There is Wiggen’s own teeming private life. There is the epochal, in its own dimensions, doubt that one of the Mammoths will overtake Babe Ruth’s home-run record. All in all, this is a book for the books.”

–Charles Poore, The New York Times, April 17, 1956

The Great American Novel by Philip Roth (1973)

“A book with this title just had to be written, and who is better qualified (if not Norman Mailer?) than Philip Roth, who’s been doing his damnedest ever since Goodbye Columbus got the National Book Award back in 1959 when Ike was President. And what could be the topic but that ex-favorite National Pastime—what every healthy American boy did Sunday afternoons before the advent of football and dope. The book is the purported history of the demise of the Patriot League, told by an Irish (natch) sportswriter name a’ Word Smith, whose endless alliteration makes Joyce look like a slouch—centering on the Exile of the Chosen People, the Ruppert Mundys (Rupe-it, in New Jerseyese) who in the bleak war years (that’s World War Two) had a one-legged catcher, a one-armed right fielder (catches the ball, sticks it in his mouth, throws off the glove, takes the ball out of the mouth, throws to home), a midget pitcher, a fourteen year-old 92 pound second bagger. . . possibly part of the Commie conspiracy to destroy the League, hence baseball, hence America. Truth told by Word Smith from the confines of his old-age home, where he competes with superstars Melville, Twain, and Hawthorne in writing the you-know-what. A self-conscious savage satire of the land of apple pie and wheaties, plus occasional foul tips at literary tradition from Gilgamesh on up. As for the G.A.N., it is as much a dream as the 500 hitter, a goal made mythical by an arbitrary set of rules for a game which we (both writers and readers) now find tiring.”

Shoeless Joe by W.P. Kinsella (1982)

“W.P. Kinsella was born for fiction, or at least for this book. Shoeless Joe concerns a moonstruck man named Ray Kinsella (Should we presume a kinship between author and protagonist? You bet we should) who hears voices and heeds what they say. First, Ray builds a ball park on a few acres of his Iowa corn farm and populates it in his mind with the disgraced heroes of the 1919 Black Sox, most notably Shoeless Joe Jackson … Mr. Kinsella is drunk on complementary elixirs, literature and baseball, and the cocktail he mixes of the two is a lyrical, seductive and altogether winning concoction. It’s a love story, really the love his characters have for the game becoming manifest in the trips they make through time and space and ether.

…

“Long after I finished reading it, I found myself seeing—and believing—J.D. Salinger horsing around with Ray and Moonlight Graham in a darkened ball park in Minnesota. And I decided that Salinger must be a far more likable man than his anchorite image would attest. I throbbed with the pain visited on the reputation of Joe Jackson and reveled in the pleasure he could now find on his nightly return to the cornfield diamond. And I understood—passionately—what Ray meant when his identical twin, Richard, no baseball fan, came to the cornfield and saw no diamond, saw no Black Sox, saw no Moonlight Graham, while Ray and Salinger and Kid Scissons sat enthralled: ‘Richard’s eyes,’ Ray said, ‘are blind to the magic.’

W.P. Kinsella, gazing at baseball, sees the magic plain.”

–Daniel Okrent, The New York Times, July 25, 1982

The Art of Fielding by Chad Harbach (2011)

“Chad Harbach’s book The Art of Fielding is not only a wonderful baseball novel—it zooms immediately into the pantheon of classics … Mr. Harbach has the rare abilities to write with earnest, deeply felt emotion without ever veering into sentimentality, and to create quirky, vulnerable and fully imagined characters who instantly take up residence in our own hearts and minds … Mr. Harbach skillfully constructs a story with startling depth of field. Although his novel is strewn with literary allusions, it wears its literary borrowings lightly, focusing instead on the inner lives of its characters … What makes The Art of Fielding so affecting is that it captures these people at that tipping point in their lives when their dreams, seemingly within reach, suddenly lurch out of their grasp (perhaps temporarily, perhaps forever), reminding them of their limitations and the random workings of fate.”

