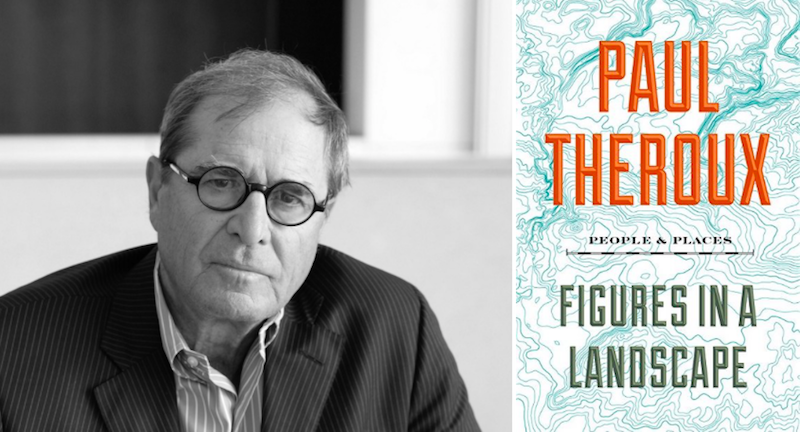

Paul Theroux’s new collection of essays, Figures in a Landscape: People & Places, is out this week from Eamon Dolan/Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. We asked the legendary travel writer to talk about five books in his life and he chose some companions for the road.

*

Apsley Cherry-Garrard, The Worst Journey in the World

A heroic journey in the dead of the Antarctic winter to locate the rookery of the emperor penguin. The most detailed and most humane account of Scott’s expedition.

Jane Ciabattari: Cherry was, I gather, the only survivor of Scott’s 1910 expedition to the South Pole? What makes the book memorable? In terms of being what you describe as the best approach for travel writing-“unofficial travel”-did it make a difference that he was a junior member of the expedition, less “official” than Scott?

Paul Theroux: He was not “the only survivor.” Scott and his small group died on the way back from the Pole. All the others on the expedition made it home alive, but Cherry was the youngest of them (only 21), not robust, and with poor eyesight. He was an amazing man, and at the end of the expedition he joined the army and fought in WWI, which weakened him further, and made the book harder to write. Yet he went on “the worst journey” to find the Emperor Penguin rookery and this was done in complete darkness and temperatures in the minus 70s F. His book is a record of the whole expedition, an analysis of Scott’s (flawed) character, and a brilliantly written but modest account of heroism. He was a neighbor and friend of G.B. Shaw, who also praised the book; ditto T.E. Lawrence (of Arabia) whom he knew.

Herman Melville, Typee

The book that made Melville famous. A castaway in the Marquesas with a shrewd assessment of Honolulu in the 1840s.

JC: Has living in Hawaii changed your sense of Typee? Have you retraced Melville’s steps?

PT: Living in Hawaii has made me admire Typee more-especially for the way Melville satirizes missionaries (how they are pulled along the bumpy roads by struggling Hawaiians). When I traveled in the Pacific for my book The Happy Isles of Oceania I took a ship to the Marquesas and spent some time in the islands, including Nuku Hiva, and the Tai-pi Valley, where Melville had lived among the people and frolicked with (so he claims) the lovely Fayaway. His book is a true adventure, full of incident, and it was his most admired one in his time. Melville’s career is strange-his books became less and less popular (Moby-Dick was a critical failure) and he died in utter obscurity.

Rebecca West, Black Lamb and Grey Falcon

Many people believe this to be the greatest travel book ever written. 400,000 words, all of them well-chosen, about Yugoslavia and about life in general.

JC: When did you first read Black Lamb and Grey Falcon? What was your reaction?

PT: I was traversing the shores of the Mediterranean for my book The Pillars of Hercules—around 1994—and began to read it, with enormous pleasure, because the Dalmatian coast was on my route. It is not a book that one can read straight through, but rather a journey you need to take with rest-stops; it helps if you know a little bit about Yugoslavia, but even if you don’t you can thrill to Rebecca West’s asides. By the way, in her seventies she traveled in Mexico-her Survivors in Mexico was published posthumously.

Henry David Thoreau, The Maine Woods

Three enlightening trips to the wilderness by a shy but not timid traveler written around the same time he was in his Walden cabin.

JC: As you point out in Figures in a Landscape, Thoreau’s three Maine trips, from 1846 to 1857, overlap with the publication of Melville’s greatest works. You note that in a discarded section of Ktaadn, the first of these trips, that Thoreau “argued that he experienced deeper wilderness in Maine than Melville had as a castaway in the high volcanic archipelago of the remote Marquesas,” indicating Thoreau was familiar with Typee and competitive with Melville. At this point in your lifetime as a traveler and a travel writer, would you agree with Thoreau? Or Melville?

PT: Thoreau died in his forties, Melville lived much longer. More to the point, Thoreau lived with his mother the whole of his life—and I think he greatly envied Melville’s health and boldness and literary popularity for Typee. Thoreau was a Harvard classmate of Richard Henry Dana and was probably conflicted about the success of this young man’s Two Years Before the Mast (see below). Yet anyone who wishes to learn how to observe and write about the natural world, and who wonders about the human condition and what really matters on earth, will be greatly enlightened by The Maine Woods and Walden.

Richard Henry Dana, Two Years Before the Mast

An experience that changed Dana’s life, around the Horn to Spanish California. Life altering for the reader too. Adventure and injustice on the high seas.

JC: Richard Henry Dana was, like you, a New England native who journeyed forth and changed literature. He clearly influenced Melville. What makes his memoir of daily details of what was in his time a relatively common journey so compelling? I remember how emotional he was at points in the book, as in when a mate fell overboard. “A man dies on shore-you follow his body to the grave, and a stone marks the spot… but at sea, the man is near you-at your side-you hear his voice, and in an instant he is gone, and nothing but a vacancy shows his loss.” Does this aspect of the book help elevate it beyond sheer reportage?

PT: The whole book is elevated beyond reportage. Here is a fairly wealthy but very young man (like Cherry above) who joins a voyage and lives in a cramped cabin “before the mast” in the bow of the ship-around the Horn to California and back, under the command of a wicked captain. It was life-altering for him and makes a strong impression on the reader, for the elegant bit you quote and for a terrifying episode where an innocent man is flogged half to death on board. Seeing this injustice, Dana resolved to return home and study law and later he became active in the Abolitionist movement.