–MIchiko Kakutani, The New York Times, September 5, 2011

*

Nonfiction

Ball Four by Jim Bouton (1970)

“Bouton shook up the stagnant, tradition-bound, image-conscious world of major-league baseball simply by telling the truth. Yet reading Bouton’s seminal tome nearly 40 years after its release, I was struck by how relatively tame it is, and by its fundamental sweetness. Bouton wasn’t an angry punk who wanted to destroy baseball. He was a fiery idealist who passionately loved the game and was frustrated that it so often failed to live up to its ideals.

…

“Bouton chronicles a game in a profound state of flux. The times were changing outside the ballpark, but the major-league mindset seemed stuck somewhere in the mid-’50s. The old guard still ruled with crew cuts, knee-jerk patriotism, reactionary politics, and near-religious belief in the necessity of maintaining the status quo.

So you can only imagine how threatened they were by a guy who not only reads books, but writes them, loves Ralph Nader, and is passionate about unions and protesting apartheid. In Ball Four, which certainly skirts self-aggrandizement at times, Bouton seems intent on single-handedly dragging baseball kicking and screaming into the late ’60s.

…

“Ball Four became a controversy magnet and a pop-culture phenomenon at the time of its release because it was shocking, sexy, and irreverent but it’s endured because of the substance and sweetness behind the not-as-sordid-as-you-probably-imagine revelations. And also because it’s fucking great. It’s undoubtedly better to be a baseball fan if you want to dig Ball Four, but you don’t have to be. You just have to like a great story wonderfully told.”

–Nathan Rabin, The AV Club, April 17, 2009

The Boys of Summer by Roger Kahn (1972)

“If you are old enough or were fan enough to remember the heady, magnetic, brash Brooklyn Dodgers of the early ’50’s, Roger Kahn’s story will have special appeal; but if you lived on your fingernails following those magnificent bums, hanging on each pitch which you literally had to do (twice in a row, 1950 and 1951, the team blew the pennant in the last inning of the last game of the season), agonizing like a small Lear over their defeats and cheering yourself silly when they won, Kahn’s book is your book. Roger Kahn recalls how he found his way to the Dodgers, first as a boy growing up in Brooklyn near Ebbets Field, later as a young Herald Tribune reporter covering the team during 1952-53, pennant years though each time the Brooks dropped the series to the hated Yankees. Traveling with the club, he shared the players’ obscene language, heard the vicious race talk (the Robinson Dodgers were always ‘monkey-fuckers’ to some), drank with them, and once saw the great Furillo lying helpless on a table after being hit by a Sal Maglie fastball. But Kahn’s book is more than a baseball reminiscence—he sinks into his own past to get a handle on the present, lately realizing that ‘I covered a team that no longer exists in a demolished ball park for a newspaper that is dead,’ and he begins to consider the Dodgers ‘not as baseball players but as baseball-playing men.’ Kahn proceeds to seek out all those boys of his summer who are now in their forties and fifties: Duke Snider, Billy Cox, Preacher Roe, Shotgun Shuba, Carl Erskine, Joe Black, Campy, and of course Robinson of whom Durocher said ‘This guy didn’t just come to play. He come to stuff the goddamn bat right up your ass.’ Kahn talks to them about old times, the great moments, the feuds, the epithets; they remember, all of them, and at the end Kahn knows that he has grown up: ‘Wandering among old Dodgers I again heard the echoing Shakespearean theme: Fathers perish to make room for sons.’ And you too will make room for The Boys of Summer.”

–Kirkus Reviews, March 29, 1972

Summer of ’49 by David Halberstam (1989)

“For people in their 50’s now, the summer of 1949 was the morning of life, when to be young (and a Yankee fan) was very heaven. That summer was supposed to belong to the Boston Red Sox, with Casey Stengel, thought to be a clown, newly installed as Yankee manager, and Joe DiMaggio out of the opening-day lineup with bone spurs in his foot.

It was, as a broadcaster observes in this irresistible sports history, ‘the last moment of innocence in American life.’ The book’s author, David Halberstam, adds that the pace of living would soon accelerate ‘from the combination of endless technological breakthroughs and undreamed-of affluence in ordinary homes.’ The opening game of the World Series that autumn would be the first baseball game televised to a mass audience, so the character of the game would soon change.

…

“Reconstructing the race of ’49, Mr. Halberstam has gone behind the scenes and talked to every living veteran of the season except Joe DiMaggio, who the author says avoided his every approach. We learn of the tensions and passions that drove the two teams, and the strengths and peculiarities of a remarkable cast of characters … Forty years later, it’s all like yesterday.”

–Christopher Lehmann-Haupt, The New York Times, May 8, 1989

Moneyball by Michael Lewis (2003)

“Mr. Lewis is a terrifically entertaining explicator. Like Tom Wolfe, he can be trusted to make anything interesting, and to cast even the familiar in a bright new light. You need know absolutely nothing about baseball to appreciate the wit, snap, economy and incisiveness of his thoughts about it … Mr. Lewis has turned the story of one underfinanced baseball team into a showcase for his wide-ranging talents. Here he finds colorful characters, cutting-edge analytical data, the excitement of innovation and the thrill of the game, all bound together by the vigor of his prose. And in the person of Mr. Beane—who, one of his former teammates said, ‘could talk a dog off a meat wagon’—he has an irresistible underdog for a hero.

…

“While Mr. Lewis carefully explains and illustrates these developments, he also stays closely attuned to the spirit of the game. ‘Somewhere in the night sky is a ball,’ he writes, watching one player. ‘Where, apparently, he is unsure.’ Moneyball moves nimbly between sheer exuberance and strategic wiles. Some sections of the book concentrate on particular players and games, capturing them with lively immediacy

“The bottom line: in the American League West last year, the teams finished in inverse order to their payrolls. Oakland wound up ranking highest with the least money, demonstrating a principle that can be appreciated far beyond the realm of baseball. And Mr. Lewis has hit another one out of the park.”

–Janet Maslin, The New York Times, May 12, 2003

The Last Boy by Jane Levy (2011)

“…as she did in her innovative biography Sandy Koufax, Jane Leavy has found a different path through the throng. For her portrait of Koufax, she alternated an inning-by-inning account of that great pitcher’s perfect game in 1965 with deeply researched and fluidly written examinations of the rest of his life and import. The Last Boy, a nonlinear biography, takes the form of 20 days in Mantle’s life (something of a conceit; some of the ‘days’ are stretched to cover nearly a season, or an entire childhood). The approach refreshes and underscores the facts and patterns of a life, and enables Leavy to connect the dots in new and disturbing ways. The Mantle who emerges is perhaps more whole than ever previously captured.

…

“This is not, however, a dark book, no matter how dark parts of the life it portrays surely were. The hero worship of the fans, and the women who constituted a kind of endless batting practice in Mantle’s life, are presented thoroughly and fairly. There are revelations of hidden charity and great empathy, of a hero’s genuine inability to understand what others saw in him, and deeply endearing self-deprecating humor, even when a drunken Mantle is literally in the gutter. Almost everyone in sports over 40 has a ‘When I met Mickey’ story, and Leavy weaves her own through five vignettes interspersed with the main chapters. Hers is too sweetly, horribly, blissfully, embarrassingly Mantlean to give away here.

…

“Leavy comes as close as perhaps anyone ever has to answering ‘What makes Mantle Mantle?’ She transcends the familiarity of the subject, cuts through both the hero worship and the backlash of pedestal-wrecking in the late 20th century, treats evenly his belated sobriety and the controversial liver transplant (doomed mid-surgery by an oncologist’s discovery that the cancer had spread), and handles his infidelity with dispassion. Sophocles could have easily worked with a story like Mantle’s—the prominent figure, gifted and beloved, through his own flaws wasteful, given clarity too late to avoid his fate. Leavy spares us the classical tragedy even as she avoids the morality play. The Last Boy is something new in the history of the histories of the Mick. It is hard fact, reported by someone greatly skilled at that craft, assembled into an atypical biography by someone equally skilled at doing that, and presented so that the reader and not the author draws nearly all the conclusions.”

–Keith Olbermann, The New York Times, October 15, 2010